Norse

Odin: The Wise King of the Norse Gods

Odin: The Wise King of the Norse Gods

Odin was the ruler of the Norse gods, but if you think that means he was only a king you would be mistaken. Keep reading to learn about Odin’s mastery of knowledge, magic, and more!

Óðinn, usually Anglicized as Odin, was the chief of the Aesir gods in Norse mythology. When they joined in a truce with the Vanir, Odin became the de facto leader of both groups of deities.

The most popular image of Odin is as the lord of Valhalla, his great hall in Asgard. There, the god of war gathered the most courageous and fearsome fighters to join him on the field of battle at Ragnarök.

War and kingship were not Odin’s only domains, however. In his legends, he was far more concerned with accumulating magic and knowledge than he was with ruling over the gods.

Odin was a master magician who went to incredible lengths to gain access to new sources of knowledge. From physical sacrifices to subverting his people’s gender roles, the king of the Norse gods would do anything to gain more knowledge.

The Birth of Odin and the Aesir Gods

In the Norse story of creation, Búri was the first god to emerge from ice. From his own body, Búri created more gods including Borr and Bestla.

Borr and Bestla had three sons, Odin, Vili, and Vé.

When the three brothers were born, the Nine Worlds did not yet exist. The empty space of Ginnungagap was the home of a great giant named Ymir instead.

Odin and his brothers trapped Ymir and killed him. They used his body to create land, his blood to make the sea, and his skull to form the dome of the sky.

Ymir’s body became Midgard, the world of men. Odin, Vili, and Vé then used the wood of two trees to create the first people to inhabit this world, Ask and Embla.

The gods made Asgard their home and while Vili and Vé, along with their parents, soon faded out of recorded legend Odin became the ruler of the Aesir gods who lived there. He married Frigg, the goddess of marriage and family.

Together they had three children, Baldr, Höðr, and Hermóð. He also had many children outside of their marriage, most notably the thunder god Thor.

Odin was the ruler of the Aesir, but they were not the only gods in the pantheon. In their early history they fought another group, the Vanir, for control.

The God of War

The Vanir gods inhabited their own world, Vanaheim, and for many years the two families of deities could not agree on who should rule over Midgard.

The Aesir and Vanir fought a war for supremacy. It was here that Odin’s prowess in battle was first felt.

Odin’s name comes from the Norse word óðr, which can mean both “fury” and “ecstasy.” True to his name, Odin was a warrior who loved to fight.

Unlike the other Norse warrior gods, particularly Tyr, Odin was not particularly associated with noble causes or a fight for justice. Instead, he was a fighter who loved the chaos and bloodshed of a battle regardless of its cause.

During his war with the Aesir, Odin established a tradition that would become a hallmark of Viking Age culture. As the two groups of gods prepared for battle, he blindly threw his spear into the Vanir ranks to begin the fight.

The fighters of the Viking Age often emulated this act. Throwing the spear into the opposing force’s ranks signified that all their deaths would be sacrifices to the furious warrior god.

Odin watched battles carefully. While he was not generally concerned with noble causes, he did look for those who fought with particular valor, strength, and courage.

When these men died they would be taken by Odin’s servants, the Valkyries, to his hall. At Valhalla, these honored warriors would feast and fight every night and be revived in the morning.

While the war against the Vanir ended with a peaceful truce, the fights at Valhalla allowed Odin’s favored warriors to enjoy the bloodlust of battle every night. They would continue their endless feasts until they fought for the gods at the end of the world.

Odin’s Quest for Knowledge

Odin loved fights and feasts, but what he craved above all else was knowledge. His search for hidden wisdom and secret truths was one of his most defining characteristics.

He kept two ravens, Huginn (Thought) and Muninn (Memory). They flew throughout the worlds fathering information and secrets to share with him.

One of his first exploits after the war between the gods was to steal the Mead of Poetry from the giant that held it. He seduced the giant’s daughter and tricked her into giving him three drinks of the magical mead before flying away in the form of an eagle.

Odin carefully guarded the Mead of Poetry, although a small amount had fallen to Midgard to give people a rudimentary knowledge of music and art. Those he favored would be given a greater potion and be inspired to write great poetry in his honor.

Odin also possessed the head of Mímir, the god of knowledge who had been killed during the Aesir-Vanir War. He had reanimated the head so Mímir could share his wisdom.

Eventually, he put Mímir beside a well that was imbued with all his knowledge. When told that he would have to pay a dear price to drink from the well, the god pulled out his own right eye as a sacrifice to knowledge.

In another story, the one-eyed god travelled to the land of the dead, Hel, to consult a wise woman who had died many years earlier. There he learned everything she knew of the world including, most importantly to him, how it would end at Ragnarök.

In one of the most dramatic scenes of Odin’s mythology, he made the ultimate sacrifice in search of knowledge that was unknown by any living gods or men.

I ween that I hung on the windy tree,

Hung there for nine nights full nine;

With the spear I was wounded, and offered I was,

To Othin, myself to myself,

On the tree that none may know

What root beneath it runs.

None made me happy with a loaf or horn,

And there below I looked;

I took up the runes, shrieking I took them,

And forthwith back I fell.

-The Poetic Edda (trans Bellows)

Odin offered himself as a sacrifice in his own name. He hung on the branches of Yggdrasil, the World Tree, for nine days and nights without food or water in the same manner that sacrifices were offered to him by the Norse people.

At the end of the sacrificial period, Odin received the knowledge of the magical runes.

Odin thus became a master of magic with a level of knowledge that far surpassed even the other gods. He was still not entirely content, however, and often wandered the world in search of new sources of information.

The All-Father and Other Names

Like gods of many religions, Odin was known by many names. These various titles and epithets referred to his attributes, actions, and domains.

Norse poetry was particularly fertile ground for the creation of new names. Kenning was a linguistic and poetic tradition in Old Norse in which gods, people, items, and abstract ideas were described in roundabout terms.

Blood, for example, was sometimes called “battle sweat” as a kenning. Fire was poetically named “the bane of wood.”

This not only added a flourish to Norse poetry, but was also an honor to Odin himself. As the keeper of the Mead of Poetry, inventive kennings were thought to please Odin and show his favor.

As the god who found the most joy in kennings, Odin earned many of them. Among his many names were:

- Alföðr (All-Father) – This referred to his place as the ruling figure among the gods and his literal status as a father to many of them.

- Glapsviðr (Swift in Deceit) – A way of calling him cunning.

- Fjölnir – Wise One.

- Gestumblindi (The Blind Guest) – One-eyed Odin often took the form of a blind beggar as he wandered Midgard, testing the hospitality of humans.

- Sanngetall – Finder of Truth.

- Asagrimmr – The Lord of the Aesir.

- Hárbarðr – Grey Beard.

- Uðr – Loved, Beloved.

- Viðrir – Stormer.

- Brúni (Bear) – This was not only a form he sometimes took when walking on Midgard, but also referred to his ferocity in battle.

- Gangari – The Wise One.

- Herteitr – Glad of War.

- Svipall (Changer) – Odin was often a shape-shifter in his myths.

- Hroptr – Sage.

- Farmr galga (Gallows’ Burden) – A term commemorating his sacrificial hanging on the World Tree.

- Kjalarr – Nourisher.

- Galdraföðr – Father of Magical Songs.

- Geirvaldr (Spear Master) – Can also mean Master of Gore.

- Hangi – The Hanged One.

- Herföðr (Father of Hosts) – Both anoher term for All-Father and a reference to the hosts of Valhalla.

- Síðskeggr – Long Beard.

- Jölnir – The God of the Yule.

- Sigtýr (War God) – This name refered to Odin as the God of Victory.

- Þekkr (Known) – This meant someone who is known and welcomed in a house or hall.

- Váfuðr – Wanderer.

While the Norse people had many names for Odin, he was still known by even more elsewhere.

Odin was not just a Scandinavian god. The majority of the Germanic peoples of Roman and early medieval Europe worshiped him, under their own names, as their chief god.

In Germanic languages, he was most often known as Wodan or Wotan. These names, along with Odin, had the general meaning of “war god” or “chief.”

Odin’s German name remains in the English language today. The days of the week come from the Germanic gods, and Wednesday is Woden’s Day.

Odin as a Shaman

Many of the secrets Odin learned in his travels were magical in nature. In addition to the runes, he mastered magical songs and learned the lost shamanic knowledge of the distant past.

Odin was often described in mystical and magical terms. He received visions from distant places, for example, while in a trance-like state that made him appear nearly dead.

Odin’s practice of two distinct types of magic was notable in the Germanic world.

He was often associated with a type of magic that was useful in battle. Brought about through songs, rituals, and probably intoxicating drugs, this type of magic made men especially fearsome in battle.

Battle magic in Germanic thinking was typified by the berserkers. These almost legendary warriors entered a magical state in which they were completely consumed by bloodlust, making them both more ferocious and harder to wound.

The other type of magic, seidr, was less expected for the chief of the gods.

Seidr magic was concerned with the workings of fate. Fate was woven by the three Norns, and practitioners of seidr sought to understand and rework the threads.

This was a more feminine type of magic, as weaving was a task almost exclusively performed by women in Germanic society.

Seidr magic was epitomized by völvas, wise women. They were fortunetellers and healers who often wandered from place to place.

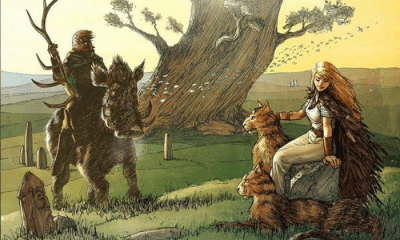

Freya was the goddess of the völva and was said to be the only goddess whose magical abilities came close to matching those of Odin. While Freya could also see the strands of fate however, she was unlike Odin in that she rarely revealed her knowledge of the future to others.

Women who practiced magic were distrusted by most of society, but in the patriarchal culture of the Viking Age those who ventured outside of their gender norms were viewed with even more suspicion and scorn.

Odin was the exception to this. He often practiced forms of magic aligned with seidr but retained his masculinity through his roles as a ruler and warrior.

Odin’s mastery of both masculine and feminine forms of magic set him apart as one with unique knowledge. While ancient writers sometimes alluded to Odin’s loss of masculine honor due to the magic he practiced, his use of masculine battle magic balanced any perceived feminization.

How the God Appeared to Men

In modern media, Odin is most often depicted as the stern and heavily-muscled leader of the Norse gods. He epitomizes masculinity and nobility.

In the Norse world, however, Odin was believed to be a shapeshifter. The image of a powerful lord of the Aesir was one that the people of Scandinavia believed he rarely took, especially when he visited Midgard.

He sometimes took the form of an animal, particularly an eagle, to travel between worlds unnoticed. In his search for knowledge, however, he preferred to walk among humankind to learn their secrets.

Odin generally traveled through the world of men in disguise, both to blend in with humanity and to avoid confrontations with the jötnar. When he interacted with mankind, he rarely appeared to be particularly powerful or strong.

Instead, Odin’s human form was that of an older wanderer.

In this form, he had a long gray beard and often appeared to be weak, although he still retained his divine strength when needed. He walked with a staff that marked him as a practitioner of seidr magic but also gave him an even older and more frail appearance.

In these stories, Odin is most often described as wearing a long cloak and hood. This makes him appear mysterious but would have also been common traveling apparel in Germanic societies.

One of the only ways a person could identify Odin was by his missing eye. He was also often visited by his ravens and wolves as he travelled.

The image of the wandering sage allowed Odin to travel freely throughout Midgard without being noticed by humans or the jötnar. Even the other gods were sometimes thrown off by his human disguise.

Hospitality was an important virtue in Scandinavia since a lack of food or shelter could quickly turn deadly in the harsh climate of the North. The belief that any traveller could be Odin in disguise helped to enforce the laws of hospitality.

Odin did not strictly enforce these laws, however. He was happy to favor those who broke those laws, even thieves if they did so with cunning and the joy of óðr.

Odin as the God of Ecstasy

Odin’s name was related to the Norse word óðr, which could mean both “ecstasy” and “fury.” In all his roles, he epitomized all meanings of the world.

As the chief of the Aesir gods he was a great warrior. Rather than concerning himself with law or nobility he fought with pure óðr, taking joy in the bloodlust and madness of battle.

He was also a god of magic, the óðr of finding hidden knowledge and influencing the affairs of the world and fate.

The magic and fury combined in the berserkers, men who used magical means to enter a frenzy in battle. But Odin was also a master of the more feminine form of magic, seidr, that worked with the threads of fate as they were woven by the Norns.

Odin would do anything to add to this knowledge. He famously travelled to Hel to learn about Ragnarök, pulled out his own eye to drink from Mímir’s Well, and hanged himself as a ritual sacrifice on Yggdrasil to learn the secrets of the runes.

Odin was more often seen as a wandering sage or even a beggar than a powerful king. Among his many forms and names, he used the image of a gray-bearded traveller to learn the secrets and news of the human race.