Norse

The Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt is one of the most widespread motifs in European folklore. How did it originate and how do local versions of the Wild Hunt differ?

Throughout Europe, a belief existed in folklore that a group of spectral riders went forth at night on the hunt. The Wild Hunt was a portent of catastrophe and could bring death to those unlucky enough to witness it.

The Wild Hunt was typically headed by recognizable figures. While Odin is most commonly named as its head, local variations of the hunt name many gods, heroes, and even historical figures as leaders of the hunt.

While it is usually identified with Germany and Scandinavia, the Wild Hunt was believed to ride throughout most of Europe. Each country, and often each town, had its own version of what the hunt was and how to survive it.

So how did a piece medieval folklore become so widespread and what could have inspired the legend of the Wild Hunt?

The Legend of the Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt is a common motif in the folklore of many European cultures.

It is mentioned most often in Germanic and Norse regions. It is a part of the folklore of Britain, France, Spain, and parts of Eastern Europe as well.

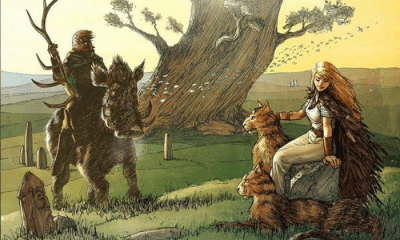

The Wild Hunt is usually depicted as a group of spectral riders led by a mythological figure. They are accompanied by ferocious hunting dogs, carrion birds, Valkyries, or elves.

In most cases, the Wild Hunt was seen as a portent of a catastrophe. It was said to appear before plagues, wars, famines, and the deaths of those who witnessed it.

In some traditions, those who saw the Wild Hunt could also be abducted by the riders. They would be dragged to the fairy realm or made to join the hunt themselves.

In Germany, the Wild Hunt is typically led by the god Wotan, although related female deities were sometimes identified instead. Sometimes it is lead by the spirit of a dead ruler, known as Count Hackelberg or Count Ebernberg, who is doomed to spend eternity riding with the hunt due to his misdeeds in life.

Werewolves are common in German depictions of the Wild Hunt. Rather than attacking bystanders, though, these monsters usually stole food and beer from the houses the hunt passed by.

These versions of the hunt were sometimes said to have a specific prey, usually a young woman. Sometimes this was an innocent victim, but in other cases it was a female demon.

In other accounts, the hunt did not chase prey. Instead, they fought amongst themselves and would kill any unfortunate person to happened to be nearby.

In Scandinavia, the Wild Hunt was typically led by Odin and was called the Asgard Ride.

The Asgard Ride was rarely seen. Its passage was recognized by the sound of Odin’s dogs barking, but no other noise could be heard.

Local legends offered advice for how to stay safe when the Wild Hunt passed. According to one story, Odin rode on a carriage pulled by oxen so throwing oneself to the ground would prevent a person from being hit by the yoke.

The French most likely adopted the Wild Hunt from the Normans. So many local variations developed that it is even known in parts of Francophone Canada, where the hunters fly through the air in a canoe.

An English account from 1127 claimed that several reliable witnesses, including monks, witnessed the Wild Hunt riding between Peterborough and Stamford over a period of nine weeks. Twenty or thirty huge riders went by on black horses and goats.

While early medieval accounts portrayed the Wild Hunt as demonic, later romances imagined it as a host of fairies. English leaders of the Wild Hunt included Nuada, King Arthur, Herne the Hunter, Wild Edric, and King Herla.

In a later legend from Dartmoor, the Wild Hunt was even led by Sir Francis Drake.

In Wales, the Wild Hunt is often led by Gwyn ap Nudd, the ruler of the Underworld. The trickster hero Gwydion is sometimes said to lead it instead.

The Irish Wild Hunt is typically associated with local mythology. Known as the Fairy Cavalcade, it is led by mythological heroes like Fionn mac Cumhaill or Manannan mac Lir.

Throughout Britain, the Wild Hunt is usually associated with local legends of hellhounds or black dogs. The hunt’s dogs are said to chase after sinners and the unbaptized.

Throughout Europe, the mythological characters of the Wild Hunt were often replaced by Biblical figures. Villains of the Christian tradition such as Herod, Cain, or the Devil were sometimes said to lead demons and the dead in a search for victims.

Stories of the Wild Hunt are often associated with the medieval era, but they remained a part of European folklore for many centuries. As late as the 19th century, rumors persisted that a king and his hunting party could be heard riding near Cadbury Castle on winter nights.

My Modern Interpretation

The term Wild Hunt was popularized by Jacob Grimm, who studied the folklore of Germany and related cultures.

Grimm identified the Wild Hunt strictly with Germanic traditions. He believed it was a remnant of earlier pagan traditions that had survived in superstition and folklore.

Grimm, however, viewed folklore through a nationalistic lens. He promoted the beliefs of early Germanic culture as part of his own cultural identity.

He therefore missed, or chose to ignore, the fact that the Wild Hunt was attested in many non-Germanic parts of Europe. It was known from Galicia to the Slavic countries in the east.

Jacob Grimm was probably not entirely wrong in identifying the Wild Hunt with Germanic traditions, but he failed to explain how the phenomenon became so widespread.

A possible explanation lies in both the figures associated with the Wild Hunt and the era in which it became well-known.

Throughout Europe, the Wild Hunt is typically led by mythological figures. These are often characters that were benevolent in the myths of their cultures, but in the context of the Wild Hunt become menacing and dangerous.

In Germany and Scandinavia, for example, the hunt is led by Wotan/Odin. While that character could be dangerous in his original mythology, he takes on a more demonic role as the leader of the Wild Hunt.

Grimm may have been correct in his belief that, to some extent, the Wild Hunt originated in Germanic paganism. It may have been inspired by Odin’s army in Norse mythology, the Einherjar.

These souls were gathered from battlefields by the Valkyries to fight and feast in the god’s hall, Valhalla. At Ragnarök, the Einherjar would ride forth with Odin to battle Fenrir, the monstrous wolf.

In Norse culture, riding to war after death was seen as a noble aspiration. The Wild Hunt, however, did not emerge in the Norse era.

Instead, the Wild Hunt appears after Christianity had taken hold throughout Europe. This religion had a much different interpretation of ancient myths.

In fact, it was well attested that Christian monks and missionaries sometimes intentionally demonized mythological figures to discourage folk beliefs from holding onto them. It is possible that the Wild Hunt developed from the Christian association of paganism with the demonic.

Odin’s warriors, who were seen as heroes by the Norse, were transformed into dead and ghostly riders. Rather than threatening the monsters who emerged at Ragnarök, they became a threat to Christian people.

If the Wild Hunt was based on a Norse and Germanic god, however, how did it spread so widely?

It is noteworthy that records from as early as the 11th century mention the Wild Hunt. The fact that these were written, particularly by Christian monks makes it more likely that the tale would have spread.

The medieval era is often thought of as a time of cultural stagnation, but it was also a time when the influence of the Christian Church spread ideas throughout Europe.

It is possible that the Wild Hunt was one of these ideas. Once the image was popularized in one region, likely Germany, it quickly spread.

This was aided by the fact that figures from Germanic paganism were already well-known. Odin was worshipped was Woutan by the Anglo-Saxons and was known in parts of the Slavic countries as well.

In areas where Odin was not known, local figures replaced him as the leader of the Wild Hunt. In France, for example, the Normans were familiar with Odin but locals changed the identity of the hunt’s leader to something more familiar.

In places where earlier beliefs were not as strongly demonized, the Wild Hunt tended to take on a less threatening nature. In Ireland, for example, the gods had been reduced to fairies so the Cavalcade was far less demonic.

In time, many local versions of the Wild Hunt lost their connection to pagan religion. The leader of the hunt was continuously changed to include characters that the people of the area recognized as threatening or otherworldly until eventually even historic figures like Francis Drake or Theodoric the Great led the hunt.

According to one scholar, the idea of the Wild Hunt spread in part because it reflected a very basic and universal idea – the connection between life and death.

The Wild Hunt was imagined as an even in which the line between life and death was blurred. Like the celebration of Halloween or 18th century seances, this blurred line has always held a fascination and been a major part of both folklore and religion.

In Summary

The Wild Hunt is one of the most common elements of European folklore. Although often associated with Germany and the Nordic countries, versions of the Wild Hunt were said to exist in Eastern Europe, Spain, England, Wales, France, Ireland, and even Canada.

Usually led by a mythological figure or king, the Wild Hunt was a threatening, spectral party. It was typically seen as an omen of disaster and could even bring death to anyone unfortunate enough to see it.

While local variations existed, the most common version of the Wild Hunt was led by Odin, or Wotan in German.

According to Jacob Grimm, this was evidence that the Wild Hunt was a surviving remnant of Germanic pagan belief that had carried over into the modern era. This does not explain, however, how versions of the Wild Hunt spread to non-Germanic areas.

Grimm may have been partially correct in assuming the hunt to be Germanic. The spectral riders may have been inspired by the warriors of Valhalla who rode forth with Odin at Ragnarök.

Rather than being a surviving aspect of ancient belief, however, it is likely that the Wild Hunt was inspired by Christian-era distrust of paganism.

Pagan gods and heroes were often reimagined as demons or villains by Christians. It is easy to see how Odin’s dead warriors would be seen as evil or threatening.

Because Odin/Wotan was so widely known in Europe, the imagery of the Wild Hunt would have been able to spread more quickly. When regions that did not have a Germanic religious tradition heard or read about the hunt, they substituted their own local gods and kings and the leader.