Greek

Amphitrite: The Queen of the Sea

Amphitrite: The Queen of the Sea

Poseidon’s wife was not one of the great goddesses of the Greek pantheon, but she proved that even a minor goddess can have a big impact. Discover the real truth about this amazing Goddess…

Discover the real truth about how Amphitrite went from being a simple nymph to the queen of the seas.

When the gods of Olympus took control of the universe from the Titans, they each found a wife to rule alongside them. While Zeus and Hades married well-known goddesses, however, Poseidon’s wife was from a far less lauded background.

Amphitrite was a Nereid, one of the fifty nymph daughters of an ancient sea god. Although she famously fled from his proposal, she eventually became Poseidon’s wife and queen.

While Greek mythology remembers Amphitrite as a nymph who rose to greater power through marriage, there is evidence that there might be more to the sea queen than meets the eye.

From her place as a mother goddess to the notion that she might be even more ancient than her husband, there is a lot to learn about the character of Amphitrite!

Amphitrite the Water Nymph

Amphitrite did not begin her story as one of the most important goddesses in mythology. Instead, she was just one of fifty sisters.

The Nereids were the daughters of Nereus, often called the Old Man of the Sea.

Their father was the eldest son of Gaia and her own son Pontus, a primordial god of the sea. Their mother Doris was the daughter of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys.

The Old Man of the Sea was an unusual figure in Greek mythology. Both Nereus and Proteus, who is sometimes called his brother, were identified as the shape-shifting god of the sea.

Most historians consider it likely that Nereus and Proteus both were ancient gods that predated the adoption of the Greek pantheon. While they were eventually supplanted by Poseidon as the ruler of the waters, they lived on in a few stories.

The Greeks rationalized this by having The Old Man of the Sea, as either of those gods, a more primordial figure who fell under the control of Poseidon when the Olympians took power. Historians, however, think it is likely that these pre-Greek gods were passed on from a time before the story of the Titanomachy and rise of the Olympian gods was ever conceived.

Perhaps as a sign of the changing belief in The Old Man of the Sea, Amphitrite is occasionally called an Oceanid instead of a Nereid. This made her a daughter of Oceanus, an established Titan, instead of the more elusive Nereus.

In either case, she was typically described as being the oldest of her sisters. There were fifty Nereids and three thousand Oceanids, giving her a large family in both stories of her origin.

Both groups of nymphs were minor goddesses of the seas. The Nereids were particularly associated with their father’s domain in the Aegean Sea.

This location put them in close proximity to Greek sailors and fishermen. While few would venture far enough abroad to encounter the more numerous but far-flung Oceanids, the Nereids were local to the waters just off the shore of Greece itself.

The Nereids were described as the most beautiful maidens in the world, a description common to many types of nymph. They were noted for their behavior, however, which Hesiod described as “beyond reproach.”

Marriage to Poseidon

Amphitrite stood out among her many sisters, however, in that she married the king of the seas. Although her marriage to Poseidon made her a far more powerful goddess than she would have been as a nymph alone, she initially rejected his advances.

Poseidon first saw her dancing with her sisters on the island of Naxos and was stuck with love for her. While he was an amorous god who had many mistresses among both nymphs and humans, he wished to make the beautiful Amphitrite his wife.

The nymph had no desire to be married though, so she fled from Poseidon’s advances. She hid near Atlas in the furthest reaches of the great river Oceanus.

She was eventually spotted, however, by Delphin. The dolphin god went to Poseidon to report Amphitrite’s hiding place.

In some versions of the story, Poseidon took Amphitrite by force and married her against her will. Other, gentler, legends however claimed that Delphin reasoned with the young goddess and persuaded her to marry Poseidon willingly.

It was said that dolphins were favorite animals of Poseidon because their god had helped him win his wife’s hand. Delphin himself was honored with a constellation to eternally commemorate his role int he marriage of Poseidon and Amphitrite.

Amphitrite and Theseus

One of the few stories in which Amphitrite often appears, albeit momentarily, is that of Theseus.

The great legendary hero of Greece was the son of her husband Poseidon and Aethra, a princess of Athens. Unlike Hera, however, Amphitrite seemed to have little animosity toward the children of her husband’s extramarital affairs.

Theseus is best remembered for killing the Minotaur, the monstrous human-bull hybrid that was imprisoned on the island of Crete. Taking a place among the Athenian youths being sent as a sacrifice to the man-eating beast, Theseus instead killed the monster and ended the horrible human sacrifices that had kept it alive.

He had not done so alone, however. Ariadne, the daughter of the Cretan king Minos, had fallen in love with the Athenian hero and helped him find his way out of the deadly Labyrinth.

With the Minotaur dead, Theseus prepared to leave Crete. Minos objected, however, when Ariadne intended to leave with him.

The king hurled insults at the young man, refusing to believe that he was the son of a great god. He pulled a gold ring off his finger and threw it into the sea, claiming that if Theseus really was the son of Poseidon he would have no trouble retrieving it.

Without pausing to even ask for his father’s help, Theseus jumped into the water. In moments, it became clear that he would have divine help in proving himself.

Theseus was surrounded by a pod of dolphins who led him down into the depths of the Mediterranean. They safely guided him to his father’s splendid palace beneath the waves.

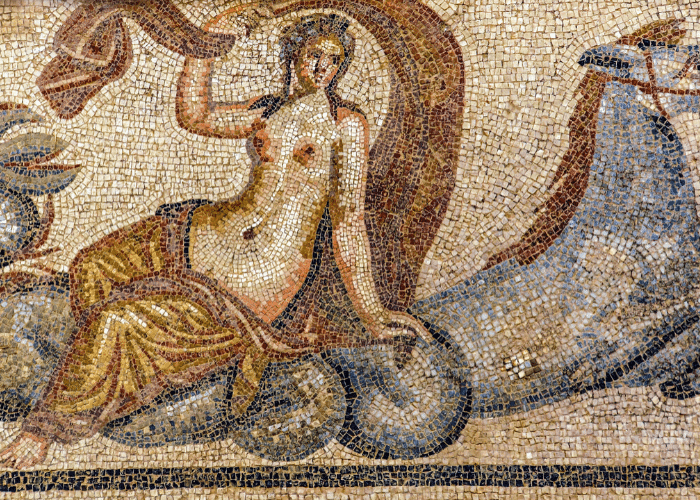

There he was awe-struck at the glorious daughters of blessed Nereus, for from their splendid limbs shone a gleam as of fire, and round their hair were twirled gold-braided ribbons; and they were delighting in their hearts by dancing with liquid feet. And he saw his father’s dear wife, august ox-eyed Amphitrite, in the lovely house

-Bacchylides, Fragment 17 (trans. Campbell, Vol. Greek Lyric IV)

She did not speak, but she gave Theseus the ring he had been sent to retrieve. She also wrapped a cloak of royal purple cloth around his shoulders and placed on his head a crown that she had received from Aphrodite on her wedding day.

Emerging from the water not only with the ring but also with his stepmother’s regal gifts, Theseus was able to prove beyond a doubt that he was the son of a great god.

The Mother of Sea Life

Amphitrite earned distinction as a mother goddess far beyond the kindness she showed for her husband’s mortal son.

She and Poseidon had four children according to most sources. They were:

- Triton – The sea god and only son of Poseidon and Amphitrite was usually depicted as a merman and served as his father’s herald and messenger. His role in the sea was similar to that of Hermes on Mount Olympus.

- Rhode – The goddess of the island of Rhodes married Helios, the sun god. Legend said that Helios was in the sky so when the gods divided the land between them he received no share. When Rhodes rose from beneath the water Zeus granted it to Helios and he married the nymph who lived there.

- Cymopoleia – She married the storm giant Briareos. She was the personification of the violent waves that arose during one of her husband’s strong storms.

- Benthesicyme – This name belongs to an African sea nymph. She married the king of Aethiopia, Enalos.

Amphitrite’s most numerous and well-known children, however, were not gods and goddesses.

She was the mother of all life in the sea.

Fish and shellfish were her children, as were seals. Even dolphins, which took the form of the god who had found her in hiding, were her children.

As the mother of all life in the sea, Amphitrite was one of the most prolific maternal goddesses in the Greek pantheon. While her divine children had little power or influence, the many sea creatures she gave life to made her a figure of fertility and maternal care.

Queen Amphitrite of the Sea

As Poseidon’s wife, Amphitrite’s position was elevated above that of the other Nereids. She became the queen of the sea.

In fact, Amphitrite herself was typically seen as a personification of the Aegean, the most important body of water for most Greek peoples. Myths and hymns often reference her more as the sea itself than as a specific character.

Amphitrite was most often pictured at her husband’s side. They shared his great chariot or she rode on the back of a dolphin or other sea creature.

In the Argonautica she was depicted caring for her husband’s sea horses. She unyoked them from their harnesses, symbolically releasing the waves that carried Jason’s beached ship back out to sea.

Rarely was Amphitrite shown acting outside of her role as Poseidon’s companion. When she was, however, she was a powerful force in her own right.

One writer from the 4th century AD hinted at this when he described a much older piece of art he saw in Greece. The painting described by Callistratus showed Amphitrite as “a creature of savage and terrifying aspect” whose flashing eyes inspired both awe and fear.

This one painting, however, is an outlier. Most often, Amphitrite was shown as little more than a beautiful companion to her powerful husband.

That may not have always been the case, however.

There is evidence that, at one point, Amphitrite was more revered as an individual goddess than she was in later Greek religion. While she was usually shown only in the company of her husband, never acting as an individual, a hymn to the birth of Apollo and Artemis shows her possible importance in some circles.

Leto, the mother of Apollo and Artemis, gave birth to her twins on the floating island of Delos. Hera did everything in her power to prevent the birth because there were many portents showing that Leto’s children, especially her son, would become more powerful than Hera’s own.

One sign of the importance of Leto’s labor was that she was attended by the most important maternal goddesses of the Greek pantheon. Like the birth of a human prince, the birth of Artemis and Apollo was legitimized through being witnessed by members of the nobility.

The most important maternal goddesses of Greece, with the exception of Hera, were on hand to act as witnesses to the birth of Zeus’s divine children. Rhea, Zeus’s own mother is among them.

The others are given different names but clearly represent the original Titan goddesses. The mothers of the gods were on hand to legitimize Leto’s children as being as important as their own.

Interestingly, Amphitrite was named among them.

This could be a simple nod to her importance as a mother goddess. It could also, however, be a relic of a time in which Amphitrite was much more important.

It is possible that Amphitrite was originally a primordial deity, like her father Nereus. While he and his brother ruled over all the seas, Amphitrite was the embodiment of the Aegean itself.

Over time, as the Olympian gods took the main roles in Greek religion, the Titans and primordial gods were relegated to more minor roles. If Amphitrite was once a primordial goddess of the sea, she was later reimagined as a simple nymph.

The marriage of Poseidon and Amphitrite, then, helped to connect the Olympian pantheon with the older traditions of pre-Hellenic religion.

Similarity to Thalassa

In fact, Amphitrite bears a striking resemblance to a much older goddess. Thalassa is more often attested by name in Roman-era works, but was occasionally referenced as early as the 6th century BC.

Historians suggest that the character has a much deeper past in pre-Greek legend. Like many of the primordial deities, she may have been a holdover from a more ancient religious tradition.

She was the consort of Pontus, the primordial god of the sea. Together, the two represented the elemental form of the sea itself.

Unlike the young and beautiful Amphitrite, Thalassa was most often depicted as a more matronly woman. She rose half out of the water with seaweed in her hair, often holding an oar.

Thalassa, like Amphitrite, was often invoked as the sea itself. When she spoke it was usually in a fable, often telling victims of shipwrecks not to blame her for their misfortune since it was the winds, not the flat sea itself, that gave birth to waves.

Also like Amphitrite, Thalassa was said to be the mother of all marine life. While the tradition of Olympus said Amphitrite gave birth to seals, fish, and dolphins, primordial legends said that Thalassa was their mother.

In each pantheon recognized by the Greeks – the primordial, the Titans, and the Olympians – the seas were ruled by a male and female couple. Poseidon and Amphitrite were the king and queen of the Greek seas, but they were preceded by Oceanus and Thetys the Titans, and by Thalassa and Pontus the primordial beings.

It is sometimes interpreted that many of the Olympic gods were natural evolutions of their primordial and Titan ancestors. Amphitrite the nymph queen may have been a new form of Thalassa, the older goddess of the sea.

Poseidon’s Wife Amphitrite

Amphitrite was a Nereid, a sea nymph, who married Poseidon. She initially avoided his proposal but was either found or convinced by the dolphin god Delphin.

Amphitrite became Poseidon’s queen, but played little tangible role in mythology outside of this role. She was most often shown beside him and surrounded by the many sea creatures she had given birth to.

She was a mother goddess in her role as the progenitrix of marine life. She also showed a sensitive, maternal nature in her recognition of Theseus as her husband’s son.

There is some evidence, however, that Amphitrite may have been recognized as a more powerful goddess at some point in the pre-Greek past. Her similarities to the primordial sea goddess Thalassa and inclusion in scenes like the birth of Apollo and Artemis may indicate that she was once the primary marine diety.