Aztec

The Aztec Death God Mictantecuhtli

Mictlantecuhtli was just one of many Aztec gods associated with death and the Underworld, but he was both the first and the most important of these deities.

The religion of the Aztec people can seem to outsiders like one that is obsessed with death. Gods are often shown as skeletal or bloody, the Underworld is featured often in myths, and Spanish conquistadors painted a brutal, and probably exaggerated, picture of human sacrifice on an epic scale.

To the Aztecs, however, symbols of death could also be symbols of life. The two concepts were intertwined in their worldview and neither was possible without the other.

This is the reason that their chief god of the Underworld, Mictlantecuhtli, plays a central role in the story of how mankind was created.

Most souls ended up in Mictlantecuhtli’s realm, making him one of the most important god of the Aztec pantheon. He was so powerful and central to the culture, in fact, that his festival day is still celebrated by people in Mexico and the southern United States.

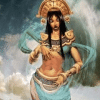

Images of Mictlantecuhtli

Mictlantecuhtli was depicted in Aztec imagery as a 6-foot tall blood-splattered skeleton. While his face was skeletal, large bulging eyes were set into his eye sockets.

His jaw was often opened widely to take in the stars that sank into the Underworld during the day. He often posed with his arms up in a threatening stance.

Like many Mesoamerican deities, Mictlantecuhtli wore an elaborate feathered headdress. This is often abstract in sculpture, but in paintings it can be identified as being decorated with owl feathers and paper banners.

Mictlantecuhtli also wore sandals that indicated his noble position.

In many images, he also wore macabre jewelry. His necklace was a string of human eyeballs and the spools in his ears were made of bone.

These attributes indicated his role as a god of death, but in Aztec iconography they were common for other deities as well. Bones were linked to the cycle of life and death, so they were common in the imagery of fertility and health as well.

The Creation of the Gods

As one of the earliest Aztec gods, Mictlantecuhtli was not born to another set of deities. He was instead created by the four gods who shaped the universe.

Xipe Totec, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Huitzilopochtli were the children of the first two primordial beings, Ometecuhtli and his wife Omecihuatl. When they were six hundred years old, they began to create the world.

The first made the sun, then the first man and woman. Needing to feed the people they had made, they then created maize. Next, they invented the calendar so that the man and woman knew when to plant and harvest the maize.

The four creator gods knew that the man and woman would eventually die, so they soon created Mictlantecuhtli and his wife, Mictecacihuatl. They were installed as the lord and lady of the Underworld and were ready to receive the first souls that died on the newly-populated Earth.

Many deities in Aztec mythology were born or created in similar male and female pairings. While they did not necessarily look alike, Mictecacihuatl was depicted as flayed rather than skeletal, they worked in tandem in a shared role.

For Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl, this role was to rule over the dead.

Mictantecuhtli and the Land of the Dead

Mictlantecuhtli’s name translates simply to “Lord of the Land of the Dead.” Mictlan, the realm of death that he ruled over, was the northernmost and lowest part of the complex Aztec Underworld.

The other regions of the Underworld were reserved for those who died in specific circumstances, such as in battle or by drowning. They would be ruled over by different gods and sometimes be given the chance to resurrect as a different creature.

Mictlan, however, was where most souls ended up. Those who died unremarkable deaths from illness or old age belonged to Mictlantecuhtli.

Unlike some cultures, the Aztecs did not believe that the gods of the dead passed any judgment on them. One’s fate in the afterlife was not based on actions or moral virtue, but only on the manner of death.

Because so many souls ended up in Mictlan, Mictlantecuhtli constantly struggled to maintain order. This often put him in conflict with the gods of creation and fertility because an overabundance of new souls would lead to chaos in his realm.

The Aztecs viewed Mictlantecuhtli as a powerful god, but not an evil one. His purpose was to rule over the Underworld and he had no particular animosity for the living.

The first Europeans to encounter images of the Aztec gods, however, saw the skeletal lord of the dead in a much different light. They described Mictlantecuhtli as:

“The lord of the underworld, Tzitzimitl, the same as Lucifer.”

-Friar Pedro de los Rios, Codex Vaticanus 3738

The Animals of Death

Like many cultures, the Aztecs often associated their gods with specific plants and animals they saw on Earth.

Unsurprisingly, Mictlantecuhtli was paired with several animals who were associated with the night and dark spaces. These included:

- Owls – The nocturnal birds provided the feathers for his headdress. Their wide eyes also mirrored his.

- Bats – Bats emerge only at night. Because of the geology of Mexico and Central America, they often come from cave fissures that give the impression that they’re flying out from the Underworld.

- Spiders – Spiders were associated with death and darkness in many parts of the ancient world whether or not they were venomous.

- Dogs – Around the world, dogs were often said to accompany the souls of the dead on their journey or guard them when they reached the Underworld.

Mictlantecuhtli’s association with dogs was pictured in the calendar of the Aztecs. Each of the twenty gods represented was given a corresponding pictograph for their day in the calendar cycle, and Mictlantecuhtli was the god of Itzcuintli, the dog.

This meant that Mictlantecuhtli was responsible for providing the souls for anyone born on a day of the dog sign and for those born on his separate day of the week, which was the sixth day of a thirteen day week.

Mictantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl

One of the most famous stories involving Mictlantecuhtli illustrated the connection between death and life in Aztec thought.

In the story, Quetzalcoatl journeyed to the Underworld to retrieve the bones of the first people who had died. The human race, descended from just one man and one woman, was dying out quickly and the gods wanted to use their bones to create more people.

Mictlantecuhtli did not want his realm to fill too quickly, so he attempted to trick Quetzalcoatl. He said that the other god could take the bones of the surface if he could travel through Mictlan four times while making a shell sound out like a horn.

Quetzalcoatl believed this would be an easy task, but Mictlantecuhtli gave him a horn that had no holes for him to blow through.

Undeterred, Quetzalcoatl called on worms to come out to bore holes in the shell. He then called on bees to fill the shell. Their buzzing made a constant trumpeting sound inside the shell.

The challenge completed, Mictlantecuhtli had no choice but to give up the bones of the dead. He tried to change his mind, but Quetzalcoatl quickly scooped up the bones and fled toward the surface with them.

This angered Mictlantecuhtli, so he ordered his minions to dig a deep pit along the route the other god would be taking. A quail then startled Quetzalcoatl, causing him to fall into the deep pit.

Quetzalcoatl appeared to be dead, although he was revived. The bones, however, were scattered and broken.

Quetzalcoatl gathered up the pieces and took them to a sacred place of creation to make them living men and women. Because the bones were broken, however, people come in many different sizes.

The Festival of the Dead

Because most souls ended up in the land of Mictlantecuhtli, he was the most important god in the rituals surrounding death.

During the month of Tititl, an impersonator of the god would be sacrificed at one of the great temples. This brutal tradition, however, has been forgotten in favor of the Aztec holiday that celebrated Mictlantecuhtli.

When a person died their remains were cremated and a period of mourning was observed. In Aztec belief, this was only the beginning of the soul’s long journey to Mictlan.

There were nine realms in the land of the dead and a soul would have to travel through all of them, facing many trials and obstacles along the way, to reach Mictlan. This journey would take four years.

Once each year, however, the Aztec people celebrated the festival of Hueymiccaylhuitl, the Great Feast of the Dead. On this day, they believed they could communicate with those souls still making the trip through the Underworld and even help them in their journey.

Hueymiccaylhuitl was a time of celebration in which people believed they were once more in the presence of loved ones they had recently lost. They believed this was a happy time for the dead as well, since Hueymiccaylhuitl was the only time when they could see their living family members.

The Great Feast of the Dead also gave families an opportunity to leave more offerings of food and goods for the dead to carry with them. When souls reached Mictlan they gave these offerings to Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacihuatl, so more and better offerings would appease the chthonic gods and help to ensure the soul’s happiness in Mictlan.

With the arrival of European missionaries the Aztec religion was largely overtaken by Catholocism, but some traditions lived on. Today, the Great Feast of the Dead is celebrated in parts of Mexico and the United States as Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

The modern celebration has incorporated Catholic elements and falls on the Feast of All Souls, but many of the images and traditions hearken back to Aztec tradition. It is a celebration of the dead that combines macabre imagery with the atmosphere of a carnival.

The modern sugar skulls are made in the image of Mictlantecuhtli and many families still gather at gravesites to share a picnic meal on what they believe is the one day of the year that their departed loved ones can join them.

Mictlantecuhtli as the God of Death

Mictlantecuhtli was, together with his wife Mictecacihuatl, the lord of the land of the dead in Aztec mythology.

He was usually shown as a skeletal figure with bulging eyes and jewelry made of human eyes and bones. His headdress was made of owl feathers, one of the many cthonic animals associated with him.

The lord and lady of the Underworld were two of the first beings created by the first four gods.

They ruled over Mictlan, the region of the Underworld where most souls ended up. Mictlantecuhtli’s job was only to maintain order in his realm, not to judge or collect the dead.

Because he wanted to maintain order, Mictlantecuhtli often found himself at odds with the gods who focused on creation. When Quetzalcoatl wanted the bones of the dead to make more people, for example, Mictlantecuhtli used trickery and dangerous traps in an effort to stop him.

The Aztec people believed that the souls of the dead journeyed for four years to reach Mictlan. It was a perilous trip through the realms of the Underworld, but once a year those souls could see and receive help from those who were still living.

This feast day is still part of Mexican culture. Blending with Catholic tradition it is now the Day of the Dead, when the descendants of the Aztecs celebrate the deceased and, some believe, have the chance to spend the day in their company.