Norse

Njord: The Viking God of the Sea

As the god of the sea and wealth, Njord was a major deity for the Viking Age Norse people. In fact, he was a god who uniquely represented the culture of Scandinavia!

Njord was the god of the sea in Norse mythology. He was said to not only control the sea and wind, but also to provide wealth and have a role in the fertility of crops.

This made him an important figure to the seafaring Norse culture.

He was widely regarded as one of their greatest deities. His importance was emphasized by the fact that he and his children were included in both pantheons of Norse belief, the Vanir and Aesir groupings of gods.

As a member of the Vanir, Njord was not only well-suited to Norse culture. He was uniquely Scandinavian with virtually no known influence from outside religious traditions.

Njord was so distinctly Scandivanian that elements of his worship continued long after pagan belief died out in the region. He was recognized for centuries as a source of bounty and reinterpreted as a legendary king of the Danish people.

Njord in the Vanir and Aesir Pantheons

Njörðr, whose name is typically Anglicized as Njord, was the god of the sea in Norse mythology.

Like many sea gods, he was associated with sailing and fishing. He also had control over the wind.

Njord was also a god of wealth and crop fertility. His association with wealth was likely due to the seafaring culture of the Norse people.

Locally, the sea was an important source of resources. Fish was a staple of the Norse diet.

In the Viking Age, seafaring was also a source of material wealth. Viking raiders brought back gold, jewels, silk, and other valuables from across Europe. Even mundane products like lumber and fur were more easily transported by ship than by land in most parts of the North.

After the raiding parties had scouted territories and subdued their people, seafaring also allowed the Norse to expand their wealth in less violent ways. Danish and Norwegian settlers found new farmland in Britain, Iceland, Eastern Europe, and even North America.

Njord was therefore an important god in the daily lives of many Scandinavians. He was so important that he was considered to be a member of both of their pantheons.

Norse mythology claimed that two groups of gods, the Vanir and the Aesir, had once vied for power. After a long war, they had settled on a truce and exchanged high-ranking hostages to ensure the peace.

Njord had been a leader, perhaps even the chief, of the Vanir. His father was never named, leading some mythographers to infer that he was among the first of the Vanir gods.

He was sent to Asgard to live among the Aesir along with his son Freyr in exchange for the Aesir god Hoenir.

Odin welcomed Njord and Freyr among the Aesir gods and made them priests of the gods’ sacrificial offerings. Njord was thus a Vanir god in origin but counted among the Aesir.

This may have further highlighted his importance. After the truce, the Vanir retained their home in Vanaheim but became largely subordinate to Odin and the Aesir gods. By becoming an honorary member of the Aesir, Njord retained his position of importance.

The Norse believed that Njord’s importance would not diminish over time, either. He was one of the few gods who was destined to survive Ragnarök and would become king of a new race of deities who would rebuild the world.

Freyr and Freya

Njord did not take his place in Asgard alone.

He was accompanied by his son Freyr, a god of fertility, peace, and prosperity.

Freyr is usually considered to be one of the most beloved Norse gods based on surviving writings and iconography. He was said to bring fair weather, bountiful harvests, and pleasure to those who worshiped him.

One medieval writer called Freyr the “most renowned of the Aesir.”

He is often described as the twin brother of Freyja, who joined her family in Asgard.

Freyja is often described as the Norse goddess of love and beauty, a parallel to other the Roman Venus or Near Eastern Ishtar. While her origins were likely different, she too was seen as a deity of femininity, sexuality, and romantic love.

While Njord was sometimes said to have other children, most of these were not even named in written sources. Freyr and Freya were his most famous and well-loved children.

Although they were sometimes called twins, however, there was some disagreement over their origins.

According to several written records, Freyr was the son of Njord and his sister, who was not named in those records.

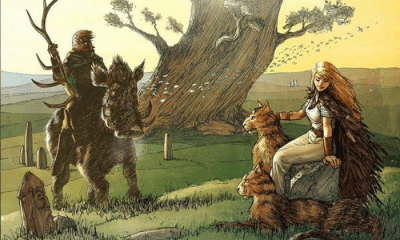

Freyja, however, is often said to have been the daughter of Njord’s famous marriage to the jötun, or giantess, Skaði.

Njord’s Loveless Marriage

The story of Njord’s disastrous marriage began with the trouble caused by the trickster deity Loki.

Loki had traveled to Jötenheim, the world of the giants, and been taken captive by a particularly violent jötun named Thiazi. In exchange for his freedom, he promised to bring the giant the goddess of youth, Iðunn.

When the Aesir learned that Loki had sold one of their own goddesses to a jötun, they threatened to kill him if he could not bring her back. He transformed into a falcon and hurried back to Jötenheim to rescue the goddess from a forced marriage to Thiazi.

Loki gripped Iðunn in his talons and flew back to Asgard. Thiazi, however, turned into a bird as well and followed.

The gods, watching from their walls, saw Thiazi approaching quickly enough to overtake Loki. To save Iðunn they sent up a wall of fire in front of him, killing the jötun instantly.

Loki thought the matter would end there, but Asgard was soon visited by Thiazi’s daughter, Skaði.

She was inconsolable over her father’s death and demanded that the gods repay her for the loss. One of her demands was that she be allowed to marry one of the gods of the Aesir.

Odin agreed, provided that she not be able to make the choice without limits. He decreed that she would have to choose her husband without seeing any part of him but his feet.

Skaði chose the most attractive pair of feet, hoping that they belonged to Baldr. Instead, she chose Njord.

The two were poorly matched. She loved the mountains while he was a god of the sea.

As a compromise, they agreed to spend nine nights at a time in each of their respective halls. They first went to Skaði’s mountain home, Thrymheimr.

After just nine days, Njord was miserable.

“Hateful for me are the mountains,

I was not long there,

only nine nights.

The howling of the wolves

sounded ugly to me

after the song of the swans.

-Snori Sturluson, The Prose Edda (trans. Byock)

Skaði then spent nine days with Njord in his seaside hall Nóatún. She was as unhappy with the cries of the seagulls as her husband had been with the howling of the wolves.

The Prose Edda implies that Njord and Skaði lived separately most of the time. She returned to the mountains and they rarely saw one another after the first eighteen days of their marriage.

Skaði was sometimes named, however, as the mother of at least one of Njord’s children. While the identities of many of his daughters are unknown, Freyr and Freyja lived near their father in Asgard.

The Origins of the Vanir Gods

While Njord has some superficial similarities to sea gods from other pantheons, he appears to be a uniquely Scandinavian character. Few deities from other European religions seem to share his characterization or a linguistic link to his name.

Etymologists have been able to identify only a few gods from nearby cultures that may be linked to Njord. These are:

- Nerthus: The Germanic fertility goddess is linked to Njord primarily through the probable shared root of their names. While some believe that the deity’s gender changed, others believe that Nerthus may be a form of Njord’s unnamed sister, similar to the pairing of Freyr and Freyja.

- Bieka-Galles: The indigenous Saami people of Norway and Sweden worship a god of wind and rain who takes boats and oars as offerings. Folklorists believe that this god was influenced by Njord rather than developing independently, however, because the Saami are not traditionally seafaring people.

- Svafrþorinn: Another Norse deity, he appears in only one surviving line of poetry. Some have interpreted this character as an alternate form of Njord, but etymology makes this unlikely.

These possible parallels to Njord are not only rare, they are highly localized. Only Nerthus, a goddess whose only concrete link is linguistic, existed outside of Scandinavia.

Njord is not the only god of the Norse people to have little connection to other Indo-European traditions. The Vanir gods as a whole seem to be uniquely Norse.

The Aesir gods largely follow established Indo-European archetypes. Thor, for example, is a typical thunder god while Odin has much in common with other king-like deities.

The Vanir as a whole, however, have no such relationship to the other gods of Europe.

The existence of two distinct groups of gods with different cultural backgrounds has led many historians to theorize that the mythological war between the Aesir and the Vanir may have been influenced by a historic clash between two cultures.

They think that the Vanir gods were native to Scandinavia and developed independently of the archetypes of Indo-European religions.

The Aesir, meanwhile, were brought into the region by Germanic peoples from the south.

As in the legend of the gods’ war, neither of the two groups was able to establish full supremacy over the other. Instead they combined their pantheons, trading some of their gods, and created a new mythology in which the two groups coexisted.

Njord and Hadingus

While few outside beliefs seem to have influenced the development of Njord and the Vanir gods, he provided direct inspiration for a later piece of Danish folklore.

The 13th century Danish writer Saxo Grammaticus compiled the history of his country in a book entitled Gesta Danorum. A great patriotic work, it still serves as a key resource for information on Danish history and its monarchs.

While the Gesta Danorum contains valuable historic information, it also incorporates elements of legend. The earliest kings named in the book are based less on historical fact than they are on folklore.

The earliest kings named in the Gesta Danorum may have been recorded in lists on monarchs, but Saxo Grammaticus quite obviously based their biographies on pre-Christian gods rather than historical figures.

King Hadingus, who was said to have ruled during the Viking Age, is one such ruler. His story is clearly influenced by the mythology of Njord.

After the death of his father, King Gram, Hadingus was fostered in Sweden. Historians believe this detail of the story was influenced by the transference of Njord to the Aesir.

Hadingus married Regnhild, who was allowed to choose her husband from among the men at a feast based on the appearance of his feet alone. Like Njord and Skaði, they were unhappy with each other’s homelands and echoed the same complaints about the noises of the wolves and gulls.

The legendary King Hadingus had many adventures that are not directly influenced by Njord’s mythology and may have, at least in part, been inspired by historical records of wars and travels of an ancient king.

Many of the details of his story, however, reframed the mythology of Njord in a mortal, post-Norse context.

Continued Folk Belief

Belief in Njord continued after the Viking Age in more than just the stories of Danish kings, however.

The Christianization of Scandinavia was a gradual process, complicated by the region’s remoteness and difficult terrain. While Christianity had a presence in Norway and Denmark as early as the 8th century, the countries were not officially considered Christian until the early 12th century.

Even at this time, however, the religion was not as strong or centralized as it was elsewhere in Europe. 13th century inscriptions found in Norway, for example, still use runes to invoke the Valkyries and make no reference to Christian beliefs.

Evidence suggests that folk belief, particularly among rural and isolated communities, in at least some elements of paganism continued long after the countries of Scandinavia were officially Christianized.

In Norway, for example, a tradition of “sea people” continued for several hundred years. Even among Christians, these people were believed to govern over the weather and grant prosperity, leading them to be interpreted as minor versions of Njord.

More tellingly, a Norwegian account from the late 18th or early 19th century showed that some older people still named the Norse gods in their daily life. After a successful night of fishing, one old woman supposedly said “Thanks be to him, to Njor, for this time,” as she brought in a full pot of fish.

The Importance of Njord

As the god of the sea, Njord was an important deity in Norse culture. In addition to controlling the waves and wind, he was believed to be the god of wealth and prosperity.

His children, Freyr and Freyja, were similarly well-loved deities of pleasure and fertility. All three were gods of the Vanir but joined the Aesir as part of the truce between the two groups of gods.

Njord’s promise of luck did not extend to his own marriage, however. When forced to marry a mountain giantess as a result of Loki’s mischief, Njord could not find happiness away from the sea.

Like the other Vanir gods, Njord was a uniquely Scandinavian deity. He had virtually no influence from gods outside of the Norse world, leading some historians to conclude that the Vanir represented native gods of the North who developed independently of Germanic tradition.

In both mythology and history, Njord’s influence extended well beyond the time of the Viking Age.

Folk belief in Njord persisted in some areas long after the Scandinavian kingdoms were officially Christianized. Some of his myths were incorporated into those of legendary Danish kings, rewriting the god’s stories as historical fact.

The Norse people themselves believed that Njord would have a lasting importance in the world. After the destruction of Ragnarök he would lead the survivors in rebuilding a new world.