Norse

Frigg: The Queen of the Norse Goddesses

Frigg: The Queen of the Norse Goddesses

Frigg was the queen of the Norse gods, but how much do you really know about Odin’s wife? From her role as a mother to her greatest sorrows, keep reading to learn all about Frigg!

In some pantheons, the gods and goddesses are on nearly equal footing. The Greeks, for example, often had their deities in gendered pairs.

The Norse pantheon, however, was not as evenly divided as some. While many gods have numerous myths and extreme powers, not much is known about most of their goddesses.

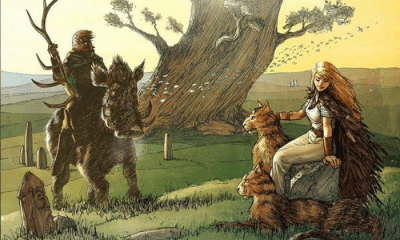

Frigg is one of the few Norse goddesses to play a major role in several myths. As Odin’s wife, she was the most powerful goddess of the Aesir.

Her role, however, went beyond just that of a wife.

Frigg was a powerful deity in her own right. Her stories show that her maternal protectiveness made her a formidable match even for her husband.

The Origins of Frigg

Like most of the Norse gods, Frigg does not have an origin story in her mythology. Historians, however, can see an origin story for her character in history.

The Aesir gods were Germanic. They were brought with the ancestors of the Viking Age people when they moved into Denmark and Scandinavia from Central Europe.

Frig is attested in nearly all the Germanic languages we have records from. In Old German she was Frija, the Saxons called her Fri, and her Old English name was Frig.

All of these names came from the same linguistic root. The proto-Germanic *Frijjo was a feminine word meaning “beloved,” which also gives the root of the word “free.”

Because few written records survive from most of these cultures, it is impossible to say how similar the individual stories of these goddesses were. The fact that hers is one of many names that remains similar, however, implies that there were similarities in how the goddesses were seen across Europe.

For example, nearly every tradition seems to say that the goddess is the wife of the local version of Odin.

In a German poem from the 10th century, for example, Woden and Frija are linked in healing the horse of Balder, their son.

The founding story of the Langobards, a Germanic tribe in northern Italy, even more clearly shows the relationship.

According to their legend, a small tribe ruled by a woman named Gambara was threatened by the Vandals. The Vandals prayed to “Godan” for success, but he replied that he would favor whoever he saw first in the morning.

Gambara’s sons, meanwhile prayed to Godan’s wife, Frea. She told them to have the women of the tribe tie their hair around their faces and stand with the men when the sun rose.

As Godan slept, Frea turned his bed to face toward Gambara’s tribe. Believing that the small tribe was much larger because the women looked like bearded men, he granted them victory and the name Langobards, or “Long-Beards.”

The story shows that a similar goddess was the wife of Odin, or Godan, as far away as Italy. Not only was the relationship maintained, but her characterization as a caring goddess was as well.

The Mother Goddess

Frigg is often interpreted as a mother goddess, both because of her position and the ways she was described.

The wife of the chief god s a maternal figure in many Indo-European traditions. Hera, for example, was the Greek goddess of marriage and the family largely because of her relationship to Zeus.

Frigg is usually seen in the same way. Even if few gods are specifically named as her children in most myths, as the wife of the All-Father she served as a symbolic mother figure.

In the Prose Edda, this symbolic relationship is taken more literally.

Snorri Sturluson, writing in the Christian era, often elaborated on existing myths to make them into more cohesive and tidy narratives. To do this, he often took ideas that were tenuous or only implied in the past and wrote them more fully into his stories.

In one section of the Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson named Frigg as Odin’s wife and claimed that all the Aesir were descended from them.

He furthered this claim by giving Frigg the alternate name Jordin, or “Earth.” He positioned Frigg not only as a maternal figure, but as the Mother Earth archetype from which all life descends.

He somewhat contradicts this, however, by giving Frigg a previously unnamed father. Fjorgynn is attested nowhere else but the feminine form of the name, Fjorgyn, is named elsewhere as the mother of Thor.

Outside of Snorri Sturluson’s additions to the stories, however, Frigg is most often interpreted as a goddess of marriage and motherhood because of the myths that involve her. Her myths generally show her not only as Odin’s wife, but also as a protective mother figure.

The Sorrow of Frigg

The most well-known stories of Frigg’s maternal actions involves the two gods named specifically as her sons, Baldur and Hodr.

The beginning of this tale is, that Balder dreamed dreams great and dangerous to his life. When he told these dreams to the asas they took counsel together, and it was decided that they should seek peace for Balder against all kinds of harm. So Frigg exacted an oath from fire, water, iron and all kinds of metal, stones, earth, trees, sicknesses, beasts and birds and creeping things, that they should not hurt Balder.

-Snorri Sturluson, Prose Edda, Gylfaginning (trans. Anderson)

Frigg secured protection for her son, so Baldur was almost entirely immune to damage. The other gods made a game of this, throwing various objects at him to watch them swerve in midair to avoid hitting his body.

When Loki saw this game, he was curious about how Baldur could be so well protected. He disguised himself as an old woman and easily got the answer from Frigg.

He also learned that only one item in the Nine Worlds had been ignored when she extracted her promises. The mistletoe that grew near Valhalla had not promised Baldur protection, but she thought little of such an insignificant plant.

Loki saw an opportunity and crafted an arrow from that same mistletoe. To avoid suspicion, he offered it to Hodr.

Baldur was a glorious and well-loved god, but Hodr was less fortunate. He had been born blind and was always excluded from many events of Asgard, including the current game.

Loki offered Hodr the arrow so he could participate. He even helped the blind god to aim it since Hodr could not see his target.

The arrow struck true and killed Baldur instantly. Loki slipped away before the blame could be placed on him.

The gods were heartbroken at the death of their most well-loved comrade. Frigg, in particular, was consumed by grief.

Crying, she asked if any of the gods would travel to Hel. She hoped they could convince the goddess who guarded the dead to release Baldur from her realm.

Hermod, who some sources describe as Frigg’s third son, took up the quest. He borrowed Sleipnir and made the arduous journey to the grim world of death.

Hel agreed to release Baldur on one condition: Every living thing in the Nine Worlds had to cry to prove that he was as well-loved and sorely-missed as the Aesir claimed.

The gods traveled through all the worlds to ask every living creature to mourn Baldur’s death. Even rocks and mountains shed tears when they learned that Frigg’s son could be lost forever.

In Jotenheim, however, one giantess refused to weep. Thokk, who was likely Loki in disguise, expressed no sadness so Hel would not let Baldur go.

Later myths show Frigg still mourning the loss of her beloved son.

When Loki interrupted a feast, for example, Frigg commented that if she had a son like Baldur in the room the trickster would be killed in an instant. The gods would eventually ensure that Loki paid dearly for Baldur’s death by binding him.

The death of Baldur was called Frigg’s first sorrow. The second would be the inevitable death of Odin at Ragnarok.

The Attendant Goddesses

Frigg’s husband and sons were not her only companions, however.

While the gods in Norse mythology were divided clearly between the Aesir and Vanir in most cases, the goddesses were a more varied group. They were said to include not only those born into those orders, but jotnar and elves as well.

Frigg was considered to be the foremost of all the goddesses. The only one who came close to matching her in authority and power was Freya.

Often, Frigg is shown as the leading figure among the asynjur, or goddesses. Like a medieval queen surrounded by the ladies of her court, she was the foremost woman of her people.

Frigg was more closely associated with some goddesses than others, however. These included:

- Fulla: Frigg’s handmaid is often shown near her. She carries Frigg’s belongings and serves as a confidante.

- Lofn: The Prose Edda claims that the gentle goddess was given the job of arranging marriages between men and women by Frigg.

- Gna: Frigg’s messenger goddess has a flying horse so she can travel between the worlds to do her mistress’s bidding.

- Hlin: A more militant goddess, Hlin was tasked with protecting all those that Frigg deemed worthy of such attention.

Although Frigg was often shown at Odin’s side, she was important enough to have her own home in addition to his. She lived in Fensalir, a beautiful region of wetlands and marshes.

With her attendant goddesses around her, Fensalir was likely a very feminine place.

Fulla, in particular, was almost inseparable from Frigg. She, too, seems to come from an older Germanic tradition since similarly-named goddesses, such as Volla, are often in the same position.

Fulla’s primary task was to carry a box made of ash wood that belonged to Frigg. Although its contents were unknown, it was given a place of importance.

Fulla was so closely-linked to Frigg that they were even recognized together in Baldur’s death.

When Hermod returned from Hel he brought gifts from Baldur’s wife, Nanna, who had died of grief during his funeral service. In addition to fine linen for her mother-in-law, Nanna sent a ring for Fulla.

Although Frigg’s attendants were less visible and lauded goddesses, they were recognized in their own right. Figures like Fulla served not only as companions and assistants to the queen of the gods, but also as extensions of her own power in influence.

Frigg’s Foster Son

Another well-known myth about Frigg shows that her maternal focus was not only directed at her own son.

In one legend, two young princes were swept out to sea while they were fishing near their home. They washed ashore near the home of an elderly peasant couple who took them in.

The old man fostered the younger boy, Geirroth, while his wife cared for the older brother, Agnar. After a year, the man told the boys that it was time for them to go back to their father’s lands and gave them a boat for the return journey.

Before they set off, however, he pulled Geirroth aside and whispered something to him.

When the boys neared home, Geirroth jumped out of the boat early. He pushed it back out to sea, with his brother still in it, and said that he hoped it went to an evil spirit.

Geirroth returned home to find that his father had died during his time away. As the only known member of his family to survive, he was made king at just nine years old.

Odin and Frigg watched both boys grow. They, of course, had been the old couple who had fostered them and continued to take an interest in their former wards.

Odin bragged that his foster son was becoming a great king while Agnar, stranded on the shores of a wild land, lived in a cave was a giantess. Frigg countered that Geirroth was inhospitable and so cruel that he would probably torture a guest rather than share his wealth.

Odin proposed a bet to prove that Frigg’s claim was false. He returned to Midgard in disguise as a sorcerer to visit Geirroth’s hall.

Frigg had, in fact, been false in her claim but has spoken out of anger to defend her foster son. Unwilling to lose her bet to Odin, however, she sent Fulla to King Geirroth before he left Asgard.

Fulla told Geirroth that a wizard planned to visit his court to bewitch him and destroy the kingdom.

When Odin arrived, giving the name Grimnir, Geirroth had him seized. He tortured him for eight nights trying to get him to confess to plotting to steal from him.

Grimnir received no kindness as a guest until the ninth night when Geirroth’s son, who had been named after Agnar, offered him a drink of ale to ease his suffering.

While Frigg was not mentioned at the end of the poem, it was clear that she had won the bet. The only kindness Odin received was from Agnar, albeit a different Agnar than Frigg had defended.

The fact that she did so with trickery, however, can be seen as proof of Frigg’s fiercely protective nature. To save her foster son from slander, she would go so far as to have her own husband imprisoned and tortured.

A Single Goddess?

The only goddess who rivaled Frigg in authority and importance was Freya. Some historians believe that there was a good reason the Vanir goddess was so close to the Aesir queen in power.

A theory has emerged among some scholars that Frigg and Freya may have been different aspects of the same goddess.

Traditionally, the Aesir and Vanir gods have been seen as pantheons from two separate cultures. When Germanic people moved into Scandinavia, they both absorbed and displaced the indigenous gods that had belonged to earlier cultures in the region.

One of the pieces of evidence given for this theory is the fact that the Vanir gods do not seem to have linguistic or archetypal counterparts in other Germanic cultures. While Odin, Frigg, Thor, and other Aesir gods are seen in many other cultures, the Vanir appear only in Scandinavia.

Freya, however, may be the exception to that trend.

Frigg and Freya’s names are often thought to come from different root words, but they are very similar. Particularly in other Germanic cultures, it is easy to see how Fri or Frijja could be related to both Frigg and Freya.

The two also had similarities in their functions.

While the domains of Norse gods were never as clearly stated as those of some other cultures, both Frigg and Freya seem to have been associated with marriage, femininity, and childbearing.

There were more subtle similarities in their stories, as well.

Both goddesses were described as being at least as knowledgeable about fate and what was in store for the future as Odin in various sources. Different texts say that both Frigg and Freya had foresight but never revealed what they knew to others.

Some poems even suggest that Freya was Odin’s spouse instead of Frigg. This seems to be most true in later sources or when he is particularly linked to magic or warfare, both Freya’s domains as well.

Some historians see enough commonalities to believe that Frigg shares a source with Freya. There are many ways this could have come about, however.

Some suggest that the pre-Norse people of Scandinavia adopted Freya from an early Germanic source. When the Norse arrived hundreds of years later, she had already been firmly established as a Vanir goddess.

Others believe that Frigg and Freya began as the same being. Over time, her role became so complex that two separate deities were invented to divide the character.

A third theory is that the two were always understood to be closely related. They may have been two aspects of the same divine form, similar to the way in which many Celtic goddesses appeared as triple beings.

Unfortunately, a lack of contemporary sources from Germanic cultures means that we will likely never have definitive evidence for any of these theories. Whether or not Frigg and Freya were derived from the same source is a question we may never know the answer to.

The Power of Frigg

In Norse mythology, Frigg is usually interpreted as a goddess of motherhood, marriage, and family.

This is largely because of her marriage to Odin. As his wife she was the symbolic mother of all the gods and people who called him the All-Father.

Frigg’s maternal role is emphasized in her myths.

When her son Baldur’s death was foretold, Frigg went to great lengths to protect him. When her efforts failed and he was consigned to Hel, her mourning was intense and lasted through later stories.

As a protective mother figure, Frigg would even challenge her own husband. When he claimed his foster son was a better man than hers, Frigg manipulated events and even had Odin tortured to win their wager.

Frigg fits very clearly into a Germanic archetype. Goddesses with similar names, relationships, and roles can be found in records across Europe.

Some historians believe that she may also be related to a uniquely Scandinavian form, as well. While Freya is generally believed to have no Germanic counterparts, there are enough similarities between her and Frigg for some to believe that they may have had a common origin.