Norse

Giants in Norse Mythology

Giants in Norse Mythology

Giants play a major role in Norse mythology, but what exactly that role is might not always be clear. Keep reading to learn about the many different ways the Norse people viewed the race of giants!

In English, the word “giant” brings up a very clear image. The giants are larger than humans and usually violent, brutish, and unintelligent creatures.

This view is largely influenced by Norse and Germanic mythology. The brutish giants who fought the noble Aesir gods were the fur-clad barbarians of the mountains that we often think of today.

This view, however, is not necessarily how the Norse people themselves would have seen the giants.

The word “giant” is used rather liberally in English translations to describe the jotnar, one of the many mythological races of the Norse legends. The jotnar, however, were as varied in form and temperament as the human race, if not more so.

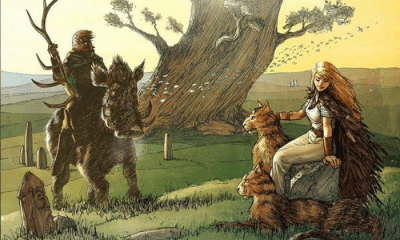

While some Norse giants were strong, brutish, and greedy, others were great friends of the gods. They could be beautiful and noble as often as they could be churlish and cruel.

Some jotnar were elemental monsters who were set on the destruction of the world. Others, however, were queens and goddesses known for their grace and good natures.

Who were the Norse giants and why are they now thought of as enormous brutes?

Defining the Giants

Modern translations of Norse mythology often mention the giants. Whether as allies of the gods or as mortal enemies, they feature heavily in the written works of Norse poets.

In fact, the giants are one of the most often-mentioned races in all of Norse mythology. Along with the gods and humans, they appear in nearly all of the surviving stories.

The Norse giants, however, were likely seen much differently than they are by modern readers.

The Old Norse word, jotunn, does not directly translate into English. The closest cognate, giant, is based on Greco-Roman mythology and has a different meaning than the Norse term would have.

The jotnar, for example, were never described as particularly large. While modern English speakers almost invariably equate the word “giant” with size, it did not have that connotation in the Norse world.

The Norse giants were also not always known for extreme strength or brutality. While some displayed these characteristics, others were described as extremely beautiful, wealthy, or skilled in magic.

Contrary to popular belief, the jotnar were also not all enemies of the gods and men. Some were viewed negatively, but others were allies or even spouses of the gods.

The jotnar in Norse mythology seem to defy a simple translation. Broadly speaking, they can be divided into three different categories.

The first, and the most familiar to many modern readers, were the most similar to how giants are often seen today. They were brutish and brutal, often positioning themselves as hateful to the gods and men.

The second group of giants were the opposite. They were friends of the gods, helpful to people, and were shown as civilized and intelligent.

While these two groups were opposites in their behavior, they were virtually indistinguishable from most gods and men. Like humans, they had varied personalities and behaviors even within the same family.

The third type, however, was very different.

Some jotnar were linked to an elemental power. Giants of fire and frost were universally antagonistic creatures who represented the force of a primordial element.

In each story, therefore, the word “giant” can refer to a different type of being. While some were more like trolls, and were even called by that word in some texts, others were nearly the same as the gods.

Ymir and the First Jotnar

All types of jotnar, however, were said to have the same ancestor.

Ymir, the first giant, emerged in the empty void of Ginnungagap at the beginning of time. When the heat of Muspelheim and the frost of Niflheim combined, they created a thick mist that eventually took a human-like shape.

Muspelheim’s heat also made Ymir sweat. The first frost giants were born from the beads of sweat that dripped off his body.

According to legend, these early jotnar were cruel and destructive. When the first gods were born, Ymir and his children treated them horribly.

Eventually, Odin and his brothers decided to kill Ymir. When they did, the torrents of blood that flowed out of his body drowned most of the wicked frost giants he had spawned.

While later jotnar were not noted for exceptional size, Ymir was truly gigantic. He was so large that the gods were able to use his body to create the entire world.

His skull became the dome of the sky. His brains and eyes were kept in it as clouds, the sun, and the moon.

His blood was gathered back up and used to make the seas, lakes, and rivers. His flesh was the earth, with bones and teeth spread across it to create mountains and fjords.

Even Ymir’s eyelashes were used. They created a wall around the world of men to enclose it and keep it safe from the surviving frost giants.

These giants were said to be the ancestors of all the giants that followed them. Like mankind, they eventually formed different groups.

The elemental giants, who more most likely the closest relatives to Ymir, were largely contained in the worlds that had created them. More human-like jotnar, however, had much more varied lives.

The Giants as Enemies

Many of the jotnar appeared in later myths as enemies, or at least annoyances, of the gods.

In one of the earliest examples, a giant attempted to defraud the gods by disguising himself as a common mason to rebuilt the walls of Asgard. He nearly won Freya’s hand as his pay when his superhuman strength allowed him to complete the work faster than a man ever could.

Another famous enemy of the gods is Thiazi, the crazed giant who demanded marriage to Idunn in exchange for Loki’s freedom. Loki delivered the goddess of youth, but the gods commanded him to rescue her and Thiazi was killed while pursuing them.

In another story, a giant steals Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir, and demands marriage to Freya as a ransom. He and his entire court are killed when Thor and Loki disguise themselves as women to gain entry to his hall.

Many stories mention fights between the gods and the jotnar as common occurrences without such elaborate tricks and plots.

After giving away his sword, Freyr faces off against a giant named Beli. Little is said about the fight other than the fact that Freyr had to use a deer’s antler as a weapon.

While these giants were hostile toward the gods, they were not entirely dissimilar to them. They had human traits such as greed, madness, or lust that made them dangerous.

The same was not true of the giants that would reappear at Ragnarok.

In the midst of this clash and din the heavens are rent in twain, and the sons of Muspel come riding through the opening. Surt rides first, and before him and after him flames burning fire. He has a very good sword, which shines brighter than the sun. As they ride over Bifrost it breaks to pieces, as has before been stated. The sons of Muspel direct their course to the plain which is called Vigrid … To this place have also come Loke and Hrym, and with him all the frost-giants. In Loke’s company are all the friends of Hel. The sons of Muspel have there effulgent bands alone by themselves.

-Snorri Sturluson, Prose Edda, Gylfaginning (trans. Anderson)

The “sons of Muspel” are usually described as fire giants from the realm of Muspelheim. The frost giants, the same type that is associated with Ymir, come with Loki likely from Niflheim.

These giants are much more fearsome enemies than the common types the gods encounter in other myths.

Historians have a variety of interpretations for why the different types of jotnar are shown in such radically different ways.

Many believe that the fire giants in particular are later additions to the story. They were inspired by Christian and Greco-Roman motifs of giants and demons and added into the story of Ragnarok after Christianity became popular.

Even if the elemental giants were an original feature of the story, they were not the most powerful and dangerous jotnar the gods would face. A far greater threat would be posed by the giant that was once counted as one of the gods’ friends.

Loki, the trickster, was not one of the Aesir or Vanir gods. He was a jotunn who originally positioned himself as an ally of Odin and his people.

Eventually, however, Loki turned on the gods and became their most hateful enemy. He and hs children would be the primary enemies of Ragnarok.

Loki’s children show another notable feature of the jotnar in Norse mythology; not all had the appearance of humanity.

Both Loki and his mistress, Angrboda, were jotnar. Their children, while technically members of this race, were monsters.

Fenrir was an enormous wolf while Jormungandr was a serpent large enough to encircle the world. From the waste up, Hel appeared to be a beautiful jotunn maiden, but her lower half was that of a decaying corpse.

The children of Loki showed that the jotnar could take unexpected forms and be the parents of entirely inhuman creatures. While only one of Angrboda’s children even remotely resembled a human form, all were technically giants.

Intermarriage with the Gods

Some of the gods’ giant enemies showed another way in which the jotnar were a diverse race. Several were closely-related to giants who became close allies of the gods.

Many of these were female jotnar who intermarried with the Aesir and Vanir gods. The women of the different mythological races showed just how thin the line was between the gods and their possible enemies.

While the gods were easily separated into the Aesir and Vanir groups, the goddesses were more varied. The word for the goddesses, asynjur, applied to female jotnar and elves as well.

Many of the gods married giantesses. Even if their relatives were enemies, these women were almost universally described as beautiful, graceful, and noble.

Giantesses among the gods included:

- Skadi: Perhaps the most famous giantess to marry a god, she was the daughter of the villainous Thiazi. Although her marriage to Njord, arranged in repayment for her father’s death, was not entirely happy she was still an honored goddess and described positively.

- The mothers of Heimdall: The god who watched the Bifrost was said to have been born to nine maiden sisters. Although he was named as an Aesir, his mothers were jotnar.

- Gerd: Freyr’s wife was a jotunn. She was so radiantly beautiful that he fell in love the moment he saw her.

- Jarnsaxa: One oft he daughters of Aegir and Ran, she was also the mother of Thor’s son Magni.

- Bestla: Although not called a giantess, Odin’s mother is often believed to have one of the early jotnar born to Ymir.

- Grid: The mother of Odin’s son Vidarr, she also gave Thor advice on how to beat another giant, Geirrod, in battle and lent him magical items for the fight.

- Rindr: Described as either a giantess or a human princess, she was the mother of Odin’s son Vali.

- Gunnlod: When her father obtained the Mead of Poetry, Odin seduced her to steal it back.

- Hrod: Although both she and her husband were giants, their son Tyr was a god of the Aesir.

- Jord: The personification of the earth and possible mother of Thor was sometimes named as a giantess.

- Sigyn: Loki’s wife was seen as a paradigm of devotion and selflessness. Although her husband became a more negative figure, Sigyn was viewed as a virtuous goddess.

In addition to the giantesses who were wives, mistresses, and mothers of the gods, several male jotnar were closely allied with the Aesir as well.

Some were so closely linked to the gods that they were often thought of as deities themselves.

Aesir and his wife Ran, for example, were a giant couple who lived in a magnificent undersea palace where they hosted the gods for feasts. Although they were giants, they are often described as the god and goddess of the sea and have attributes similar to the Aesir or Vanir.

Mimir, the god of memory and knowledge, is also often called a jotunn in some sources. If he was a child of giants, he was so closely linked to the Aesir that he was one of their representatives to the Vanir after the war.

Odr, described in some sources as Freya’s husband, is named as a jotunn by some writers.

Many recognized gods are considered members of the Aesir pantheon even when their parents were jotnar. At least one sources claims that Tyr’s parents were giants, for example.

When a jotunn and god intermarried, their children were also almost always counted among the gods. Most of Odin’s sons, for example, had a giantess mother.

In sagas, the same held true for humans. Several kings were said to have married giantesses, but their sons were fully human.

The jotnar seem, therefore, to have been so closely related to the gods that they were indistinguishable. Not only was intermarriage common, but the giants who were allied with the gods were just as powerful and renowned as many of their divine counterparts.

The Land of the Giants

Not all the giants lived among the gods or in a primordial realm, however.

While a definitive list of the worlds in Norse cosmology is difficult to compile, virtually all sources agree that the giants had a world of their own. This was Jotunheim.

Compared to many other realms, Jotunheim is mentioned fairly often in surviving myths. The gods travel there on many errands, although it is usually noted to be a dangerous place for them to travel freely because many of its residents are hostile.

Thiazi, for example, took Loki hostage when the trickster was in Jotenheim.

The world of the giants was usually described in terms that would be very familiar to most Scandinavian readers.

The connected stories of Thiazi and Skadi portray Jotenheim as a mountainous world with heavy snowfall and thick forests. It was not altogether dissimilar to parts of Sweden and Norway.

Jotenheim was not entirely rugged, however. Many of the giants had great wealth and lived in lavish halls that rivaled those of the most wealthy human kings.

Like Asgard, Jotenheim appeared to be very similar to the world of men. The major difference was in its residents.

In fact, some stories implied that Jotenheim and Midgard were mot as widely separated as they are sometimes portrayed.

In various legends, giants and humans come into relatively frequent contact. Kings and heroes marry giant women or fight more brutish jotnar in the mountains.

This would not be likely if the worlds of the two races were far apart. Unlike Asgard, Jotenheim did not have a bridge linking it directly to the world of men.

Some scholars point to details in the story to theorize that Joteinheim and Midgard may have actually existed side by side.

People and gods are often said to travel relatively short distances to encounter the jotnar. They are sometimes described as living in the north rather than on an entirely different world.

Midgard’s enclosing wall also implies that the giants may have been near neighbors.

The wall that was made from Ymir’s eyebrows is often compared to the walls that would enclose a farmyard or village in the Viking Age. It denoted a safe space that separated humans from the dangers of the wild.

If Midgard was a town on a large scale with a protective wall, some historians believe the Jotenheim was the world outside its borders. Rather than being an entirely separate world, it was the wild land that surrounded the safer world of men.

This would explain not only why humans came into such close contact with the giants, but also why the wall needed to be built in the first place. It did not protect Midgard from a distant threat, but from the hostile giants that were right outside of it.

How the Image Changed

Giants were not a single, monolithic race of evil beings in Norse mythology. Yet, this is how they are often portrayed today.

The changing view of the giants was influenced by many changes in European society throughout the Middle Ages.

Norse literature generally depicted the jotnar as capable of both good or evil, just like the human race, but a more absolutist view emerged.

In folklore, stories of wicked and threatening giants remained popular. The more amicable jotnar were largely ignored, however.

This was in part because Christianity replaced the pagan gods. Giants like Aegir that were seen as almost god-like themselves were displaced by the new religion.

In translation, the jotnar were also changed. Friendly individuals were more likely to be called gods, while the more villainous characters were called giants or trolls.

The view of giants was also due to an increased influence from Greek and Roman cultures.

The Christian Church of the Middle Ages used Latin in its liturgy and the language of Rome remained the written language of law, scholarship, and international communication for many centuries.

While the Church itself did not promote the pagan gods of Rome, they were a part of the culture that was brought in. Greco-Roman myths were familiar to many of the men who wrote down the Norse legends because they had been educated in the Latin language.

They equated the jotnar with similar figures in Roman and Greek mythology. The Titans and Gigantes were powerful enemies of the gods.

This is likely where the association with enormity comes from. While some linguists draw ties between terms for the jotnar and words for mass, the Greek Gigantes were likely the inspiration for the larger than life giants in Norse mythology.

Christianity itself also influenced the view of the jotnar. Medieval Christianity drew much clearer lines between good and evil than Norse tradition did, and was quick to position a non-human race as related to the demons they believed in.

The Many Different Norse Giants

The English word “giant” is often used as a translation for the jotunn, a mythological race in Norse legends. The jotnar, however, were not entirely like the English definition of a giant.

While they were not gods or men, the jotnar were often mistaken for either.

The Norse giants did not stand out because of their enormous size or misshapen features. While some were unattractive, even entirely inhuman, others were exceptionally beautiful.

Giants could be brutal enemies of the gods. They could also marry into the pantheon, be close friends of the Aesir, or even be popular enough to be considered gods in their own right.

The line between friend and enemy could even be blurred. The most famous jotunn in Norse mythology, the trickster Loki, was a one-time friend of the gods who became their greatest enemy.