Norse

Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd

Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd

What was the relationship between the great World Tree and the Well of Fate? Keep reading to find out!

Many Germanic cultures expressed the idea that the world was supported by a World Tree. In Norse mythology, this tree was called Yggdrasil.

Yggdrasil not only supported the Nine Worlds of Norse cosmology. It also provided a sacred conduit between them, allowing communication on a grand scale between men, the gods, and the dead.

Yggdrasil was not self-supporting, however. It was fed by three wells, each of which had its own powers. The most famous of these, the Well of Urd, was where the Norns measured and wove the fates of every living thing in the Nine Worlds.

The Well of Urd did more than just give water to the World Tree, however. It also affected the fate of the tree and mankind by keeping Yggdrasil healthy, for a time, in spite of the forces that constantly weakened it.

The World Tree Yggdrasil

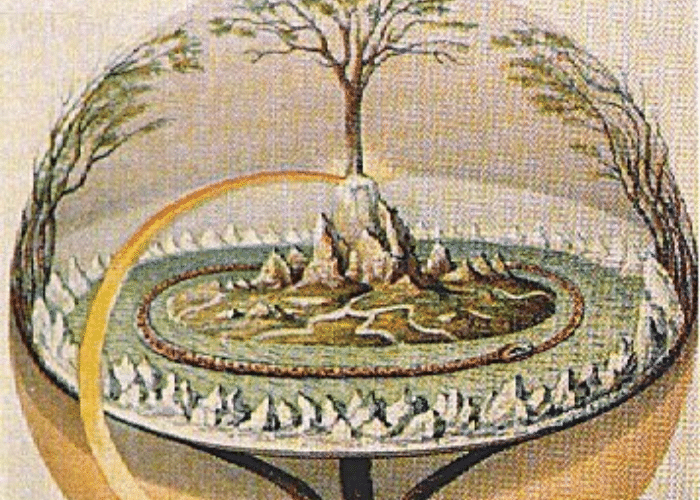

According to Norse cosmology, the World Tree was the center of all creation.

Although the exact layout of the cosmology was open to interpretation, the Nine Worlds were said to either lay along the trunk of Yggdrasil or within its branches.

Norse artwork does not illustrate the cosmology of the Nine Worlds. While Yggdrasil is commonly shown, only the tree is pictured, not the worlds that were said to exist on it.

Some stories, in fact, seem to imply that Yggdrasil did not exist outside of the Worlds at all. One poem says that the tree is “under the earth,” implying that it grew either within or beneath Midgard, the realm of men.

Generally, however, Yggdrasil is pictured as supporting the Nine Worlds.

There is also uncertainty as to the age of Yggdrasil.

Most accounts imply that Yggdrasil existed before any of the Nine Worlds or any other form of life. Ginnungagap, the empty space that would later be filled by those worlds, is often described as the length of Yggdrasil.

A few sources, however, discuss a world before Yggdrasil or its growth from a seedling.

Norse writers did not seem to give much detail about Yggdrasil itself, possibly because the World Tree was a well-known and broadly-understood archetype. The World Tree was so prevalent in mythology that many Germanic tribes believed it was mirrored in the living world, as well.

Life in the Tree

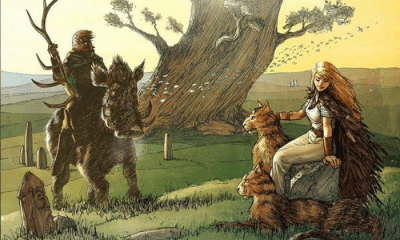

While most life existed in the Nine Worlds, with each being the home to one of the intelligent races of Norse mythology, Yggdrasil itself was home to its own ecosystem.

A giant eagle perched in the uppermost branches of Yggdrasil. A smaller hawk set on its head, between its eyes.

While the eagle was not named, the Prose Edda called the hawk Vedrfolnir, or “Wind Bleached.”

The image of the hawk and the eagle is unique to Norse cosmology. Contemporary sources give no explanation for the unusual image or two birds of prey living one on top of the other.

Some scholars have suggested that Vedrfolnir served a similar purpose as Odin’s ravens, flying between the worlds to bring back news and information. The eagle may represent Odin himself, as it is a common symbol of kingship and a form often taken when the gods shapeshift.

In Niflheim, the world of primordial ice, a serpent named Nidhogg lived on one of the World Tree’s roots. It was implied that the root trapped him in or near Niflheim but that he would escape at Ragnarok.

Nidhogg and the eagle were sworn enemies. The serpent could not travel up to attack the eagle, however, and the unnamed bird never left his perch on top of the tree.

Instead, the two used a squirred called Ratatosk to exchange insults. The squirrel constantly ran back and forth repeating the messages of hatred passed between the bird and the snake.

While some possible symbolism has been proposed for Ratatosk, many historians believe that the squirrel was a creative embellishment to the imagery of the World Tree. Possibly inspired by little more than the chattering, scolding noises made by common tree squirrels it was an addition to the story that did not have a deeper meaning.

Ratatosk’s name may support this idea. While it could mean “Travelling Tusk,” or be an Old English loanword for “Rat Tooth,” it also mimics the sounds made by squirrels themselves.

Four stags and harts also lived within Yggdrasil’s branches. Dainn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr, and Duraþror craned their necks to reach higher branches and feed on the World Tree’s leaves.

Various explanations have been given for the four deer that chew on Yggdrasil’s foliage. Scholars have likened them to the four seasons, the directional winds, the elements, or the stages of the moon and the passage of time.

Norse legends predicted that in the future, Yggdrasil would also be a temporary home for two humans. After Ragnarok, it was said, a couple named Lif and Lifþrasir, “Life” and “Lover of Life,” would survive and take refuge in Yggdrasil’s branches.

When the world was destroyed they would remain hidden in Yggdrasil and survive off its leaves. As new land emerged on Midgard, however, they would leave the tree’s protection and return to populate the newly remade world.

Yggdrasil as a Sacred Tree

Yggdrasil’s primary function in mythology was not as a support for the Nine Worlds, but as the ultimate expression of the sacred tree.

Sacred trees were a central aspect of ancient Germanic religion. Both contemporary accounts and archaeological evidence show the importance of these trees in ancient European cultures.

These sacred trees were thought to connect the worlds of men, gods, and the dead. As such, they were important sites for both prayer and remembrance.

In Norway, for example, a birch tree planted on top of a Norse-era burial mound was the site of veneration as late as the 19th century. Ale was poured on its roots, likely a continuation of ancient traditions of offering libations to the dead.

In the 11th century, Adam of Bremen described a massive tree growing next to the Temple of Uppsala in Sweden. He claimed that no one could identify the tree’s type but that it miraculously stayed green in all seasons.

Some of the most convincing evidence for sacred trees, however, comes from the people who did not believe in the ancient gods of Germany.

Throughout the Middle Ages, records exist of trees and groves being singled out for destruction by Christian rulers and missionaries. Many accounts describe these trees as sites of pagan worship or the homes of demons that people were willing to fight, or even die, in defense of.

A sacred oak, for example, was purportedly cut down near Hesse, Germany by Saint Boniface when he proselytized to the people there. People were supposedly converted by the miraculous destruction of the oak and its wood was used to build the area’s first Christian church.

Norse mythology gives some insight into what type of rituals may have occurred at these sacred trees.

In one of the most well-known stories that take place in Yggdrasil’s branches, Norse legends make it clear that such trees were the sights of sacrifices to the gods.

In the Poetic Edda, Odin describes his own sacrifice on Yggdrasil. To gain knowledge of the runes and their magic, the chief of the gods offered himself as a human sacrifice.

I know that I hung on a windy tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.

-Poetic Edda, Hávamál (trans Larrington)

This poem gives some of the best information available on how sacrifices were likely conducted at sacred trees. Men and animals alike were hanged, often after being stabbed or otherwise injured, for long periods of time.

Yggdrasil was a sacred tree on a large scale, serving the same purpose in mythology as the trees and groves of Europe served to pre-Christian Germanic worshippers.

While the people of Europe used trees to communicate personal messages and offer personal sacrifices between worlds, Yggdrasil allowed these same uses to be carried out by the gods.

The Aesir could use Yggdrasil to convey messages of far greeted importance. Like humans, they met at the base of the tree to discuss the events of their world, but these events were of cosmic rather than local importance.

And while individuals and communities could offer sacrifices to Odin and the other gods at their sacred trees, Yggdrasil served as the tree that allowed Odin to offer the greatest sacrifice of all, himself.

The Wells of the Roots

Like many aspects of Yggdrasil and the Nine Worlds, the wells that fed the World Tree were given various names, locations, and functions.

The three sources of water named for Yggdrasil were:

- The Well of Mimir – The head of the god of knowledge rested next to a well that was imbued with his powers and could provide information to anyone who drank from it. It was said to be near the land of the frost giants or close to Asgard where Odin could control it.

- Hvergelmir – Described as a bubbling spring rather than a well, Hvergelmir was nonetheless named as one of the water sources for Yggdrasil. It was in Niflheim, the land of ice.

- The Well of Urd – The Well of Fate and the meeting place of the Norns, the location of this well varied in almost every retelling. Some claimed that it was a lake below the tree, some placed it near Asgard or Midgard, and others said that it was above the tree itself and a root bent toward the sky to reach it.

Because it had only three sources of water, Yggdrasil was said to have just three enormous roots. Each went to one of the wells and arched above and between the worlds to reach the water.

These wells also served other purposes.

Hvergelmir is mentioned in the creation myth as of of the sources of all life.

The cold temperatures around it caused the well’s water to freeze, forming Niflheim before the other worlds were created. The heat of Muspeheim caused small amounts of the ice to melt and drip down toward the realm of fire.

Most of this water evaporated before it reached Muspelheim, however. The mists that eventually filled Ginnungagap coalesced into Ymir and Audumbla, the giant and cow who were the first living things.

The Well of Mimir was a constant source of knowledge. Odin consulted Mimir, the disembodied god who guarded the well, but was eventually allowed to sacrifice his eye to the water to take a drink of it himself.

This water gave Odin knowledge, likely of a magical nature. When he hanged himself, as well, knowledge was revealed to him in the water.

The well Odin looked down into is never named, but it may have been the Well of Mimir revealing further knowledge. It could also have been the Well of Fate, although Odin’s new wisdom did not give him the foresight that that well provided.

The Well of Urd

Beneath the World Tree was the third well in Norse cosmology, the Well of Urd, or Fate.

Urd could refer to fate as a concept or one of the three goddesses that were said to control it.

The Norns were the goddesses who gathered around the Well of Urd beneath Yggdrasil. Usually named as Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld, they represented the future, present, and past.

The Norns were goddesses who had a unique ability to manipulate fate. Usually pictured as strands of thread, they measured out the length of a person’s life and wove the complex tapestry that would determine the course of a life.

In other accounts, however, fate was engraved on Yggdrasil itself. The Norns used magical runes to carve what they foretold on the tree’s roots, making fate a permanent part of the World Tree.

The Poetic Edda claims that the Well of Urd is actually a large lake that lies beneath Yggdrasil. It is muddy and covered in a dense loam that makes it impossible for anyone but the Norns to gaze into it.

Shamanistic magic often included looking into a reflective surface, such as a lake or well, to see hidden truths or secret knowledge. The muddy water of the Well of Urd ensured that no one except the Norns could learn anything by looking into it

The Prose Edda, however, says that the Well of Urd is closer to Asgard, the home world of the Aesir bridge.

Snorri Sturluson, the writer of the Prose Edda, says that the gods cross the rainbow Bifrost bridge not only to reach the land of men, but also to reach the well. Each day they gather around it to hold court and discuss their affairs.

The Aesir consulted the Norns at these meetings. Although details were rarely given, the Norns were more free with their information about fate than they were in other sources.

Like Yggdrasil, there seems to have been no consensus regarding the location of the Well of Urd. As part of Norse cosmology, it was broadly understood but the details seem to have often been left to the imagination.

Also left open for interpretation is the full extent of the well’s powers. While it is best known as a site of prophecy, the Well of Fate may have also had healing properties.

Decay and Restoration

Yggdrasil was strong and seemingly timeless. Through the ages, however, it showed signs of being under constant attack.

Many of the creatures who lived in Yggdrasil caused damage to it in some way.

Nidhogg constantly chewed on the root that imprisoned him. This not only caused physical damage but also allowed the wyrm’s potent venom to slowly and steadily seep into the World Tree.

The four stags ate away at the upper branches. Thought to represent natural forces or the passage of time, they slowly eroded at the health of the World Tree.

Even Ratatosk, who is often thought to have been a harmless embellishment, may have damaged Yggdrasil. Some historians believe that the squirrel’s rodent teeth were another force that weakened the World Tree.

In addition to these creatures, the tree was slowly dying of other causes. Many sources describe rot and decay as part of the World Tree.

Some said that the tree appeared intact but that rot was slowly growing within it. Others described it as visibly rotting, seeming fine from one side but completely dead on the other.

To combat this steady decay, some writers claimed that the Norms used the Well of Urd to care for Yggdrasil and keep it alive as long as possible.

Each day the three Norns would solemnly fill jars of water from the Well of Fate and take them to the root that lay above it. They would slowly pour this water over the wood and it would nourish the tree and combat its slow death.

Eventually, however, the legends imply that the Norn’s efforts to keep Yggdrasil healthy would fail. Against the combined forces that attacked it, the three goddesses could not maintain the tree forever.

The tree itself would eventually succumb to fate.

Some scholarly believe that a weakening of the sacred tree would eventually lead to many of the events of Ragnarok.

While the World Tree provided a conduit between worlds it also blocked some off. Some sources say that the root that confined Nidhogg shut off the gates of Niflheim while another part of the tree did the same to Muspelheim.

When these roots were weak enough, the inhabitants of these two realms would be able to break free and begin their assault against Midgard.

Niflheim is often interpreted as being the location of Hel’s realm of death, so in addition to Nidhogg and frost giants, the dead would be free to leave the frozen world. From Muspelheim fire giants would venture forth to burn the world.

Although Ragnarok may be caused, at least in part, by the weakening of the World Tree, Yggdrasil would not die entirely. When the rest of the world was remade after the battle, it was implied that new life would flourish within Yggdrasil and the tree would return to health.

The Well and the World Tree

In Norse cosmology, the Nine Worlds existed in or around Yggdrasil, the World Tree.

The exact layout of the cosmology was never made clear in written sources. Even the names of some of the Nine Worlds it supported were uncertain.

Yggdrasil’s true importance was not in its physical layout but in its symbolic meaning.

Yggdrasil was a massive version of the sacred tree, a central aspect of religious life in Germanic cultures. These trees allowed for communication between worlds and were the places where the people of Europe gave sacrifices to their gods.

A myth of Yggdrasil shows how these sacrifices may have been carried out. Odin hanged himself as a sacrifice to himself in the same way his human worshippers would have offered human and animal sacrifces.

Yggdrasil was supported by three wells that each fed a giant root of the World Tree.

One of these was the Well of Urd, or Fate. It was the place where the Norns, a trio of goddesses, foretold and interpreted the events of all lives and worlds, including the fate of Yggdrasil itself.

While the Norns attempted to keep the tree healthy, they knew better than anyone that fate could not be avoided. Internal decay and the effects of the animals that lived in the tree’s branches would slowly weaken the great World Tree.

This decay may have been one of the predicted causes of Ragnarok. The weakened roots may have allowed the monsters on Niflheim and Muspelheim, the primordial worlds to escape and attack Midgard.

Yggdrasil would survive, however, and presumably recover. After Ragnarok, it would provide shelter to the last living man and woman who would leave the refuge of the sacred tree when the world was safe to repopulation.