Aztec

Huitzilopochtli: The Mexican God of War

The people of pre-Colombian Mexico believed that the sun was in constant conflict with the night sky. Read on to find out more about Huitzilopochtli and the impact he had on Aztec culture.

According to Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli was the god of the sun. He also served as a god of war. In some traditions he was also one of the world’s creators.

These domains made him one of the foremost deities of the Aztec pantheon. To many people in the culture, however, he was a god of even greater importance.

One of the major tribes in the Aztec culture was the Mexicas, the people who gave the country of Mexico its name. To the Mexica people, Huitzilopochtli was the patron god who guided their people to central Mexico.

Huitzilopochtli was an ancient god whose influence is still felt throughout Mexico today. From the city he founded to the sign he sent his people, the Aztec god of the sun and war continues to have an impact on the country he was once worshipped in.

The First Birth Narrative of Huitzilopochtli

The most well-known story about the origins of the warrior god was as the son of Coatlicue. The mother goddess had four hundred sons and a daughter, Coyolxauhqui.

Coatlicue was cleaning in a temple one day when a ball of feathers drifted into her. She became pregnant as a result of this supernatural encounter.

Her children were furious when they discovered that their mother was going to have another child. Feeling that she had brought shame to their family, they attacked her.

In some versions of the legend, Huitzilopochtli was born as his mother was struck and was able to save her. In most, however, he was born at the moment of her death.

Huitzilopochtli was born fully grown and dressed in armor. He attacked his siblings, avenging his mother in his first act.

Coyolxauhqui, the leader of the siblings, was beheaded and her body thrown from the mountaintop they lived on. The four hundred brothers fled in a panic, scattering across the sky.

Huitzilopochtli became a sun god who was always at odds with his siblings. His sister, who became the moon, and their brothers, the stars, hated him.

This explained, in the Aztec view, why the sun chased the moon and stars across the sky. To them, it was Huitzilopochtli trying to destroy the siblings who had killed his mother.

Those siblings, however, posed a continual threat. If Huitzilopochtli was weakened, they would be able to defeat him and bring eternal night to the world.

Sacrifices to Huitzilopochtli kept him strong so he could continue to overpower Coyolxauhqui and their brothers. Without sacrifices, the Aztecs believed, the world would fall into total darkness.

The God of the Mexicas

The mythology of Huitzilopochtli changed over time, however.

In some places, this birth story was replaced with another. This second story made him the brother of Quetzalcoatl and the twin Tezcatlipocas.

In this origin myth, he had a hand in creating fire, the first humans, and the land. He was one of the world’s most important creator gods instead of just the god of the sun.

This change in mythology was due to the changing political landscape of Mexico.

While we think of the Aztecs as a single culture, they were actually a confederacy of several individual states. While their languages and religions were closely related, each group had their own distinct differences.

Huitzilopochtli was the patron god of one of these groups, the Mexicas. They were the rulers of the empire that would later be known as Aztec.

When the Mexicas united with other tribes, specifically the Nahuas, they attempted to create a more unified mythology. By combining their religious traditions, they hoped to strengthen their alliance.

Tlacaelel, the architect of this unification, put the god of the Mexicas as the same level as Quetzelcoatl, one of the principle Nahua gods. The legend was reworked to make them siblings and equals in the creation myth.

The later view of Huitzilopochtli, therefore, is distinctly Aztec. Although he was originally a god of the Mexicas, he became a god of the entire culture.

Huitzilopochtli’s Temple

The center of Huitzilopochtli’s cult was in the capital city of Tenochtitlan. The Templo Mayor, the largest and most prominent building in the city, was dedicated in part to him.

Huitzilopochtli shared the temple with Tlaloc, the god of rain. The sun and rain together were essential to preserving life.

Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc represented complementary opposites. As the rain god, Tlaloc was a deity of fertility and abundance. Huitzilopochtli represented heat and war.

In the structure of the great Templo Mayor, therefore, there was a temple for each god within the larger pyramid. Huitzilopochtli’s was on the south side of the platform while Tlaloc’s was to the north.

Because sacrifices were necessary to keep Huitzilopochtli strong enough to keep his place in the sky they played an important part in the daily life of Tenochtitlan.

According to the Spanish conquistadors who saw Tenochtitlan in the 16th century, sacrifices at the pyramid were a near-daily event. Huitzilopochtli himself, however, had just one specific holiday.

Sacrifices, however, may have taken place at other times. While their accounts were often sensationalized, archaeologists have found evidence of sacrifice in both art and human remains.

Sandoval, Francisco de Lugo and Andreas de Tapia were standing with Pedro de Alvarado each one relating what had happened to him and what Cortes had ordered, when again there was sounded the dismal drum of Huichilobos [Huitzilopochtli] … and we all looked towards the lofty Pyramid where they were being sounded, and saw that our comrades whom they had captured when they defeated Cortes were being carried by force up the steps and they were taking them to be sacrificed. … We saw them place plumes on the heads of many of them and with things like fans in their hands they forced them to dance before Huichilobos and after they had danced they immediately placed them on their backs … and with some knives they sawed open their chests and drew out their palpitating hearts and offered them to the idols that were there, and they kicked the bodies down the steps …

-Bernal Diaz del Castillo, True History of the Conquest of New Spain (1568)

The Templo Mayor was dedicated to two gods, but it was also constructed to reflect Huitzilopochtli’s myth.

According to the legend of his birth, Huitzilopochtli was born on Coatepec, or Serpent Mountain. The Templo Mayor, the great pyramid, was decorated with snakes.

When Huitzilopotec killed his sister, he threw her body down the side of Serpent Mountain. Each sacrifice performed at the summit of the pyramid reenacted this event when the body of the victim was pushed down the stairs.

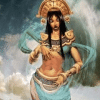

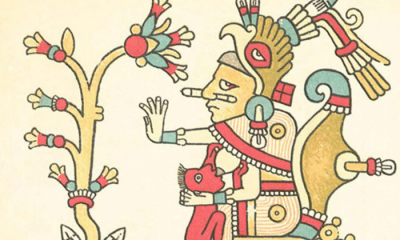

The Iconography of the War God

Like other gods, Huitzilopochtli can be identified in art through a variety of attributes. These included:

- Hummingbird: Hummingbirds were associated with warriors in Aztec culture. Huitzilopochtli was shown either as a hummingbird or as a human figure with blue feathers on part of his body.

- Xiuhcoatl: Huitzilopochtli carried the mythological blue serpent like a weapon. At times, he was instead shown with a snake-shaped staff to represent the fire-creating serpent.

- Shield: He often carried a shield decorated with a ball of eagle feathers, a reference to the story of his birth.

- Stripes: Many Aztec gods had unique coloration. Huitzilopochtli was typically shown with a yellow and blue striped face.

The most consistent part of Huitzilopochtli’s iconography was his hummingbird helmet. The blue-green headpiece was adorned with feathers and sometimes shaped to resemble the bird.

Hummingbirds had a unique symbolism in mesoamerican cultures. The brightly-colored birds were associated with warfare.

The Mexicas believed that warriors became hummingbirds after death. Because of this, the iconography of many gods included references to hummingbirds.

Some scholars believe that there is a rational explanation for this association.

Although not technically hummingbirds, a similar-looking species that is native to Mexico hibernates in trees during the winter. One theory suggests that the sight of these birds seeming to come back to life in the spring created the association with reincarnated spirits.

There is also a belief that these birds could have inspired Huitzilopochtli’s birth story.

Although Coatlicue’s conception was seemingly miraculous, her children believed it brought shame upon her. Interpreting the ball of feathers as a warrior, however, would make Huitzilopochtli the product of an affair rather than a miracle.

Huitzilopochtli’s Sacred City

When the tribes of Mexico agreed to join together, the Mexica city of Tenochtitlan became its capital. While power shifted at times, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived Tenochtitlan was the center of Aztec culture.

According to the Mexicas, Huitzilopochtli had founded both the city and the Mexica tribe.

Several Mesoamerican tribes, including the Mexica, claimed to have originated in a land they called Aztlan. While some sources described Aztlan as a paradise, others said that the people were oppressed by tyrannical rulers.

Huitzilopochtli ordered one group of these people to leave that land. He renamed them the Mexica and told them to never use the word Aztecah to describe themselves again.

The god left the people in the care of his sister Malinalxochitl, the goddess of desert creatures. She founded the city of Malinalco.

The people were unhappy with Malinalxochitl’s rule, however, and called to Huitzilopochtli to help them leave her city. He put his sister into a magical sleep and led the people away from her city.

Malinalcochitl was furious when she awoke and realized that she was alone. She gave birth to a son, Copil, to take vengeance on her brother for stealing the Mexica from her.

Huitzilopochtli tried to avoid a confrontation with his nephew, but eventually had no choice but to fight him. He killed Copil and threw his heart into a lake.

Many years later, the Mexica had not found a place to make their home. Remembering the lake, Huitzilopchtli told his people to find Copil’s heart and build their city there.

He told them that he would give them a sign. The heart would be marked by a great eagle holding a snake and sitting on top of a cactus.

The people found the eagle on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. There, they founded the capital city of Tenochtitlan.

The city is still a capitol, known today as Mexico City. The eagle, serpent, and cactus that Huitzilopochtli told the people to look for is on the flag of modern Mexico.

The Heaven of the God

Like many other Aztec gods, Heuitzilopochtli was also a god of the dead.

Many Aztec deities ruled over their own realm of heaven. Each took different people to their lands after death.

According to one Spanish ethnography in the 16th century, fallen warriors were taken to Huitzilopochtli’s realm after they died. They traveled in the form of hummingbirds.

The Florentine Codex claimed that Huitzilopochtli shone with such a bright light that the warriors had to use their shields to cover their eyes. These shields were made with arrow slits through which allowed the warriors to peek through to see a glimpse of the god.

Looking directly at the shining god could be perilous, though, so only the bravest fighters got a clear look at him.

While it would seem logical for a god associated with war to take fallen fighters to his realm, they were not the only dead people he took. The Florentine Codex also said that women who died in childbirth would be taken to Huitzilopochtli’s palace.

Childbirth was considered by many cultures to be the feminine equivalent of battle. Like battle, death was not the hoped for outcome but was seen as an honorable end when it did happen.

These women joined the men who had died while fighting to serve Huitzilopochtli in his heavenly palace.

The Founding God Huitzilopochtli

In the mythology of the pre-Colombian people of Mexico, Huitzilopochtli was one of the major gods.

He was originally the patron god of the Mexica people. They believed that he had led them to Lake Texcoco to found their city, Tenochtitlan.

To show them where to build their home, Huitzilopochtli told them to look for an eagle holding a serpent while perched on a cactus. This image of the founding of what would later be Mexico City is still featured on the country’s flag.

To them, he was the god of the sun and of war. When they united with other cultures in the region, he also came to be seen as a creator deity.

Because he was so important, particularly in Tenochtitlan, his temple was part of the largest religious complex in the city. The Templo Mayor was the site of dramatic sacrifices meant to help him prevail in his constant battle against eternal night.