Norse

Hel: The Norse Goddess of Death and Her Realm

Hel: The Norse Goddess of Death and Her Realm

In Norse mythology, Hel was the ruler of the land of the dead. How much do we really know about Hel and her realm, though?

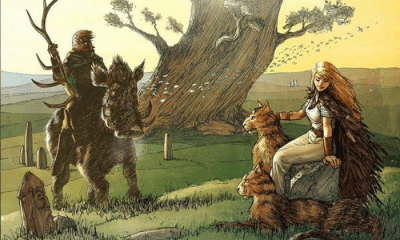

Of Loki’s three monstrous children, many people find Hel the most sympathetic.

While her brothers were violent monsters, she was the most human in appearance. While later made more macabre, her only original connection to death was a blue pallor and dour expression.

Hel’s relatively unthreatening nature is likely why she was not punished as harshly as her family members. While her father and brothers were all bound, Hel was sent to a far-off realm to be a ruler.

Hel’s domain was the grim, frozen land of death. She and her world were interchangeable in both name and characterization.

Hel’s realm plays an important role in many of Norse mythology’s most well-known stories. From the first prophecy of Ragnarok to the battle’s brutal climax, Hel is at the center of events.

Some historians, however, think that this wasn’t always the case. Hel, both the goddess and the place, show that in studying Norse mythology it is often hard to separate ancient beliefs from later literature.

Hel and Her Family

In Norse mythology, Hel was one of the three monstrous children of Loki and his mistress, Angrboda.

Loki and Angrboda kept the existence of their children from the gods for some time, but when the Aesir learned that they had been born they were greatly concerned.

Prophecies of doom had been connected to Loki’s offspring. Although Angrboda is not characterized in detail, the Prose Edda also suggests that her involvement was alarming to the gods.

Determined to reduce the risk posed by Loki’s children, the gods immediately decided to take them from Jotenheim and put them in a safer place.

Jormungandr, the serpent, had not yet reached his full size. He was thrown into the sea easily, although he would eventually grow large enough to encircle the world.

The gods tried for a time to tame the wolf Fenrir. When he grew too large and vicious to trust, however, Tyr sacrificed his hand to have him bound with unbreakable chains.

Of the three, Hel was the most human in appearance. The gods immediately noticed, however, that she was no ordinary giantess.

While later art often showed her as decaying and grotesque, the Poetic Edda claims that her appearance more subtly hinted at her connection to death. She was a slight blue-gray color and had a gloomy, downcast face even as a child.

Although she was one of Loki’s monsters, she did not represent the same immediate physical threat as her bestial brothers. Odin decided that Hel would be banished but not placed in chains.

Hel was sent far from Asgard and Midgard, to a place that was almost impossible to reach. She was given dominion over the dead.

While Loki had hidden the births of his children from the gods, he was not immediately punished. Although the prophecies of Ragnarok centered largely on his actions, Loki would remain free until after the death of Baldur.

The Realm of Ice and Death

Hel’s realm of death was called by many names.

It was usually believed to have been in the world of Niflheim. The specific home of the dead in this primordial world of frost and mist was called Niflhel.

Sometimes it was known as Helheim, or “Hel’s Home.” Occasionally, her hall is specifically referenced as Eljudnir.

Most often, however, Hel’s realm is simply called Hel as well. Like the Greek Hades, the ruler of the dead was synonymous with the land she ruled.

Hel was not bound in the same way as Fenrir and Loki would later be, but her world was a prison nonetheless. Her home was said to lie beneath one of Yggdrasil’s great branches, which kept her and the denizens of her world from traveling freely.

Hel’s realm was not the only potential afterlife the Norse people believed in.

While the view of the afterlife changed over time, most Norse people believed that the manner of a person’s death determined where they went afterward.

The most valiant warriors who died in battle were selected to go do Odin’s hall of Valhalla or to be with Freya in Folkvangr. Eventually, Folkvangr was also believed to house those who died well but not in battle, such as women who lost their lives in childbirth.

People who were lost at sea were dragged in nets down to Aegir’s underwater palace. They joined the treasures of shipwrecks at the bottom of the ocean.

Most people, however, died in a less glorious way. They found themselves in Hel after succumbing to illness, old age, misfortune, or hunger.

Snorri Sturluson later amended the view of Hel. Influenced by medieval Christian notions of reward and punishment in the afterlife, he saw Hel as the place where those who committed terrible crimes were sent.

Through most of Norse history, however, people thought they were likely to enter Hel’s home after death. The prospect was not inviting.

Lying within Niflheim, Hel was a place of perpetual cold, fog, and darkness. Although it was not intended for punishment, it was a joyless and dreary place.

Hel was not unkind to her people, however. The Prose Edda claimed that she could give lodging and gifts to those who died of old age and disease, providing them some small comfort in her unhappy world.

Hel’s Wager

Humans were not the only ones who ended up in Hel’s realm.

In one of Norse mythology’s most well-known tales, the god Baldur was killed when Loki tricked his blind brother into hitting him with a weapon made of mistletoe, the only thing in the world that could harm him.

The gods were all heartbroken at Baldur’s death. They arranged a grand funeral where every member of the Aesir and Vanir came together to mourn.

Baldur’s wife, Nanna, was hurt so terribly by the loss that she died of grief as the funeral began. Her body was added to the funeral pyre of her husband so they could journey to Hel together.

Baldur’s mother, Frigg, had attempted to ensure his protection by making everything in all the Nine Worlds swear to do him no harm. Although she had overlooked the mistletoe, she was still determined to protect her son.

She asked the gods for a volunteer to undertake the long and difficult journey to Hel. She hoped that their pain would move Hel to pity and Baldur would be released back into the world of the living.

Hermod volunteered. Odin lent him Sleipnir, his swift horse that could travel between the realms.

Even on Sleipnir, the journey took nine nights. Hermod rode in total darkness until he reached a bridge near Niflheim’s edge.

Continuing downward, he came to the closed gates of Hel. Sleipnir easily jumped over them, allowing Hermod to enter the realm even though he was still alive.

Inside, he found Baldur seated in a position of honor. He talked with him through the night.

In the morning he asked Hel whether Balder might ride home with him, and told how great weeping there was among the asas. But Hel replied that it should now be tried whether Balder was so much beloved as was said. If all things, said she, both quick and dead, will weep for him, then he shall go back to the asas, but if anything refuses to shed tears, then he shall remain with Hel. Hermod arose, and Balder accompanied him out of the hall. He took the ring Draupner and sent it as a keepsake to Odin. Nanna sent Frigg a kerchief and other gifts, and to Fulla she sent a ring. Thereupon Hermod rode back and came to Asgard, where he reported the tidings he had seen and heard.

-Snorri Sturluson, Prose Edda, Gylfaginning (trans. Anderson)

When Hermod returned, the gods immediately spread out through the Nine Worlds asking every creature they saw to cry over Baldur’s death. Without fail, every one of them did; even rocks and mountains wept when they learned that Baldur could be lost forever.

They were nearly done when they met an old giantess living in an isolated region of Jotenheim. When they asked her to cry, Thokk replied that she had no love for Odin’s son and would let Hel keep him.

Thokk’s refusal to mourn meant that Baldur was consigned to Hel for good. The gods would continue to mourn his loss.

Sturluson notes, however, that Thokk was likely not what she seemed. Most people believed that the surly giantess was Loki in disguise, ensuring that Baldur would not be able to be brought back to life.

The Residents of Helheim

Baldur was not the only notable resident of Hel’s world.

While Hel was, expectedly, not as busy or frequently visited as most other worlds, it was not entirely devoid of life. The land of death had some of the same features as any other place.

There were some creatures that had been consigned to Hel despite not being dead themselves. Othe residents were among the dead, but still played a role in certain myths and legends.

These included:

- The Volva: Odin traveled to Hel before Baldur’s death to speak to a long-dead volva, or seeress. He used a spell to revive her and received the prophecies of Ragnarok.

- Ganglati and Ganglot: In the Prose Edda, it is sad that Hel has a servant and a slave to wait on her in her hall. Whether they are living or dead is not made clear. Both their names refer to laziness.

- The Cock: The volva tells Odin that three cocks will crow in different worlds when Ragnarok begins. One of them, the only one that is not named, is a “sooty-red” bird from the halls of Hel.

- Garm: One of Hel’s most well-known denizens is its guard dog. Chained in a cave at Hel’s gate, Gar will break loose at Ragnarok.

- Modgud: Although she does not live within Hel’s borders, Modgud is only mentioned in relation to the journey there. She guards the bridge that Hermod crosses as he approaches Helheim and tells him where to go and who has passed recently.

- Nidhogg: The serpent chews on both the corpses of the dead and the roots of Yggdrasil, spreading decay into the tree. He is one of the many monsters who will be released at Ragnarok.

It is noteworthy that most of the beings described in Hel are connected in some way to Ragnarok.

When the volva gives Odin her prophesy, she says that Hel will have an important part to play. She may be referring either to the goddess of the realm or to the place itself, since both figure into the final story.

The named figures in Hel are also connected to Ragnarok because most of them appear in Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda. Much of his work is directly tied to the events leading up to the battle, and more than any other Norse writer he made use of foreshadowing in telling his story.

The Invasion of Hel

As the seeress told Odin, Hel would play a major role in the events of Ragnarok.

While Snorri Sturluson’s account adds many more enemies, Loki and his children were traditionally at the heart of the Ragnarok story. They would be the chief enemies of the gods who, with some allies, would destroy both the world of men and the society of the gods.

Loki and all three of his children would break free of the punishments set on them by the gods when Ragnarok began.

Fenrir would break his chains, Jormungandr would haul himself back up onto the land, and Hel would march out of Niflheim.

With her, she would bring all the dead who had been sent to her. Over the course of history, she would collect a massive army of bodies from the Nine Worlds that Odin had made her the goddess of.

She would be accompanied by the monsters that had been imprisoned with her. Garm and Nidhogg would both be freed, as would the frost giants who still lived in the cold land of Niflheim.

Descriptions of their invasion would imply that Loki would be with his daughter’s army at this time.

He would arrive at the site of the battle at the prow of Naglfar, a ship made entirely from the finger and toe nails of the dead. His crew would be made up of Hel’s people, the dead, and giants.

Despite the prominent role her realm and its denizens would play in Ragnarok, Hel’s own place in the battle is never mentioned.

Like the goddesses of the Aesir and Vanir, Hel does not seem to take part in the battle herself.

Although her family and her army of the dead will be destroyed, it is, therefore, possible that Hel would survive Ragnarok.

The Prose Edda, which includes a description of the world being remade after the battle, says that new, more pleasant, realms will be made for the dead of Ragnarok and its aftermath. Although she is not named, it is possible that Hel would continue her role as the ruler of one or more of these future afterlife worlds.

Invention or Tradition?

Scholars have long been divided on what to make of Norse mythology’s description of Hel and her realm.

Although she is often described as the goddess of death, many historians are uncertain as to whether Hel is best categorized as a deity or a monster.

One deciding factor would be whether the people of the time had any type of cult or ritual worship associated with her. If people offered prayers and sacrifices to Hel, she was likely seen as a goddess.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to know whether this happened because of a scarcity of information. Because rituals were not written about and archaeological evidence is scarce and unclear, how the Norse people viewed Hel cannot be known for sure.

Some writers have suggested that based on her characterization and associations, it seems unlikely that Hel would have been seen as a goddess. Others, however, use comparative religion to disprove this assertion.

Similar death goddesses in other Indo-European cultures were seen as threatening figures but still received veneration. From the Irish Badb to the Hindu goddess Kali, death goddesses are known outside of the Norse tradition.

Just as difficult is determining how much of the view of Hel’s realm we have today would have been shared by Viking Age Scandinavian people.

The most detailed descriptions of Helheim come from the Prose Edda, which was not written until the early 13th century. While Snorri Sturluson still wrote in Old Norse and demonstrated a familiarity with earlier known works, his writings betray later influences.

It is widely believed that many of Sturluson’s views on Hel were influenced by Christian thought. While Iceland was not entirely Christianized even in the 13th century, as the dominant religion it could not entirely be ignored.

Much of the Prose Edda is framed in such a way as to make it more palatable to Christian readers, and less offensive to the Church. Descriptions of Hel as a place of punishment and of its ruler’s acts of kindness toward those who died of illness may betray the influence of Christian views.

Some have even questioned whether Snorri Sturluson invented the character of Hel entirely.

The writer is believed to have created many of the other characters in his versions of the myths, including Garm and the fire giants. While Hel may have been occasionally thought of as a personification, some people believe Sturluson invented the character for his work.

Earlier sources often refer to the realm of Hel, but rarely if ever talk about an associated ruler. The first clear attestations to a goddess of Hel are from the 10th and 11th centuries.

Some historians believe that Hel was originally thought of as the grave rather than any fully realized Underworld. When Odin travels to meet the volva, for example, he has to revive her in order to communicate.

As Norse belief was more influenced by traditions from elsewhere in Europe, the idea of an afterlife emerged. The gloomy, grim land of Hel is similar to the misty realm of Hades in Greek mythology.

Parallels can also be seen between Hermod’s journey and the legend of Orpheus. Both journeyed to the Underworld to bring back a loved one, a task that failed at the last minute.

Hel further developed as Christian influence became more prominent. A previously unknown moral component was added.

If Hel survived Ragnarok, she also would become the goddess of an afterlife that was even more influenced by Christian ideas. The pleasant rebirth that ended Sturluson’s account was likely rooted in Christian stories of Paradise rather than a native Norse belief in happy endings.

Because the historical record is incomplete, it may never be known whether Hel was an ancient example of the death goddess archetype, a later personification of the grave, or from another source altogether. She and her realm remain, however, a compelling part of the complex beliefs of the Norse people.

Belief in Hel

Based largely o a few sources, Hel is known as the Norse goddess of death. She ruled over a realm that shared her name.

One of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, Hel was banished when the gods discovered the threat she and her siblings represented. While her brothers were chained, she was made the ruler of the world of the dead.

Usually said to be in the icy world of Niflheim, Hel’s realm was a dark and dreary place. Other than the dead, it was inhabited only by Hel herself and a handful of bound monsters.

Many famous myths involved travel to Hel’s world, however. Odin went there to consult a volva and Hermod tried to bargain with the goddess after Baldur’s untimely death.

Most of these stories in some way related to the events of Ragnarok. While Hel did not seem to take part in the fighting herself, her father Loki led the masses of the dead and the monsters of Niflheim against the gods.

Some historians believe that parts of the story, perhaps even the existence of Hel as a character, were later additions to Norse lore. Influences from both Greco-Roman and Christian beliefs led to the afterlife being seen as a physical realm with a deity at its head.

Others, however, see similarities to death goddesses from other cultures. They believe Hel was a threatening but revered goddess in the same tradition.

Because both the written and archaeological records are incomplete, we may never be able to say for sure whether Hel was an ancient goddess of the Norse people or an invention of medieval literature.