Greek

Atlas: The Titan Who Holds the Heavens

Atlas: The Titan Who Holds the Heavens

You probably know Atlas for holding the earth on his shoulders, but read on to learn more about this mythical Titan.

Even if you’re not familiar with the story of Atlas, you’ve probably seen his image. The muscular Titan holding a great globe upon his shoulders is a familiar figure.

If nothing else, you’ve seen his name on maps, books, ships, and games.

The legend of Atlas, however, goes far beyond holding the world on his shoulders. In fact, it wasn’t the world he was holding at all.

The full story of Atlas is one of defeat, suffering, and endurance. Out of all that, though, the legendary Titan grew into one of the most recognised figures in all of mythology.

From his part in the great war of the gods to how he helped Greece’s most famous hero, the story of Atlas is more than just holding a great burden!

Atlas and the Titans

Before the gods of Olympus took power, the universe was ruled by the Titans. Gaia, the mother earth, had given birth to this older generation of gods who were fathered by Uranus, the primordial god of the sky.

Atlas was one of the four sons of the Titan Iapetus. His mother was Clymene the Oceanid, one of the 3,000 daughters of the Titan Oceanus.

Atlas was the bravest and sturdiest of the brothers. Menoetius was considered the most handsome.

Prometheus was the cleverest brother of the four. His counterpart, Epimetheus, was kind but foolhardy.

Eventually, Gaia grew angry with her husband and urged her children to take their father’s power. Chronos was the only one willing to challenge Uranus.

The first king of the Titans was overthrown by his son. The younger deity took power as king and quickly became obsessed with keeping it.

He was so concerned with not losing his throne that he swallowed his own children at birth rather than risk one of them growing up to challenge him as he had done to his own father.

His wife, Rhea, hid her sixth child to spare the baby from this fate. Zeus grew up in secret and returned to free his siblings and end his father’s reign.

The resulting war against the first generation of gods is called the Titanomachy. For ten years the gods fought one another for control of the universe.

Two of Atlas’s brothers, Prometheus and Epimetheus, sided with the new gods on the promise of a greater share of power. Zeus vowed that anyone who joined his side would receive the recognition they had been denied under the tyrannical rule of the first two kings.

Atlas and Menoetius, however, maintained their loyalty to Chronos. With the majority of the Titans, they fought against Zeus’s coup.

Strong and brave, Atlas became the general of the Titans in the war. For a decade he used his might and fortitude to keep Zeus from claiming victory.

Ultimately, however, the new gods would win the Titanomachy. Gaia herself came to their aid, although she would later be bitterly disappointed by the treatment of her defeated children.

The majority of the Titans were imprisoned in Tartarus, the deepest part of the Greek underworld. Monstrous guards and heavy metal gates kept them imprisoned for ages.

As one of their leaders, however, Zeus and the new gods of Olympus decided that Atlas was deserving of a harsher fate. He would be singled out for a particularly grueling punishment.

The Heavens and the Earth

Many people believe that Atlas was given the task of holding up the earth, but in mythology his actual job was holding the sky.

According to the Greek view of the universe, the sky had a physical weight in the same way the earth or the sea did. It was a heavy place, a great vault.

To punish Atlas for his part in the Titanomachy, Zeus ordered him to hold the sky aloft.

The poet Hesiod described Atlas’s place of punishment as the place where the earth, the seas, and the underworld came together. It was where the darkness of night and the light of dawn met as they passed by one another.

In this liminal space, it would be easy for the sky to fall from its heights and crash into the other realms. Atlas was there to keep that from happening.

Described before as strong and determined, Atlas hoisted the weight of the heavens on his shoulders. There it would remain through the eons.

Poets talked about the great torment Atlas suffered. In Prometheus Bound, Aeschylus described the Titan as moaning in distress while his daughters sang lamentations for their father’s pain.

His knees bent under the weight and his shoulders chafed, but Atlas could never put down his burden.

Other versions of the myth have the sky held by a set of great pillars. In these, less common, stories Atlas is tasked with guarding the pillar and ensuring they did not falter.

In older versions of the story he held the pillar itself on his back. This variation became less common over time, though, and the most typical image of Atlas has him holding the sphere of the heavens directly on his shoulders.

Some ancient poets said that Atlas was not completely alone while he suffered. Through it all, he was tormented by a vicious dragon.

The tedious centuries of holding the sky on his shoulders did have one benefit, though. Atlas had plenty of time to think.

From his position he could see the ocean and the cosmos. He studied the movements of the water and the stars.

As time went on, Atlas recognized the patterns in these movements and how the moon and stars affected the sea.

Through these meditations, Atlas became one of the fathers of the sciences. He was the first to develop astronomy, and to devise how to use the position of the stars in navigation.

The story grew, eventually making Atlas himself responsible for moving the stars through the heavens. By spinning the great orbs that rested on his shoulders, he caused the constellations to move across the sky with the changing of the seasons.

Some said that he divulged his findings directly to humans. Others say that he told his secrets to Heracles, who brought them back to mankind.

Atlas and the Heroes

Atlas does not play a major role in many myths, trapped as he was in one position and place. But he does show up in two of Greece’s most famous legends – those of the heroes Perseus and Heracles.

Perseus was one of the great heroes of Greek mythology, famous for beheading the dreadful Gorgon Medusa and rescuing Andromeda from the sea monster.

Medusa had been a monster so hideous that one look at her could turn a man to stone. Although she was dead, the head that Perseus carried with him retained that terrible power.

On his adventures, the gods came to his aid. One of the gifts he was given was the use of the magic winged sandals of Hermes, the messenger of the gods.

Those sandals not only enabled him to fly, but they gave him the speed to outrun any opponent.

In early versions of the myth Perseus killed Medusa and, aided by the speed of the winged sandals, escaped her two enraged sisters. The next scene of the story had him encountering the princess Andromeda as she was chained to the rocks and about to be devoured by a monster from the sea.

Later tales, however, added a meeting with Atlas into the middle of Perseus’s legend. As Greek influence reached new parts of the world, new stories were invented to explain the things they found in foreign lands.

In these later additions to the mythology, dating from the 1st century BC and afterward, Atlas had become a shepherd. His lands were rich and bountiful, with flocks of sheep and an orchard of beautiful golden fruit.

These stories place his garden in Libya, a generic term in Greek literature for all of North Africa. Medusa’s lair was there was well, and Andromeda was a princess of Ethiopia.

Weary from his quest, Perseus asked the gigantic Titan for permission to rest there for a while before continuing on.

It was customary in Greek culture for a man to introduce himself by recounting his lineage and the deeds done by both himself and his ancestors. In this tradition, and hoping to earn favor, Perseus announced himself as a son of Zeus.

Atlas, however, had received a prophecy long before from Thetis that said that when a son of Zeus came to his lands the man would defile his orchard and take his prized apples for good.

Afraid that his orchard and lands would be destroyed, the Titan shouted threats at the hero instead of welcoming him. The argument quickly came to blows, the strongest of the Titans wrestling with the son of a god.

Even a hero as great as Perseus was no match for the strength of Atlas, though, and the man soon found himself grappled.

As a last resort, he shouted to the Titan that he had a gift for him. He reached into his bag and pulled out the severed head of Medusa.

The Titan was turned to stone the moment he looked at the Gorgon’s face.

The Greeks of the Hellenistic Age created this myth to explain the creation of the Atlas Mountain range in North Africa. Soaring high into the clouds, they said the mountains held the sky aloft just as their namesake had in life.

The detail of the golden apples plays a much larger role in another Greek myth, that of the twelve labors of Heracles.

Having been driven mad by Hera so that he killed his wife and children in a frenzy, Heracles was given twelve impossible tasks to prove himself worthy of redemption. Should he manage all of them, he would be cleared of his sins and welcomed to Olympus as one of the gods.

One of these tasks was to steal a golden apple from the garden of the Hesperides.

The Hesperides were four nymphs, sisters, who were in the service of Hera. The apples that grew in their orchard were said to give the gift of immortality to any man who ate them.

The Hesperides and their apples glowed with the rich golden light of sunset, the domain of the nymphs.

Stealing an apple would be no easy task. In addition to the nymphs, the garden was guarded by a dreadful dragon named Ladon. The apple trees had been a wedding gift to Hera from Gaia, and the queen of Olympus was intent on keeping it safe.

The garden was hidden in a secret location at the edge of the world, surrounded by high walls that no man could climb.

The first thing Heracles had to do in his quest for a golden apple was to find the garden. He began to search the world for a clue as to its whereabouts.

In his journeys, he happened upon Prometheus. The brother of Atlas had angered Zeus and, as punishment, was bound to a mountainside with unbreakable chains.

Prometheus could not help Heracles himself, but he told the hero where he could find assistance. The Hesperides were the daughters of his brother, Atlas.

As their father, Atlas would be able to enter the nymphs’ garden undeterred. Rather than having to fight his way past the great dragon, he would be free to pick an apple as he wished.

Following the directions Prometheus gave him, Heracles made his way to the place where Atlas held the dome of the sky.

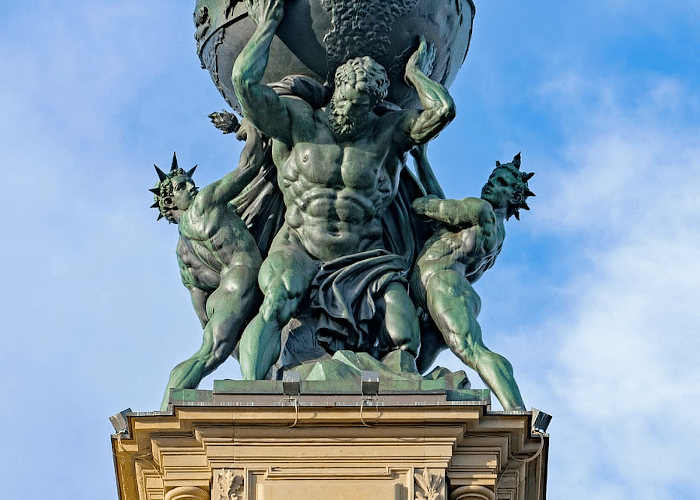

When the hero asked Atlas to go to the garden of the Hesperides in his place, the Titan was happy to oblige. The only issue was that he was stuck holding up the sky and, obviously, could not just simply leave.

Desperate to get the apple, Heracles offered to take over the Titan’s odious duty. After eons of bearing the enormous weight, Atlas was eager to take the hero’s offer.

Free at last of his burden, Atlas went to the garden and picked not one, but three golden apples. Many images of Atlas would reference this part of the story, putting his daughters’ three apples in his hand or at his feet.

When he returned, however, Atlas was not eager to give up his new freedom so quickly. He told Heracles, who was still holding the sky up, that he thought it was best if he delivered the apples for him.

Heracles sensed the Titan’s trap and knew Atlas had no intention of ever returning to take back his burden. He intended to leave Heracles holding his burden forever.

Herakles agreed, but by a trick gave the sphere back to Atlas. On the advice of Prometheus he asked Atlas to take the sky while he put a cushion on his head. Hearing this, Atlas set the apples down on the ground, and relieved Herakles of the sphere. Thus Herakles picked them up and left.

-Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 119 – 120

Atlas had tried to trick Heracles into taking his burden, but the hero had outwitted the Titan.

Some stories say that Heracles took pity on Atlas in the end, however.

Having delivered the golden apples and completed his labour, Heracles returned to the Titan. He erected the great pillars that were said to hold the sky, freeing Atlas from holding it himself.

At the Strait of Gibraltar, twin rock formations still bear the hero’s Roman name and are called the Pillars of Hercules. The two rocks, one in Spain and one on the African continent, mark the end of the Mediterranean and the furthest reaches of the Greek world.

On the same trip, Heracles had been able to free Prometheus from his unbreakable chains. Eventually, all the Titans would be freed from Tartarus as well.

None of this would have been possible if it had not been allowed by the king of the gods. Zeus had finally decided to end the punishments he had given out thousands of years before.

The Titan’s Children

The Hesperides were not the only children of Atlas. His offspring were not as numerous as those of many of the Olympian gods, but many were noteworthy.

Unlike Zeus or Apollo, Atlas did not have the freedom to chase down nymphs or appear to mortal women. He could not change his shape or carry his lovers off to distant islands.

However, he still managed to father several children through the ages.

In addition to the Hesperides, the children of Atlas included:

- The Pleiades – The seven sisters are remembered for the constellation of bright stars that bears their name.

- Maia – One of the most famous of the Pleiades, she became the mother of Hermes.

- Electra – Another of the Pleiades, her son by Zeus, Dardanos, became the ancestor of the Trojan people. She is sometimes called the lost sister because her grief after the defeat of Troy was so great that her star disappeared from thy sky.

- The Hyades – Sharing their name with a cluster of stars in the head of Taurus, they were nymphs of falling rain. The five stars of the Hyades became visible at the start of the Greek rainy season.

- Hyas – The only named son of Atlas, he was the brother of the Hyades. When he was killed by a lioness while fetching water, his sisters wept so much that they came to personify rainfall. Hyas was remembered in the stars as Aquarius, which was never in the sky at the same time as Leo.

- Calypso – Having fallen deeply in love with him, this nymph kept Odysseus captive for seven years as he traveled home from the Trojan War. She would not release him until commanded to by Zeus.

- Maera – Another star nymph, she was associated with the rising of Sirius, the dog-star, and the brutal heat of midsummer. Although legends of her death do not survive, she was one of the people seen by Odysseus on his journey to Hades.

Atlas’s wife Pleione was the mother of most of his children. The Pleiades were named for her, and the Hyades and their brother were probably her children as well.

Pleione is usually thought to be one of the Epimelides, the nymphs of sheep, and her name refers to the multiplication of flocks.

The link to Pleione may be one reason later myths of Perseus made Atlas a shepherd in charge of many animals.

Pleione’s grandson would continue the family’s connection to the flocks. Her grandson Hermes became, after stealing his half-brother’s cattle, the patron god of livestock and animal husbandry.

The daughters of Atlas were consistently linked to both stars and the sea.

As he held the heavens themselves, the stars of his daughters would have been part of his burden. As the inventor of navigation, it is fitting that his daughters were the stars sailors used to find their way.

The Sphere of Atlas

The image of the great Titan holding the heavens on his shoulders became a favorite subject for artists.

While much of the art itself has not survived to the present day, ancient writers describe the images of Atlas that they saw in the palaces and temples of their day.

A description of the great temple of Zeus at Olympia, where the first Olympic Games were celebrated, includes an image of Atlas during his visit from Heracles. According to the writer, this scene was depicted many times at Zeus’s temple.

A 3rd century painting at Naples supposedly showed the scene in vivid detail. The writer of the description describes the sweat on the Titan’s brow and the impression that he was panting, exhausted by the great work of holding the heavens.

Earlier Greek art showed the Titan in a variety of ways. Some pieces had him holding the base of a pillar that extended beyond the frame, others showed a large disc on his shoulders.

But the image of Atlas with a large, spherical orb held on his back is the most familiar to us. As the Greeks and later the Romans showed their skill with sculpting in stone, the globe balancing on the Titan’s shoulders became a way to visualize the story and show off the artists’ skills.

The way in which Atlas is typically shown in art is probably the reason many people assume he held the earth rather than the sky.

The usual depiction is a muscular man, stooped and kneeling with a great globe on his shoulders.

The Greeks imagined the heavens as a curving vault with mass and a physical form much like the ground. In sculpture and painting this was usually represented as a sphere, detailed with the swirling lines of the winds and heavenly bodies.

While we may think of the globe as a modern representation, Greek scholars recognized the spherical shape of the Earth as early as the 5th century BC. Aristotle noted the round shape of the planet in the 4th century BC and within a hundred years Greek mathematicians had calculated its circumference with surprising accuracy.

The vault of the heavens was a realm similar to the physical world and was shown in the same way. With its spherical shape and swirling clouds, the globe traditionally held by Atlas in art is easy to mistake for planet Earth.

The oldest surviving statue of the Titan is known as the Farnese Atlas. Dating from the 2nd century AD, the 7-foot tall marble statue is a Roman copy of an early Greek piece.

Atlas’s familiar orb is covered with low relief swirling patterns that, on close inspection, reflect nearly all of the constellations laid out by Greek cosmology.

Modern scholars examining the details of the carving believe it may represent the position of the stars as they would have been in the middle of the second century AD, perhaps giving a clue to the creation of the original Greek work.

Atlas provided more than just an opportunity to show the cosmos in Greco-Roman art.

The Greeks and Romans often depicted the ideals of the human form in art, and sculptors, in particular, prided themselves on their ability to capture the details of the human form. The figure of Atlas provided the perfect subject for showing the strained muscles and perfect proportions of an ideally muscular man.

The Farnese Atlas, as the oldest sculpture of the character, would serve as the template for images of the Titan in later times.

Arguably the most well-known modern example is the statue of Atlas in New York City’s Rockefeller Square. While this famous bronze Atlas bears an orb that has been stylized as a series of rings, his pose and physique are in keeping with the long tradition that began with Greco-Roman sculpture.

The God of Endurance

Atlas became a favorite subject in art for more than just his form.

Greco-Roman art, like the mythology that inspired it, often used legendary figures as personifications of human traits.

While the story of Atlas began with him being the enemy of the gods, he came to symbolize a very positive attribute. For the ages he spent under the burden of the heavens, Atlas became the personification of endurance.

Despite the physical suffering that Greek writers described him straining under, Atlas never faltered in his task. He never let the heavens fall.

Despite the one episode in which he tried to hand his burden off to Heracles, Atlas didn’t seem to fight his punishment either. While other Titans and demigods became enemies of the Olympians and plotted against them, Atlas was seen as stoic in carrying on his duty.

Atlas was forced to bear his burden alone, with no one to help him hold up the great mass of the heavens. His self-reliance became an admired attribute.

This image of endurance in the face of hardship appealed to Greek sensibilities. His suffering was invoked to inspire men to carry on in spite of hardship.

That spirit of strength and fortitude in the face of a seemingly insurmountable task helped the image of Atlas carry on into the modern world.

Even in medieval Europe, where many aspects of earlier pagan culture were frowned upon, Atlas appears in decorative carvings on the supports of pillars and archways.

Ancient temples sometimes feature columns in the shape of humans, and some of these have been interpreted as being of Atlas. Like Atlas, they are often depicted as though they are straining under the weight of the building.

This artistic tradition carried into more modern times. The world-famous Hermitage Museum features ten enormous atlantes at its entrance.

It is perhaps fitting that the mythological figure associated with extreme endurance has held up as a symbol for over two thousand years.

Our Many Reminders of Atlas

In today’s world, there are many reminders of Atlas and his famous punishment.

For both his association with the globe and his mythological study of the ocean his name lives on in cartography. A modern book of maps is called an atlas and many places around the world are named for him.

Atlas is still associated with strength and physical endurance. Famous bodybuilders and wrestlers have adopted it in the last century to link themselves with a legendary strongman.

Atlas has appeared in media, including comic books and video games. Whether as a superhero, a villain, or the name of a company his name is used in association with power.

In fact, many real world companies also carry the name Atlas. Whether to denote worldwide reach or the strength of their product, the Titan is used to market everything from books to air planes.

Fittingly for the being who held up the heavens, his name is also frequently used in astronomy. Atlas is a moon of Saturn, an asteroid detection system, and, tying in with the stories of his daughter, a star in the Pleiades.

From a symbol of defeat and punishment, Atlas as grown into a model of strength. Even people who have never heard his myth know his name.