Greek

Medusa: The Monster Who Turned Men to Stone

Medusa: The Monster Who Turned Men to Stone

If you think you know the whole story of Medusa, think again – here’s everything you never knew about the mythical Gorgon.

The story of the monster Medusa’s death at the hands of the great hero Perseus is one of the most widely told myths from the Greek world. The image of the brave hero slaying the hideous beast endures in art, poetry, and song.

Medusa is remembered, more than anything else, for a face that was so hideous that one look at it would literally turn men to stone.

With monstrous features and snakes in place of her hair, she was a frightful creature that the Greeks believed could scare off even the most potent evil.

But there is much more to the legend of Medusa than just her beheading, and her legacy is far more complicated than that of any other ancient monster.

Lost in the telling are Medusa’s tragic origins and the unbelievable fate of her famous head.

There was a lot more to the Gorgon than just the snakes in her hair!

Medusa was Once Beautiful

Medusa and her sisters, the Gorgons, were the children of the primordial gods Phorcys and Keto.

Phorcys and Keto were also the parents of three other monstrous sisters – the Graeae. Their other siblings included the monsters Echidna, Scylla, and Ladon.

Keto was synonymous with sea monsters that her name was later used for the great serpents Poseidon conjured from the deep.

The earliest versions of the Gorgons connected them to sharp reefs and the storms that could drive ships onto them. They were associated with rocks, which when hidden below the surface of the water spelled disaster for ships passing by.

Their parents were early sea gods, predating the Olympians. The Graeae represented sea foam, while the other children of Phorcys and Keto were monsters of the ocean.

The Gorgons personified just one of the many dangers of the sea.

Stheno and Euryale, Medusa’s sisters, were immortal. Medusa was the only one of the three who could ever be killed.

Some stories say that there was one more unnamed Gorgon who was older than the others. She was killed by Zeus before he fought his father and the Titans for power.

Early accounts placed the Gorgons in a faraway place on the edge of night. Later stories had them living in Libya, a favorite setting for myths taking place outside of the Greek world and its cultural influence.

The earliest stories of Medusa said that she always had a terrible, inhuman form. But it didn’t take long for that to change.

As early as the 5th century BC there were mentions of Medusa being a beautiful woman in her youth. By the time of Ovid, she was one of the world’s great beauties.

According to him, as the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa was also the only one not born a monster. She had many suitors and was especially known for her beautiful long hair.

Medusa in this telling was separated from her monstrous family members and lived a more human life. Despite her family connection to monsters, she fit the mould of many beautiful young human women in mythology.

In these versions of her story, Medusa’s beauty would end up being her undoing. Like many pretty young women in Greek legend, she attracted the attention of a god.

Cursed by Athena

Even in the stories that came before descriptions of her beauty, Medusa’s tale was bound to the god Poseidon.

The god of the sea, like many of his peers, had frequent affairs with mortal women and minor goddesses.

The earliest version of the story describes Poseidon’s seduction of the Gorgon as taking place in a meadow filled with flowers. But later depictions tell a much darker tale.

In these, Poseidon not only took Medusa by force, but did so in a temple of Athena.

Greek mythology, like the culture that created, often made little distinction between seduction and rape. The gods often carried their lovers away or used deceit to get their way.

Kidnapping was a valid form of marriage in Greek mythology and women were often described as fleeing from or fearing the amorous gods.

Ovid, however, makes it very clear that Poseidon’s actions were not romantic.

Poseidon did not seduce or charm Medusa in the later myths. His actions were described as a forceful violation.

Poseidon and Athena were often at odds in the myths, and the disrespect of raping Medusa within her temple infuriated the goddess. As a virgin goddess, the act was particularly loathsome.

Unfortunately, as was often the case in the ancient world, the victim bore the brunt of the punishment.

Athena took her anger out on Medusa. She turned the young woman into a terrible monster.

Medusa’s famously beautiful hair was transformed into a writhing mass of snakes.

Once a renowned beauty, Medusa was now so horrifying that any man who looked upon her would be turned to stone. The fairest of the three Gorgons became the most hideous of them all.

In art, Medusa and her sisters had every terrifying feature the Greeks could imagine.

In addition to the serpents on their heads, they had tusks like boars, lolling tongues, and bulging eyes. Some images gave them wings, others a thick black beard.

Hesiod said they flicked their tongues, much like snakes. They wore snakes around their waists instead of normal belts.

Medusa’s body was often shown as abnormally large and disproportionate. Her large head and thick legs gave her a notably inhuman appearance that contrasted with the perfect forms of the gods and heroes.

Some versions of the story claim that Medusa’s sisters underwent the same change from beautiful to horrible, reconciling the disparity of showing only Medusa herself in that way. In this case Athena punished the sisters as well, although they had no involvement in the desecration of her temple.

The Gorgons were sent far from the civilized world to make their lair in a dark cavern. While Medusa was the only one whose gaze petrified men, her sisters killed and mutilated many.

Even after this terrible punishment, Athena had not finished the punishment Medusa.

The Death of Medusa

The most famous story of Medusa is that of her death at the hands of the great hero Perseus.

Perseus was the child of Zeus and the human woman Danae. King Polydictes wished to marry Danae but Perseus, by then an adult, opposed the union of his mother and the untrustworthy king.

Seeking a way to get her grown son out of the way, sent Perseus on a seemingly impossible quest.

He challenged the young man to kill Medusa and bring back her head.

Athena offered to help the hero on his quest. She gave her shining shield of bronze, the aegis, for protection.

Athena also told him where to find further assistance. After creating Medusa herself, the goddess seemed especially eager to aid the hero in the monster’s destruction.

The Hesperides, a sisterhood of nymphs, were guardians of a wondrous garden at the edge of the world. They had in their possession other items belonging to the gods that would help Perseus survive an encounter with the monster and her sisters.

His first mission was to find and defeat the Graeae. Only they knew the location of the Hesperides and their garden.

The three gray-skinned sisters of the Gorgons were born with only one eye which they shared between them. Passing their eye back and forth, one could be watchful at all times.

They also shared a single tooth, taking turns to eat their meals.

Perseus hid, waiting in the dark until two of the Graeae were passing the eye between each other. Quickly and deftly, he snatched the eye from their grasp.

Horrified, the Graeae demanded the return of their sight.

Perseus made a deal with the monsters. He would return their eye when they revealed to him the location of the Hesperides.

Some say he honored the agreement and left the watchful Graeae in peace. Others claim he threw the eye into the depths of Lake Tritonis.

Either way, the Graeae had shown him the way to the hidden garden of the Hesperides.

The nymphs gladly lent Perseus the treasures Athena had sent him for. The first was a strong bag in which to hold his trophy, the head of the Gorgon.

The second treasure was the magical helmet of Hades, given to him by the Cyclops in the Titanomachy. It had the power to make its wearer invisible.

The final treasure of the Hesperides was the winged sandals of Hermes.

Perseus was equipped to kill Medusa.

When he arrived at the sisters’ lair, the Gorgon was sleeping. Perseus used the same stealth he had practiced with the Graeae to sneak close.

This was where Athena’s bronze shield became invaluable.

Perseus could not look at Medusa or he would be turned to stone. Looking only at the monster’s reflection in the shining metal of the shield, he could creep forward without danger.

Perseus, therefore, with Athena guiding his hand, kept his eyes on the reflection in a bronze shield as he stood over the sleeping Gorgones, and when he saw the image of Medousa, he beheaded her.

-Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 36 – 42 (trans. Aldrich)

Medusa’s last scream in death woke the sleeping Gorgons, and the two sisters chased after the man who had killed her.

Now, Perseus took advantage of the treasures he had gotten in the garden.

Using the winged sandals, he was able to speed out of the cavern and avoid the angry monsters. Putting the helmet on his head kept them from seeing him, so they flailed blindly in their rage.

Perseus stuffed the head of Medusa in the bag and made his escape.

As Perseus fled the cave, however, he and the Gorgons were no longer alone.

The blood that spilled from Medusa’s severed head gave birth to two children – Chrysaor and Pegasus.

Little is known of Chrysaor, as he did not play a major role in later myths, except that he was later the father of a giant with three heads. But Pegasus, the winged horse, became a figure in many legends.

While a few tellings say that Pegasus helped Perseus escape, most agree that the mythical horse would not be tamed until Bellerophon fought the Chimera.

As Perseus used the sandals to fly over the sands of Libya, the droplets of blood that fell to the ground created enormous vipers. The creatures would remain common in North Africa forever after.

The death of Medusa had another immediate impact.

When Athena heard the cries of the Gorgons as they cried for their sister, she sought to emulate their mournful sounds. She invented the flute for this purpose.

The most common type of flute in ancient Greece had two bodies, a reflection of the two surviving Gorgons.

This was the last mention of Sthenno and Euryale in mythology. With their mortal sister gone, the other two Gorgons faded out of legend.

Her Head’s Continued Adventures

While the tale of her death at the hands of Perseus is one of the most famous moments in Greek mythology, it was not the end of Medusa’s story. In an unusual and macabre turn of events, Medusa’s death was only the beginning of her adventures.

When Perseus ran from the surviving Gorgons, he took their sister’s head with him as proof of his deeds. Even with the monster dead, Medusa’s true power lived on in her remains.

Some stories say that Perseus first used the Gorgon’s head while travelling back to his homeland. On his journeys, he came across the Titan Atlas holding the world on his back and used the head to turn him to stone.

This myth, a later addition to the story of Atlas, explained the creation of the Atlas Mountain range in North Africa. The power of Medusa’s head was so potent that it could petrify even the largest and strongest of the Titans.

Other tales say that Medusa’s head was used to destroy the great sea monster that threatened to devour Andromeda. Perseus killed the monster and later married the princess.

Although those details aren’t always included in Perseus’s legend, the writers do agree on what he did when he returned to his home in Greece. He turned his mother’s duplicitous suitor, Polydictes, to stone.

He did the same to many citizens who supported his would-be stepfather, creating the rocky terrain of the island of Seriphos.

Perseus later gave the head to Athena, who affixed it to her shield. Many depictions of Athena show the fearsome head of the Gorgon on her aegis.

Athena furthered her connection to Medusa by placing rows of snakes around her robes. While they didn’t have the power of the Gorgon’s head, they served as a frightening reminder of Athena’s curse.

Even this was not the end of the story for Medusa’s head, however. Throughout many Greek myths, it reappeared.

- When Perseus laid the head on a bed of seaweed, its magic caused the plants to harden. This created the first coral.

- Fighting the Ethiopian king Phineus, Perseus used the head against his enemies. Two hundred soldiers were turned to stone, including at least one of his own men who accidentally looked at the artefact.

- Phineus himself was the last of his army to be killed in this way. His petrification was slow and painful.

- Perseus later fought Dionysus and used the head against the god’s retinue of satyrs. The god held a diamond in front of his eyes to protect himself from the head’s curse.

- Ariadne, the wife of Dionysus, is said by a 5th-century writer to have been turned to stone in the war between her husband and Perseus. This story only appears in one source, however.

- Athena gave some of the Gorgon’s blood to the legendary surgeon Aesclepius. The blood could be used to destroy or restore and enabled him to bring people back from the dead.

- Athena also gave Heracles a bronze snake cut from Medusa’s head in a jar. He, in turn, gave the jar to Sterope to protect her city from invasion.

Medusa’s head, the gorgoneion, appeared constantly in Greek art. Athena used it to terrify her enemies and even a crude representation of it could strike fear into evil spirits and malicious beings.

The menacing face of the monster became a totem of protection.

Even a piece of Medusa’s head, like the one Heracles gave to Sterope, was enough to repel enemies and cause uneasiness even if it didn’t have the power to petrify.

Medusa wasn’t just mentioned again on earth. In the underworld, too, she appeared.

When Heracles was sent there, all the souls of Hades fled from him. Medusa’s spirit stayed and faced him down.

The hero drew his sword, prepared to fight, but realized she was nothing more than a hollow wraith.

Medusa is one of the spirits often said to lurk at the gates of the underworld, lifeless but unable to fully pass into the next realm.

Medusa in Late Antiquity

While the early Greeks depicted Medusa as truly monstrous, later artists began to change this image.

At the same time as writers began to show Medusa as a former beauty afflicted by a terrible curse, the face of Medusa underwent a similar transformation in art.

In sculpture, mosaics, and painting, the Gorgon began to lose her more beastly attributes. Her features softened.

The pointed tusks and extended tongue disappeared. Her face took a more traditionally human appearance.

Medusa began to look more like the woman she was described as in the texts.

By the time the Roman Empire was established, the face of Medusa was almost indistinguishable from that of any other woman. The only difference between Medusa and a human, or even a goddess, was the snakes that crowned her head.

Even in its more beautiful form, the gorgoneion was used as a symbol to ward off greater evils. It was often placed at the entrance to buildings, either in a relief carving or a floor mosaic, to prevent malicious spirits from entering.

Soldiers used Medusa’s head on their shields and armor, emulating the image of Athena, in an attempt to ward off death itself. The practice was so widespread that it is seen on the famous mural that depicts Alexander the Great’s battle against the Persians.

In this, the Gorgon was not only a symbol of protection. It tied the Macedonian kind directly to Greek heritage.

As the Roman world embraced Christianity and its texts, Medusa’s evil status was furthered. Judeo-Christian belief had always seen snakes as part of mankind’s fall from perfection and her serpentine hair made Medusa more recognizably evil than ever.

Medusa’s head was still treated as a frightening object, even when it was shown as being almost entirely human.

Images Today

The head of Medusa was the single most frequently used symbol in ancient Greek art. Because of this, it has become a widely-recognized icon.

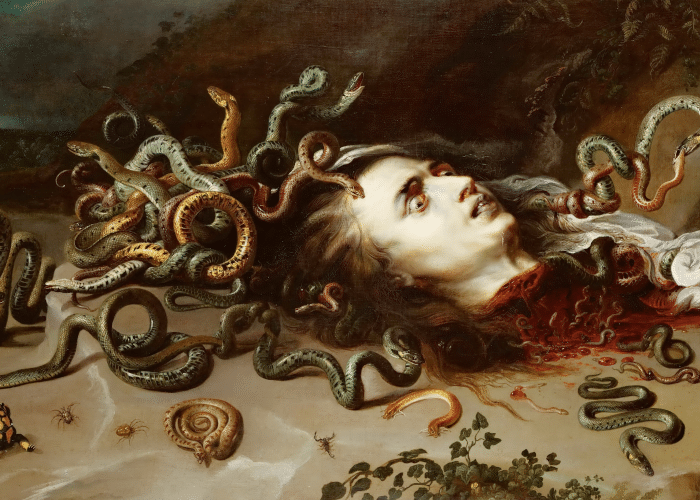

Artists of the Renaissance made the slaying of Medusa one of their favorite subjects in sculpture and painting. To them, the scene was a vivid illustration of the triumph of human ingenuity and heroism.

Perseus allowed them to recreate a male form that fit classical notions of perfection.

Medusa’s severed head provided the shock factor of gore and violence. The blood and gore that dripped from her neck were portrayed in graphic detail.

Additionally, the famous snakes on her head gave the artists a chance to display their skills with shape and texture. The loops and curves of a snake’s body have always been a favorite subject in art for this reason, and the figure of Medusa provided many of them for the artist to show off their skill.

It was after the French Revolution that the Gorgon herself began to take on more heroic connotations. Still portrayed as a human woman, albeit with an increasingly thick nest of snakes on her hair, Medusa became a symbol of the Jacobin faction.

The connection to the French Revolution and a famous story of beheading is obvious, but Medusa had also begun to be portrayed more sympathetically. Radicals saw the Gorgon herself as a type of revolutionary, taking power from the monstrousness that made her vulnerable.

This was in contrast to English liberty, which had been depicted as wise and powerful Athena. French liberty was not heroic, but it was not content to resign itself to victim hood.

The vision of Medusa as a victim of tyranny continues today.

The story of Medusa’s punishment following her rape by Poseidon has a much different meaning in the modern world than it did in Greek times. Her continued portrayal as a more feminine and human figure furthers this difference in interpretation.

When the feminist movement reexamined the legend, they came to a much different interpretation of Medusa than the Greeks subscribed to.

Being punished for her own victim hood made Medusa an emblem of the discrimination and violence faced by real women. In turning men to stone, however, Medusa’s anger reflected the rage women felt about these experiences.

Feminists reinterpreted Medusa as a woman who used her anger to avenge herself on the male gaze. They noted that in the myths there was never an instance of Medusa turning a woman to stone.

As art interpretation focused on the ways in which art represented the female body for the view of men, Medusa’s ability to punish men for looking at her became a powerful symbol.

Although men may have found her name synonymous with monotonousness, in Medusa women could find a reflection of their own fury.

Italian fashion company Versace took a completely different view of Medusa when they made her their logo. Completely devoid of monstrous connotations, they explained the use of the Gorgon’s head by praising its classical beauty.

In popular culture, Medusa has retained the duality between a sympathetic female figure and a dangerous monster. She frequently appears as a villain in comic foods, video games, and fantasy movies.

In these she takes two forms. Some versions of the character emphasize her feminine features, while she is given more attributes of a snake at times when she’s shown as particularly monstrous.

The modern take on Medusa often emphasizes her femininity by making her a seductive, sexual figure. From a monster to a passive victim, Medusa evolved into an example of the femme fatale archetype.

As a more sensual villain, Medusa’s snakes are, once again, linked to Biblical notions of sin and evil.

Medusa and the Gorgons are used as characters in stories with direct links to Greek mythology, but also in general fantasy and horror settings. Outside a specifically Greek context the monsters are now seen as a universal type.

In these roles, Medusa is more of an active monster than she ever was in Greek myths.

In the original story she was killed in her sleep with no chance of fighting back, and most of the deaths caused by her powers were when she was used as a weapon by someone else.

While her sisters killed men with their fangs and claws, Medusa’s power was passive. She didn’t even have to look at her victim – it was their gaze that caused their death.

In games and books, however, she actively attacks her enemies or lures them in with her sexuality. Unlike Perseus, the protagonists in these stories actually have to fight her.

Her powers are expanded in modern media. While she always retains the power to petrify her enemies, now she scratches, poisons, and grapples as well.

Medusa has survived in art as a popular motif in tattoo culture. Combining two traditionally popular images, that of a beautiful woman’s face and that of coiling snakes, she is chosen to represent both her modern power and her ancient demonism.

Her name is even used in politics, being invoked in unfavorable descriptions of female politicians. In that usage, the image of Medusa as a woman who can petrify men takes a more negative connotation than it does in feminist circles.

Despite reinterpretation by feminists and revolutionaries, Medusa’s name retains its connotations of monotonousness and deformity.

It is used, for example, in the scientific names of many animals to reference some particularly unsightly species and, of course, some snakes.

More than ever before, the popular view of Medusa is a complex one. The interpretation can vary by image, person, and context.

Medusa’s Complicated Legacy

The ancient Greeks saw Medusa as a particularly terrifying monster of legend.

They continued to believe this even after the development of the story that told of her punishment by Athena. To them, the initial punishment and the subsequent death were both justified.

It’s hard for a modern reader to accept this version of events. 21st century morals would see Medusa as a victim who was deserving of sympathy instead of punishment.

The myth of Medusa forces readers to confront an ugly truth – the victim isn’t always avenged.

The good guy sometimes doesn’t win and innocent people are sometimes harmed.

Medusa is seen by some today as the first example of victim blaming. While Poseidon walked free, Medusa was villainized for the crime of attracting his attention.

Rape was often a feature of Greek mythology, as much as the stories hide it in terms of seduction and marriage. And very often in mythology, as in life, the victim paid the price.

Zeus’s lovers were harassed by his jealous wife. Nymphs who fled the gods were cursed or turned into trees and flowers.

It was more rare for a victimised woman to be helped and avenged than it was for her to be punished.

Medusa’s punishment was more explicit and harsh than most victims in the Greek myths, but it was not entirely out of place.

The complicated nature of Medusa’s crime and punishment is something our culture still grapples with today.

From a vicious monster to a symbol of justified rage, the changing interpretations of Medusa’s nature reflect the changing morals and views of culture itself.