Aztec

Who Was the Aztec God Quetzalcoatl?

Who Was the Aztec God Quetzalcoatl?

Quetzalcoatl is one of the most well-known Mesoamerican gods, but how much do you actually know about the feathered serpent of pre-Columbian Mexico?

Quetzalcoatl is the most recognizable name among the Aztec gods. This is largely due to the story that the Aztec king welcomed Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, as the reincarnation of the god.

While this legend is disputed, it is clear that Quetzalcoatl was an important deity to the Aztecs and other people of Mexico and Central America.

He was a god of wind, culture, knowledge, and creation. In some stories he created mankind, and in others he worked with his brother to form the earth itself.

Different cultures associated him with priesthood and kingship, further complicating his mythology in later retellings. He was so important that the world’s largest pyramid was just one of many places dedicated to his cult.

Quetzalcoatl was not only one of the most important deities in pre-Columbian Mexico, he was also one of the oldest. From ancient snake gods to Spanish legends, here’s everything you need to know about the most famous god of the Aztecs!

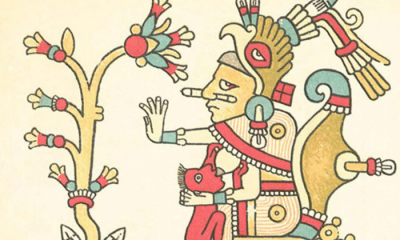

Depictions of Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl is a form of one of Mesoamerica’s most wide-spread images.

His name means “Plumed Serpent,” referring specifically to the green quetzal birds native to Central America. Feathered serpents appear as early as 900 BC in parts of Mexico.

Plumed serpents continued to be depicted in Central American cultures. By the 3rd century AD this was recognizable as a god, who had a pyramid dedicated to his honor in the city of Teotihuacán.

By 1200 AD, Quetzalcoatl’s iconography had become more fixed. Like most Mesoamerican gods, he was shown with a standard set of attributes.

Although early images had shown a serpent, by the classical period of Aztec culture Quetzalcoatl was more often shown with a human body. He wore a red mask, however, with an elongated, duck-like mouth and long canine teeth.

His body is usually black, a color that represents the north in Aztec art. His earrings are made of either jade or spiraling shells.

Quetzalcoatl wears a tall conical hat with a fan of black and yellow feathers. He also has red and green feathers around his head and back.

He sometimes carries flowers or sacrificial tools. Occasionally, he is accompanied by his namesake quetzal bird.

One of his most defining attributes, however, is his breastplate. Known as the Ehecailacozcatl, its swirling design represents the wind.

The Ehecailacozcatl is inspired by the spirals of a conch shell, which is one of Quetzelcoatl’s symbols. Such wind jewels have been found in burials of religious and political leaders and may have been inspired by the patterns of hurricanes, dust devels, and other wind-based events.

Worship and Pyramids

The feathered serpent was a deity who was widely worshiped and persisted for a long period of time. Because of this, the ways in which he was worshipped varied widely.

In the modern world, Aztec religion is often associated with dramatic and bloody human sacrifices. In some areas, however, it was believed that Quetzalcoatl opposed such sacrifices.

In Tenochtitlan, Quezelcoatl’s name was used as a priestly title. Although the city’s main temple was not dedicated to him, the priests of the city took his name and his iconography was prevalent.

The Toltec people, who the Aztecs considered to be their ancestors, used Quetzalcoatl as a title for military and political rulers. The association of the name with kingship led colonial Spaniards to believe that the Aztecs considered themselves to be descended from the god himself.

At Cholula, however, the god’s cult is most evident. The world’s largest pyramid, Tlachihualtepetl, was dedicated to Quetzalcoatl and was built up at the site over a period of a thousand years.

The Nahua civilization, which included the central Mexican Aztecs, almost universally worshipped Quetzalcoatl among their gods. Although little is known about the specific ways in which he was revered, some historians believe that the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms and other intoxicants may have played a large role.

The Power of Quetzalcoatl

As shown by his spiral jewel, Quetzalcoatl was a god of wind. In Aztec culture, this was considered to be one of the most important primal forces.

Quetzalcoatl—he was the wind, the guide and road sweeper of the rain gods, of the masters of the water, of those who brought rain. And when the wind rose, when the dust rumbled, and it crack and there was a great din, became it became dark and the wind blew in many directions, and it thundered; then it was said: “[Quetzalcoatl] is wrathful.”

-Bernadino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain

The god’s powers extended beyond the wind, however.

In some traditions, he was considered to be the creator of mankind. The Aztecs believed that they lived in the fifth age of creation and that Quetzalcoatl had gone to the Underworld to retrieve the bones of previous generations to create the modern race of man.

Quetzalcoatl stole the bones from the Underworld, taking great risks and evading many traps to bring them to the surface. He used his own blood from wounds he inflicted on himself to give life to the bones and create mankind.

Some said that before this he had helped to create the world itself. Along with one of his brothers, he was instructed by his parents to create the world six hundred years after his birth.

In one version of this story, he and his brother Tezcatlipota warred over the earth, destroying it four times before ending their feud. In another, they worked together to tear apart a monster called Tlaltcuhtli and create the land and its features from her body.

Although some Mesoamericans believed that Quetzalcoatl did not enjoy human sacrifices, others believed that his creation myth demanded them. Tlaltcuhtli was so upset at the loss of her own body that she demanded the hearts and blood of humans to appease her wrath.

Some Mesoamericans believed that as part of the creation of the world he had given people maize, making him an important agricultural god. Others said that he had invented the calendar and books.

Quetzalcoatl was also associated with Venus, the Morning Star, and thus the dawn. One legend claimed that the star was Quetzalcoatl’s heart, placed in the sky after he burned himself alive out of shame for neglecting his duties.

Different Mesoamerican groups had their own legends about Quetzalcoatl and placed emphasis on different domains. Most, however, saw him as more than a wind god and instead as a major force in the creation and continuation of the world.

The Feathered Serpents

Because the feathered serpent was such a widespread and long-lasting archetype, he was known by many names throughout Mexico and Central America.

Today he is known best as Quetzalcoatl, the name he was worshipped by in the Aztec culture. The Aztecs, however, were only a small segment of the region’s people.

What is often called the Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states, established in the 14th and 15th centuries. These were part of the Nahua culture, which included both these states and other independent ethnic groups in central Mexico.

The Nahua largely spoke dialects of the same language, Nahuatl, which helped to unify their culture. The name Quetzalcoatl comes from this language and is most widely-used both because it was recorded by Spanish conquerors and because Nahuatl is still spoken by roughly 1.5 million people.

Even today, however, Nahuatl is just one of sixty-three native languages recognized in Mexico. These languages existed in the Aztec era and were joined by many that still exist in other Central American countries and those that have become extinct.

Quetzalcoatl is thus not only an Aztec god. Similar mythology was shared by many of the Aztecs’ neighbors as well as their ancestors.

Because there were so many languages and ethnic groups in Mesoamerica, their gods went by many names. Names for Quetzalcoatl elsewhere included:

- Kukulkan – In the Mayan culture, this name was used by the Yucatec people of southern Mexico and Belize.

- Q’uq’umatz – Also written as Gukumatz, this name belonged to the K’iche’ Maya. The language is spoken today in the highlands of central Guatemala.

- Xolotl – Among the Aztecs, this was Quetzalcoatl’s twin. Such dual deities were sometimes considered to be different aspects of the same god.

- Ehecatl – In some Aztec areas, such as Tenochtitlan, this was another wind god with nearly identical iconography to Quetzalcoatl. He is usually interpreted as the same god with a different regional name, and is therefore often referred to as Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl.

- Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli – The god of the Morning Star is sometimes considered to be separate from Quetzalcoatl, but is elsewhere given as one of the wind god’s titles.

In addition to these, it was likely that the feathered serpent god was known by dozens, possibly hundreds, of different names. Over more than a thousand years, a similar god was worshipped by virtually every one of Mesoamerica’s related cultures.

Quetzalcoatl as a Fertility God

Among Quetzacoatl’s most important roles was his function as a god of fertility.

Mesoamerican deities often functioned in duality. Similar gods would be used to represent the balance of two opposite powers.

Quetzalcoatl’s twin, Xolotl, was a god associated with death. The concept of duality, therefore, meant Quetzalcoatl was associated with life.

This is also evident in the duality of serpent figures throughout Mesopotamian history. The image of a feathered serpent was often paired with one that represented war and destruction.

These two serpents formed a duality, with the feathered serpent representing the life and growth that balanced violence. Quetzalcoatl was the Aztec version of this plumed snake archetype.

As a wind god, he was also responsible for making the rain fall. This made crops grow and brought water for drinking.

Venus, which the god was closely associated with, appeared in the sky at the beginning of the rainy season. This made it an important sign of fertility because it brought with it the rains that renewed the earth.

Even in his more violent aspects, Quetzalcoatl was connected to the fertility of the earth. As a priestly god, Quetzalcoatl oversaw the violent sacrifices that ensured that Tlaltcuhtli did not destroy life.

Looking at the iconography and retold myths of Mesoamerica, some historians have theories that Quetzalcoatl came to be associated with culture and urban civilization. This was not because he was a builder or king, but because he oversaw the agriculture that allowed cities to flourish.

Identification with the Conquistadors

One of the most often-repeated stories involving Quetzalcoatl was one that spread after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico.

Spanish writers of the 16th century claimed that Hernán Cortés was hailed as the reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl when he arrived in Mexico in 1519. Cortés himself claimed in a letter that the gullibility of the Aztec people helped him to conquer them.

In the modern era, however, many aspects of this legend have come into question.

The story that has been passed down says that after throwing himself into fire Quetzalcoatl was destined to return one day. There is no surviving account of this myth in native sources, however.

Instead, these stories were probably the invention of Franciscan monks who followed the initial conquest of Mexico. Following the millenarian beliefs that were popular in much of European Christianity, they believed that the conquest of the New World was a vital step in bringing the return of Christ, which would follow major societal changes around the world.

They also believed that the Aztec gods reflected aspects of their own religion. Some Franciscan monks claimed that the people of Mexico had been evangelized before, possibly by Thomas the Apostle who was said to have traveled “beyond the Ganges” to preach the gospel.

They therefore claimed that Quetzalcoatl was the Aztec name for Thomas the Apostle and that the naive natives believed that he, like Christ, would one day return to finish converting them to Christianity.

This idea of return stemmed from a supposed speech given by Montezuma, the Aztec ruler, to Cortés when the Spanish arrived at Tenochtitlan. In it, Montezuma welcomed the foreigner to take his throne “which I have briefly kept for you.”

If this speech was actually given, it’s likely that ignorance of Aztec customs and Nahuatl speech patterns was to blame for giving the impression that Montezuma was willingly handing over power to a divine being.

Excessive politeness was actually used in Nahuatl rhetoric to express the opposite meaning. Rather than showing subservience to the invading Spaniards, Montezuma’s claim that Cortés was a gracious ruler was a way of asserting dominance and showing disdain for the Spanish commander.

The connection between Quetzalcoatl and the fall of the Aztec Empire may also have its roots in political events that predated the arrival of Cortés and his army.

The Aztec confederacy was opposed by other Nahua groups to the east. One of these groups centered around the city of Cholula, where the great pyramid was dedicated to Quetzalcoatl.

When Cortés arrived, these factions had been in a state of nearly continuous warfare for seventy-five years. Cholula had been captured by pro-Aztec forces.

Several of the peoples of Eastern Mexico united with Cortés in the belief that he would help them overthrow the Aztecs. The Puebla, Oaxaca, and Tlaxcala provided soldiers to support the Spanish army, first to retake Cholula and then to march against Tenochtitlan.

To these people, who continued to work with the Spanish to expand their territory, the arrival of Cortés did lead to the return of Quetzalcoatl. Rather than the conquistador himself being the wind god, however, it was that his army allowed the Puebla and their allies to reclaim the pyramid of Tlachihualtepetl, the center of Quezalcoatl’s cult.

The Truth About Quetzalcoatl

While Quetzacoatl is one of the most well-known gods of ancient Mexico, he is often misunderstood.

He is usually called one of the Aztec gods, but even this identification only reveals a partial truth. Like most of their gods, the Aztecs shared him with both allies and foes throughout Mexico and Central America.

Among these Mesoamerican gods, Quetzalcoatl was also one of the oldest. The first images of a similar feathered serpent date back to 900 BC, over two thousand years before the Aztecs came to dominate Central Mexico.

As a god of wind, Quetzalcoatl was also an important fertility deity. He drove the winds that brought rain and allowed plants to grow.

Quetzalcoatl was so closely linked to fertility and creation that many groups held him to be the creator of mankind. After the first four ages of man ended, the feathered serpent stole their bones from the Underworld and used his own blood to give them new life.

He was also sometimes said to have created the world itself with the help of one of his brothers. In one myth tied to this belief, the two killed a great monster and used its body to craft the world.

The widespread worship of Quetzalcoatl may have even played a factor in the belief that the natives of Mexico identified him with the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. The Spanish helped non-Aztec groups reclaim territory that included a massive pyramid dedicated to Quetzalcoatl.

While this link between Hernán Cortés and Quetzalcoatl remains popular, it is likely based more in Spanish beliefs and misunderstanding than the religion of the Aztecs.

Although Montezuma did not likely believe Cortés to be the reincarnation of the wind god, the popular legend has made Quetzalcoatl the most well-known god of Mesoamerica.