Aztec

Xochiquetzal: An Aztec Goddess of Beauty

Xochiquetzal: An Aztec Goddess of Beauty

Xochiquetzal was renowned as the most beautiful of all the Aztec Gods. Keep reading to learn about the Aztec goddess of love and the surprising way she has survived in the modern era!

The Aztec pantheon had many goddesses who were associated with fertility. They made crops grow and brought life to both people and the earth.

Perhaps the most popular of these goddesses, however, was Xochiquetzal. She represented beauty, pleasure, and desire in addition to childbirth and marriage.

Unfortunately, gaps in the historical record mean that few details survive about Xochiquetzals’s cult. We cannot be sure, for example, who her family was or what her role was in many myths.

What does survive, however, shows us that Xochiquetzal was a goddess who was revered by many people and loved by many gods. While many of her myths have been lost, enough remains to show that Xochiquetzal was a powerful and complex goddess.

How Xochiquetzal Was Portrayed

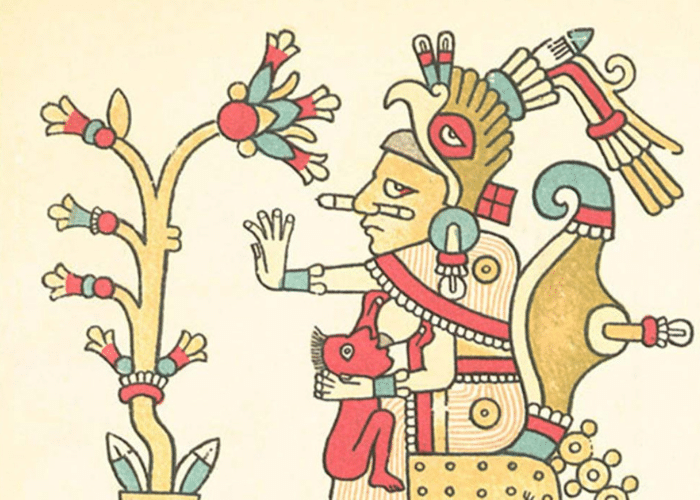

Xochiquetzal’s name incorporates the word xochitl, or “flower.” Flowers were, in fact, central to her imagery. She is usually shown adorned or surrounded by flowers, a symbol of feminine fertility in Mesoamerican cultures.

She was also shown with other hallmarks of female beauty.

Xochiquetzal was depicted in rich garments and luxurious jewelry. She wore a colorful, detailed gown, a mantle of precious quetzal feathers, and the sandals that were indicative of the upper classes.

She also wore a large number of bracelets and necklaces. She usually had large earrings, another symbol of status in Mesoamerican cultures.

One of Xochiquetzal’s most defining attributes was a large, often exaggerated, nose piercing. Like many aspects of her iconography, this also emphasized her high status.

The clothing and jewelry she was shown with were so luxurious that Xochiquetzal became the patroness of such items. Among her worshippers were the craftsmen who made luxury items for the Aztec elite.

Her association with markers of status was not the only thing that set Xochiquetzal apart, however.

The Aztec pantheon included many goddesses who were connected to fertility and beauty. Among all of these, Xochiquetzal was the only one to be shown as a young woman.

Most fertility goddesses in Mesoamerican cultures were shown as matrons. They had the features of older, married women.

Xochiquetzal, however, was shown as young.

Xochiquetzal was not only a goddess of fertility and procreation, but also of desire and beauty. She was associated with pleasure and attraction in addition to, or perhaps more than, motherhood and the creation of a family.

Fertility and Weaving

Xochiquetzal was also the patroness of weaving.

Weaving was a traditionally feminine pursuit in most ancient cultures, so it was not uncommon for a goddess of fertility and family to be associated with that artform. In Aztec culture, however, there was a specific symbolism behind Xochiquetzal’s patronage of weaving.

As a weaver worked, her spindle gradually became more round and full as more thread was added to it. In the symbolism of the Aztec world this was likened to the way in which a woman’s body gradually became more full over the course of a pregnancy.

Some historians also claim that there was a cultural connection between weaving and the goddess of desire.

It has been suggested that weavers had a reputation in Aztec culture for promiscuity. Whether this reputation led to their association with Xochiquetzal or grew out of her existing connection to weaving is unknown.

Weaving also played a role in the sacrifices made in Xochiquetzal’s honor.

Her sacrifices were made during the festival of Hueypachtli, which was held in honor of the god Tlaloc. Offerings of flowers and libations were given to Xochiquetzal.

As was common in Mesoamerican rituals, a human sacrifice was also given. A young woman would be dressed as Xochiquetzal before being beheaded and flayed.

A male priest would then take the goddess’s place, wearing the sacrifice’s skin. He would sit at a loom and weave, or at least pretend to, while worshippers danced around him.

Xochiquetzal and the Moon

As a fertility goddess, Xochiquetzal was also connected to the moon.

Many anthropologists believe that Xochiquetzal evolved from a Mayan deity known only as Goddess I. Like Xochiquetzal, she was a young fertility goddess associated with weaving and childbirth.

Xochiquetzal is less directly connected to the moon in surviving myths and images, but some remnants of the belief can still be seen in surviving legends.

For example, she is closely linked to Tezcatlipoca, the god of the night sky. Tlaloc, whose festival included her rites, was the god of water.

Water and the moon were closely linked in ancient Mesoamerican religions because the moon influenced the tides. It also influenced women’s menstrual cycles and fertilized the land, giving it important connections to goddesses of fertility and motherhood.

The connection between the moon and a fertility goddess is common across many ancient cultures. Most religions thought of the moon as feminine and connected to intimacy at night.

The cycle of the moon also shared the symbolic growing roundness that made spindles a symbol of Xochiquetzal. This further connected it to the idea of pregnancy and, thus, childbirth and femininity.

According to some historians, the moon’s movement across the sky provides another link to the mythology of Xochiquetzal. The goddess’s many supposed husbands link her to the moon and other heavenly bodies.

The goddess of the moon moves swiftly across the sky…seemingly visiting different planetary lovers along the way, before returning to stay with her solar husband for several days each month.

-Susan Milbrath, In Chalchihuitl in Quetzalli: Mesoamerican studies in honor of Doris Heyden, ed. Eloise Quiñones Keber (2000)

The Goddess’s Marriages

Unlike most other Aztec gods, there is no surviving account of Xochiquetzal’s origins. Her parents and extended family are unknown.

All that is known of her family is that she was the twin sister of Xochipilli. The two are often shown together in art and share many attributes.

Xochipilli was the god of art, music, and dance. He was also a god of love, although he was specifically associated with homosexuality and prostitution rather than fertility.

Xochiquetzal’s brother was also said to be her first lover. According to some legends, Xochipilli was punished for this by being turned into a scorpion.

Her twin was not the only god Xochiquetzal was romantically connected to, however. The gods described as her husband in various myths included:

- Centeotl – The god of maize, he was likely connected to her because of their shared domain over fertility.

- Piltzintecuhtli – He was the god of the sunrise, healing, and hallucinogenic drugs.

- Xiuhtecuhtli – This was the god of heat and fire. He was the patron of emperors and merchants as well as the god of time and the year.

- Tlaloc – The god of rain was one of the most widely venerated among the Aztecs and related cultures.

- Tezcatlipoca – The god of the night sky was also one of the four principle creator gods of Aztec mythology.

While Xochiquetzal was connected to many gods, the legend of her marriage to Tezcatlipoca is the most well-known.

According to most surviving accounts, Xochiquetzal had already been married at least once before she married Tlaloc, the god of water and rain. The two worked together to make the world fertile.

Tezcatlipoca, however, was jealous of Tlaloc’s beautiful wife. He kidnapped Xochiquetzal and forced her to marry him instead.

Tezcatlipoca held Xochiquetzal in his realm and challenged any of the other gods to come retrieve her. Tlaloc took up this challenge and journeyed to Tezcatlipoca’s home to rescue his wife.

Tlaloc was successful and Tezcatlipoca was forced to let Xochiquetzal return to him. As one of the world’s creators, however, he forbade Xochiquetzal from returning to the realm of mankind.

Xochiquetzal was reunited with Tlaloc but could never go to earth. Instead, she was confined to the gods’ land of origin, Tamoanchan, which bloomed with flowers but was otherwise cold and desolate.

Many images show Xochiquetzal holding or nursing a child. While the identity of this baby is unknown, some myths suggest that she may have been regarded, at least in some areas, as the mother of Quetzalcoatl or another sun god.

How Women Were Created by Xochiquetzal

According to Aztec legend, the world was created by four gods. Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, and Huitzilopochtli worked together to create the earth and the first man and woman to live there.

This man and woman had a son named Pilcetecli. Because there were no other humans, however, Pilcetecli had no woman to marry.

Without another woman, the human race would die out, so the gods looked for a way to create a bride for Pilcetecli.

They used Xochiquetzal’s hair to fashion the second woman. Pilcetecli’s marriage to this woman was the first to take place.

Because of this, Xochiquetzal was the ancestress of all people on earth. All women inherited their beauty and desirability from her.

This also made Xochiquetzal the patroness of childbirth. Because part of her had been used to ensure that future generations of human children would be born, she had a vested interest in the process.

She was thought to not only have dominion over the desire and love that created children, but to also watch over pregnant women and protect them in childbirth.

Changes to the Maiden

Many of Xochiquetzal’s attributes and myths were likely taken from the Mayan religion. The use of her hair in creating women, for example, is probably tied to the fact that the Mayan Goddess I’s pictographic representation is a lock of hair.

Most Aztec gods and goddesses had a similar origin. The cultures of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were all closely related and their deities very closely followed archetypes that had existed for hundreds of years.

In the 16th century, however, the people of Mesoamerica were brought into contact with a much different religious tradition.

By the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, most of Europe had been Christianized for a thousand years. As part of the Roman Empire, Spain had been introduced to Christianity early in that religion’s history.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas, one of their missions was to convert the “heathen” natives to their own religion. Although both Spanish armies and missionaries committed atrocities against the native people, they believed that they were saving souls by introducing Christianity.

To promote their own religion, the Spanish missionaries turned to one of the tactics that had been used in the Roman Empire and the early medieval era in their own homeland. They associated local gods and goddesses with figures from the Christian faith.

The Romans had done the same by drawing parallels between their own pantheon and those of the Germanic tribes. Because Christianity was monotheistic, they recast the gods of Ireland, Eastern Europe, and other regions as saints, angels, and demons.

The Spanish drew from this tradition in the New World, finding parallels between Aztec gods and figures from the Christian tradition. However tenuous these links were, they provided a way for missionaries to make their religion feel familiar to the Mexican people.

While Xochiquetzal was a goddess of sexual desire and love, Spanish missionaries were drawn to the way in which she was portrayed. They took their interpretation of the Aztec goddess from one of her alternative names, Ichpochtli, meaning “maiden.”

In Aztec culture, this name had referred only to her age. Xochiquetzal was called “maiden” simply to denote a young woman, in contrast to other goddesses.

To the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, however, “maiden” had implications of chastity and virtue. Thus, they linked a goddess of desire to the Virgin Mary.

Many historians directly link Xochiquetzal to the Virgin of Ocotlán. This apparition of Mary was said to have been seen in 1541.

Legend says that Juan Diego, a Catholic convert who worked at a Franciscan monastery, was fetching water from a spring to take to his family, who had fallen ill during an epidemic. A beautiful woman appeared to him and told him that the water would cure anyone who drank from it, so Juan Diego was able to save his entire village from the illness.

The priests believed his account because he was a faithful altar server in their church. They went to the stream that night and found a fire that burned brightly but did not consume the trees.

Feeling drawn to a particularly fat tree, the friars broke it open. There they found a statue in the likeness of the Virgin Mary.

A wooden statue of the Virgin of Ocotlán remains the focal point of the local church. She was officially canonized by the Pope in 1909 and is now the patron saint of the states of Puebla and Tlaxcala.

Xochiquetzal originated as a Mayan goddess of love and beauty. She continued to evolve, however, into an image of the mother of Christ in the Catholic faith.

The Worship of Xochiquetzal

In Aztec mythology, Xochiquetzal was one of many goddesses of fertility. Unlike most, however, she was shown as young and beautiful and was thus linked to desire and attraction as well as procreation.

She was also shown with rich clothing, jewelry, and other finery. This made her a patroness of craftsmen and artisans who created the expensive items valued by the upper class.

Xochiquetzal was also a patroness of weavers. This was both because of the association with weaving and femininity and the symbolism of the round, growing spindle representing pregnancy.

The roundness also linked her to the moon, along with some details of her myths. While her exact function as a moon goddess is unknown, most historians believe that she played a role in the lunar cycle.

In surviving myths, Xochiquetzal is romantically linked to many gods. In particular, Tlaloc and Texcatlipoca vied over marriage to her.

She was also the ancestress of all women because her hair was used to make a wife for the first man born on earth.

When Spanish missionaries arrived in the New World, they linked the youth and beauty of Xochiquetzal to that of the Virgin Mary. The goddess of desire was likened to the mother of god, a comparison that is still seen in Mexican representations of the Virgin Mary to this day.