Greek

Pegasus: The Winged Horse of Greek Mythology

Pegasus: The Winged Horse of Greek Mythology

You’ve seen Pegasus in stories and art, so now learn the origins of the mythical flying horse.

Virtually everyone is familiar with the image of the winged horse. Pegasus, as this creature was known to the Greeks, has been seen in art and appeared in legends for thousands of years.

Pegasus is so familiar in modern works that it can be easy to forget just how ancient his roots are.

The winged horse appears often in Greek mythology as the companion of great heroes and an assistant to the king of the gods himself. A favorite subject of artists, his image has lived on through the ages as one of grace and beauty.

The origins of Pegasus, however, are much darker than his white coat and angelic wings might suggest.

From his unusually violent birth to his commemoration among the stars, here’s everything you never knew about the famous flying horse Pegasus!

The Birth of Pegasus

The legend of Pegasus began with a rather unlikely source – one of the most hideous monsters in all of Greek mythology.

Medusa was once one of the most beautiful young women in the world, until she was raped by Poseidon in a temple of Athena. As punishment for defiling a sacred space, the virgin goddess transformed the girl into a terrible monster.

With serpents for hair and a face that could turn men to stone, Medusa was one of the most fearsome creatures in the world. She and her sisters, the Gorgons, lived in a cave at the edge of the world.

Finally, the hero Perseus was sent to destroy Medusa. While her monstrous sisters were immortal, Medusa could be killed.

With help from Athena, Perseus beheaded the monster. He crept up on her as she slept, using the shining shield of Athena to look at her reflection instead of her petrifying face.

Perseus fled the cavern, aided by the speed of Hermes’s winged sandals and the invisibility granted by the helmet of Hades, as the other Gorgons awoke.

When Medusa was struck by the hero’s sword, her blood spilled on the floor of the cavern in which she and her sisters had made their lair. From this blood her two children by Poseidon were born.

Her son Chrysaor would not play a major role in later myths. He was the father of the giant Geryon, who was the subject of the tenth of the twelve labors of Heracles, but otherwise his name faded out of legend.

Chrysaor was usually shown as human, at least in shape, and his name implies that he bore a golden sword. His absence from later myths suggests that he was mortal and eventually passed away.

Pegasus, however, had a much different fate than his humanoid brother. The immortal horse that was born of Medusa’s blood would become one of the most famous beasts in mythology.

The Horse of the Waters

As a land animal with wings, Pegasus had an obvious connection to both the earth and the sky. More surprising, however, is his connection to water.

Medusa’s father was Oceanus and her mother, Phorcys, was a primordial sea goddess. Medusa herself may have originated as a representation of the dangers of the sea, specifically hidden rocks that could cause shipwrecks.

Furthermore, Poseidon had fathered the winged horse.

The god of the sea was always linked with horses. Many myths said that he had created the first horse, and he was often accompanied by the half-horse half-fish Hippocampoi.

Poseidon’s son by Demeter, Arion, was another immortal horse. Poseidon had turned himself into a stallion to chase Demeter at Arion’s conception.

Pegasus retained this family connection to water. He was mostly associated with fresh water instead of the sea, specifically the cold freshwater springs that were abundant in the mountains of Greece.

In fact, the name Pegasus was thought to come from the site of his birth near the springs, pegai in Greek, that were the source of Oceanus.

Wherever the horse’s hooves struck the land, a spring was said to form. The waters in these springs were said to have almost miraculous qualities.

In his Description of Greece, the 2nd century writer Pausanias described a bathhouse in the city of Corinth, near the temple of Poseidon. One of the sculptures he wrote about was that of Pegasus, which had a fountain of water flowing through the hooves to the well below, most likely a reference to the creation of springs by Pegasus.

At least two springs in Greece were known as the Hippocrene, or “Horse-Spring”, for their connection to the mythical horse.

The most famous Hippocrene spring was on Mount Helicon. The mountain’s other famous spring, the Aganippe, also contains the word for horse in its name.

These springs were famous for their connection to the Muses. According to legend, the waters of Mount Helicon were endowed with the power to grant inspiration.

The poets of the ancient era frequently mentioned the Hippocrene as the source of their abilities, and Mount Helicon was the centre of devotion to the Muses.

Today, Hippocrene continues to be used as a word for poetic inspiration. From the ancient writings of Hesiod to the more recent works of Longfellow, poets have described themselves drinking of the spring’s waters.

Another spring connected to the winged horse was the Pirene in Corinth. Said to be his favorite watering hole, the horse’s constant visits ensured that it never ran dry.

This spring would feature in the most famous story of Pegasus told in the Greek world.

Pegasus and Bellerophon

The most well known of the myths that feature Pegasus is that of Bellerophon.

The hero had been born in Corinth, but exiled on charges of murder. The king of Tiryns took mercy on him and gave him refuge in his palace, but the handsome young man attracted the attention of the queen during his stay there.

As an honorable man, Bellerophon rejected the queen’s advances. Out of spite, she told her husband that their guest had attempted to assault her.

The king could not offend Zeus by killing a guest under the same roof that had sheltered him. Instead, he sent Bellerophon to his wife’s father, Iobates, with a letter ordering his execution.

Iobates, however, did not read the letter for nine days. Having welcomed Bellerophon into his home all that time, he too would be in violation of Zeus’s sacred laws of hospitality if he attacked his guest.

Iobates came up with a plan, and ordered his now unwelcomed gest to kill the Chimera. The king was certain that this task would result in Bellerophon’s death without directly violating the laws of hospitality.

The Chimera was a fire-breathing beast that had ravaged the countryside of a neighboring state, Lycia. With the body of a goat, the tail of a snake, and the head of a lion, it was a terrifying creature.

On his way to confront the Chimera, and probably meet his doom, Bellerophon happened upon a famous seer, Polyidus. This soothsayer had saved the life of Prince Glaucus of Crete while serving under King Minos.

The man told Bellerophon that in order to win the fight against the Chimera he needed to seek the aid of Athena in taming Pegasus. To do so, he would have to fall asleep in the goddess’s temple.

Bellerophon did as the seer recommended and slept the next night in the nearest temple of Athena. The goddess appeared to him in a dream and laid a golden bridle next to him.

According to some sources, this magical piece of tack was the first bridle ever invented.

Athena told the hero to make a sacrifice to Poseidon, who in some versions of the story is Bellerophon’s father as well as that of Pegasus, and to show the god the bridle as he did so.

When Bellerophon awoke, the golden bridle was laying next to him just as it had been in the dream.

On the following morning Bellerophon made the sacrifice of a white bull to Poseidon as Athena had instructed him to do and held up the bridle so the god could see it. He also built an altar to Athena to thank her for guiding him.

Following the seer’s visions, Bellerophon found Pegasus drinking at the Pirene spring outside of Corinth.

Without difficulty, he was able to mount the previously untamed beast. When he slipped Athena’s bridle onto the horse, it followed his instructions.

Pegasus flew his new master to the lands that had been all but destroyed by the Chimera. By flying at great speed, they were able to evade the monster’s fiery breath.

Bellerophon shot arrows at the great monster, but could do little harm to it. He got the idea to tip his spear with a piece of lead.

Flying in from above, he was able to use his spear to ram the lead deep into the Chimera’s throat. Unable to breathe out its flames, the Chimera was burned from within and died.

With the help of Pegasus, Bellerophon had cemented his status as one of the great legendary heroes of ancient Greece.

Today, the site of the legendary battle is still identifiable. The region of Lycia in modern day Turkey is known for its geothermal vents, which shoot eternal fire from the ground.

These methane-fueled flames were believed to be the remnants of Chimera’s destruction. They were so consistent that ancient sailors could use them to navigate the area’s coastline.

Pegasus’s adventures with the hero didn’t end with the fiery death of the Chimera, though. That was only the beginning of Bellerophon’s tale and the horse’s role in it.

After this challenge, Iobates ordered him to battle the Solymoi (Solymi), and when that was done, to take on the Amazones. When he had slain these, Iobates selected from the Lykians those most famous for their vigor, and instructed them to murder Bellerophontes in ambush; but when Bellerophontes had slain every one of them as well, Iobates, awestruck by his strength, showed him Proitos’ letter and said he would be honored if Bellerophontes stayed on with him. He gave him his daughter Philonoe, and, when he died, he left him his kingdom.

-Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 30 – 33 (trans. Aldrich)

Bellerophon was able to succeed on these quests only with the help of Pegasus. For example, in his fight with the Amazons he flew over the great warriors’ heads and pelted them with rocks from above.

The hero married the king’s daughter and was given reign over half the kingdom. He grew wealthy off the income of its rich vineyards and fruitful fields.

Bellerophon had at least three sons. His grandson, a younger Glaucus, fought in the Trojan War and relayed his grandfather’s story as an embedded narrative in the Iliad.

As the hero’s fame increased, however, so too did his ego. Eventually, Bellerophon grew too ambitious.

After so many great victories, the hero became convinced that he had earned a place among the gods. Mounting Pegasus, he urged the horse to fly toward the peak of Mount Olympus.

This arrogance angered Zeus, who sent a stinging gadfly after them. When the fly stung the winged horse it bucked and reared, throwing Bellerophon from its back.

The once-great hero fell to earth, landing roughly on the plains of Turkey. Blinded by a thorn bush when he fell, he lived out the rest of his life in obscurity and misery.

Other stories dispute Zeus’s role in Bellerophon’s fall. They say that the hero grew nervous and doubtful as he neared Olympus, believing it was not really the home of the gods.

When he looked down at the earth below him, he grew so afraid that he lost his grip on Pegasus. He fell to his death, just shy of reaching godhood.

This version of the story doesn’t admonish the hero for his arrogance, but rather for his lack of faith. By holding on just a little longer and not looking back at what he had left behind, he would have been rewarded with immortality.

The story of the rise and fall of Bellerophon was the subject of a lost play by Euripedes. The fragments that remain tell a tragic tale of the hero’s hubris and lack of faith.

In late antiquity, Bellerophon’s role as the tamer of Pegasus was replaced by Perseus. After killing the Gorgon, he immediately claimed mastery over her equine child.

The image of Perseus riding Pegasus through the sky endured, and the hero was remembered more vividly than Bellerophon.

While Pegasus and even the Chimera endured in modern folklore and media, the cautionary tale of Bellerophon was lost to the heroic ideal of Perseus.

The Horses of Olympus

Although Bellerophon had been thrown to the ground far below, either to his death or to years of suffering, Pegasus continued his journey to Mount Olympus.

When he arrived, Zeus welcomed the immortal beast. Pegasus was taken to the stables of Olympus to live a comfortable life among the gods.

When Pegasus arrived at Olympus, he joined a stable full of notable animals. In fact, the horses of the gods were well-known figures in mythology.

These immortal horses, the Hippoi Athanathoi, were mostly the descendants of the wind gods.

While the gods of the four winds were often depicted as men, they also took the form of horses. They were Boreas (the North Wind), Euros (the East Wind), Notos (the South Wind), and Zephyros (the West Wind).

In this form, as the Anemoi, they drew the chariot of the sky god Zeus. As horses, they were described by Plato as having wings on their backs, much like Pegasus.

The female counterparts of the four winds were the Harpies. Together, they produced many of the famous horses of the Olympians.

The immortal horses of the gods included:

- Arion – The horse owned by Heracles and later the hero Adrastos. He was the son of Poseideon and Demeter, and thus a half-brother to Pegasus.

- The Four Horses of Helios – Aethon, Aethops, Euos, and Bronte grew the chariot of the sun god.

- The Horses of Ares – Conabus, Phobos, Phloegeus, and Aethon pulled Ares to war. The four immortal steeds breathed fire.

- Lampos and Phaethon – The horses of Eos, the goddess of the dawn.

- The Horses of Erechtheus – The first king of Athens received two immortal horses as gifts from Boreas.

- The Twelve Horses of Troy – These were promised to Heracles, who laid siege to the city when the king of Troy refused to follow through on his promise.

- Xanthos and Balius – This pair of horses was lent to both Peleus and his son Achilles.

There were other mounts and chariot animals on Olympus. Apollo’s chariot was pulled by a pair of giant swans, while his sister Artemis had tamed four deer with golden antlers.

Despite these variations, however, horses were still the favored work animals of the Olympians. In the stables of the gods, Pegasus was in good company.

As part of the Olympian stables, Pegasus became associated with Zeus.

The poet Hesiod claimed that the great winged horse became the bearer of Zeus’s thunderbolts. Pegasus became one of the favorite and most trusted aids of the king of the gods.

Among the famous horses of the gods and heroes, Pegasus gave his name to an entire line of winged horses. Many of these pagasi were believed to be his offspring.

Several of these fantastic horses are associated with Poseidon.

In addition to his sea horses, the hippocampoi with their fish tails, many images of Poseidon also depict his chariot being drawn by a team of winged equines. He was said to have given a pair of such animals to the hero Pelops.

There was also an entire race of winged horses with great horns that were believed to be native to Ethiopia. With Pegasus himself being born in Africa according to the traditions of Medusa’s legend, they may have been related to him.

While all these winged creatures were known as pegasi, Pegasus was always singled out as a distinct creature from others of his type.

Eventually, Zeus was so pleased with the horse’s service that he placed him forever in the stars as a constellation.

Hippos, the Horse, was said to be his image forever flying through the night sky. It was often called by his name instead.

According to local legends, on the day of his transformation a single feather fell to the ground near the city of Tarsus in Turkey.

The arrival of the constellation Hippos in the sky marked the beginning of the spring rainy season in Greece. The seasonal storms brought Zeus’s thunder and made the springs associated with the winged horse run quickly.

Most ancient star charts pictured Hippos not as a complete horse, but as the upper half of a horse emerging from beneath the water.

Hippos came to be more commonly called by the name Pegasus. That constellation is still internationally recognized with that name today.

Most recently, the constellation Pegasus gained new fame as the site of the first confirmed exoplanet found in orbit around a sun-like star.

Pegasus in Art

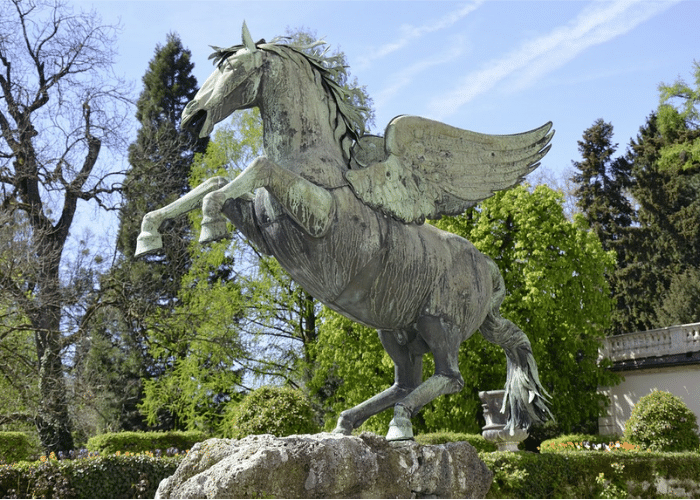

One of the reasons Pegasus remains such a well-known figure in Greek mythology is because he was a favorite subject of the period’s artists.

The exploits of the heroes were often illustrated in Greek pottery, mosaics, and frescos. The scene of Medusa’s death, including the birth of Pegasus, combined the favorite elements of a legendary hero and a terrible monster.

The further adventures of Bellerophon provided other opportunities to depict the winged horse in a scene of heroism. The beauty of the immortal horse provided a contrast to the disjointed ugliness of the Chimera.

Later, the two creatures became popular motifs on their own. The Chimera represented ferocity, while Pegasis and Bellerophon were a heroic pair.

The story of Bellerophon’s literal fall from grace was a favorite subject for allegorical works. In these, the flight of Pegasus toward Olympus represented the hazards of arrogance and hubris.

When Bellerophon was replaced by Perseus in the popular imagination, the heroism of his flight on Pegasus was only reinforced. The cautionary aspect of Bellerophon’s story was lost to the spirit of adventure and virtues of Perseus.

As part of Zeus’s bestial retinue, Pegasus and his offspring feature prominently in some of the god’s most majestic imagery. As the most recognizable of the immortal horses, Pegasus is identified with nearly all of the images of the chariots of the gods.

The Greek artists also depicted the horse as part of their cosmology for his identification with the constellation Hippos. Emerging from the water, the horse in the heavens retained its link to Poseidon and the magical waters of the Muses.

As the source of the Hippocrene, Pegasus was also identified with the inspirational artistic gifts of the Muses, making him even more popular with painters.

Pegasus took on a symbolism in art independent of his association with any particular myth.

The Greeks were fond of depicting hybrid animals and fantastical creatures. While many of these were monstrous or dangerous, like the Chimera that gave its name to such hybrids, Pegasus had a more positive characterization.

Despite being a hybrid of equine and bird characteristics, Pegasus was never described as a chimera.

The winged horse aided heroes, displaying bravery and loyalty against the foes of Bellerophon. His association with the Muses through his inspirational springs linked him to art, poetry, and creative pursuits

Pegasus was usually depicted as a white horse, a color associated with purity and light. While Bellerophon was denied entry to Olympus for his arrogance, the horse was deemed worthy and given great honors by Zeus.

While other hybrid animals, like the Chimera he helped to destroy, appear unsightly and grotesque, Pegasus was an image of grace. His power and agility in flight, as well as his beautiful form, inspired artists through the ages.

Even though he was born to one of the most fearsome monsters in legend, Pegasus became an undeniably beautiful symbol of virtue and goodness.

The Continuation of the Myth

Pegasus continued to be as popular after the Greco-Roman era as he was during it.

In heraldry, the winged horse was used as a symbol of physical and intellectual energy, and the use of that energy to move toward honor. Pegasus was commonly used as a crest in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Pegasus is today still seen on the coat of arms and flag of Tuscany. It was adopted after local resistance leadership used it as their emblem in WWII.

With the emergence of paratroopers in WWII, the British Royal Air Force began to use the silhouette of Bellerophon mounted on Pegasus as an insignia. While the insignia is no longer widely used, the selection process for the most elite parachute brigade is still referred to as Pegasus Company.

In honor of the heroism of British paratroopers during the Normandy invasion, a key bridge in the region is still known as Pegasus Bridge.

The mythical horse’s connection to water even lives on in the present day. Several ships of both the US and British navies are named for Poseidon’s offspring.

Pegasus has also been used as a corporate symbol. Several companies, most notably Exxon Mobile, have used the winged horse in their logos and advertising.

This use of Pegasus as a corporate logo has even left its mark on the urban world. Pegasus Plaza in Dallas, TX takes its name from the logo of Magnolia Petroleum, which later merged with Mobile and gave over its iconic logo.

Pegasus has become a common element in fantasy films and literature, particularly those that have other influences from Greek mythology.

C.S. Lewis, for example, featured flying horses along with Greek gods and nymphs in The Chronicles of Narnia. In comic books, Wonder Woman lives and fights alongside pegasi as the princess of the mythical Amazons.

In the Marvel universe, the winged horse retains a link to mythology, albeit not Greece. The Norse Valkyrie, a companion of Thor, rides a flying white horse into battle.

His association with the stars continues as well. Spaceships and galaxies in many works of science fiction, from Battlestar Galactica to Star Trek, bear his name.

Pegasus has become a frequently used element in anime and manga, in which it is common to combine creatures from many different world mythologies. In Western cartoons, the fantastical creature appears as the inspiration for characters in My Little Pony and several of the Walt Disney films.

In Fantasia, one of these films, pegasi appear alongside other hybrid creatures like centaurs in a fantastical dance. In the film Hercules he is, unlike in the original myths, a sidekick to that legendary hero.

Like Perseus, Hercules became associated with the flying horse in the popular imagination despite never riding him in the ancient myths.

Like their close relatives the unicorns, pegasi have become a part of fantasy and children’s media. While elements of the creature’s heroism and grace have remained, in entertainment the winged horse has become synonymous with fantastical, imaginative adventures.

The caution against flying too high like Bellerophon has been lost. Pegasus today is a creature of wonder and freedom who can take his rider as high as the stars.

Inspiration from Pegasus

Through the streams he created, the Pegasus of myth was connected to the Muses. This group of demigoddesses inspired artists, poets, and musicians to create innovative works of beauty.

Today, Pegasus continues to be linked to this spirit of beautiful innovation.

Artists continue to find inspiration in the form of the flying horse. Whether in fine art or comic books, Pegasus continues to be portrayed as a creature of unique beauty and grace.

The Greeks saw Pegasus in the stars when they drew out their constellations. Today, aircraft in both real life and fiction bear his name as they fly through the heavens.

To the ancient Greeks and to modern audiences, the image of the flying horse is one of wonder.

While his story may have begun with the death of a terrible monster, Pegasus became a lasting image of grace through the ages.