Greek

Daphne: The Nymph of the Laurel Tree

Daphne: The Nymph of the Laurel Tree

You’ve probably heard her name but how well do you know the story of Daphne, the nymph that was turned into a laurel?

The name Daphne is a familiar one to many people. It’s still in common use today, even though it comes from an archaic language.

In Greek mythology, Daphne was a free-spirited nymph who rejected the idea of marriage for a life of simple pleasures.

All that changed, however, when a single arrogant remark started a feud between the gods Apollo and Eros.

The innocent nymph was caught in the middle, a victim of pride and vengeance.

From her origins as a river spirit to her remembrance as a symbol of Apollo’s guilt, here is the sad story of how Daphne was turned into a laurel tree.

The Many Versions of Daphne

The story of Daphne has several versions in Greek mythology. Although all arrive at the same point, they give very different origins for the character.

This suggests that the story was an old one that long predated the time when the myths were written down. The different versions of Daphne reflect the local changes made to the story as it was passed on through oral tradition.

One of the most widely known versions said that Daphne was a naiad.

This class of nymphs were the spirits of waterways. They were associated with the many small streams, well, and brooks that dotted the landscape.

She was said to be the daughter of a river god, although local traditions placed the river in different places. Arcadians claimed she was the daughter of the river Ladon, while Thessalonian tradition named the river god as either Peneus or Peneios.

The inclusion of a branch of laurel grown in a special grove in Thessaly in the festivals at Delphi suggests that this version of the story is the oldest, or at least the most widely recognized.

Depending on the source, her mother was either another nymph or Gaia, the mother earth, herself.

While the most commonly told versions of the story claimed Daphne was divine, the earliest written account says that she was a mortal. She was the daughter of Amyclas, a mythical king of Sparta.

In this version, Apollo began as Daphne’s defender. She had sworn a view of chastity and spent her time hunting with a group of maidens, but a boy named Leucippus disguised himself as a girl to get close to her.

Apollo exposed the deception and the girls killed Leucippus, but then he, too fell in love with Daphne. From that point, the story remains largely the same as in other versions.

The version of the myth seems to have been less popular than the ones identifying her father as a river god, and it fell almost entirely out of favor when the scholars of Renaissance Italy began reintroducing ancient mythology to their culture.

Whatever her origins, all versions of Daphne’s story revolve around her pursuit by Apollo and the transformation she undertook to avoid him.

The Arrows of Love

According to Ovid, Daphne’s tragedy began when Apollo insulted Eros.

Both gods were associated with archery. Apollo and his twin sister, Artemis, were said to have invented the bow while Eros used his to make people fall in love.

In Ovid’s version of the tale, based on earlier Greek accounts, Apollo was dismissive of Eros’s skills. He said the bow was a man’s weapon and Eros was just a boy.

Eros was known for weaponizing love, though. The god had a long history of using his arrows to get revenge on people by making them fall desperately in love with poor matches.

He had also proven before that he had no qualms against directing his arrows toward his fellow Olympians.

After Apollo’s insulting comment, Eros flew away to a nearby hillside. From his position above everyone else, he shot two arrows.

The first was a golden arrow that hit Apollo. The god was instantly overcome with love for Daphne.

The nymph had never shown any interest in marriage. Instead, she emulated Artemis and spent her time running and playing games with a company of girls in the forest.

A golden arrow from Eros’s bow could have changed that, but the mischievous god of love had other plans.

The arrow aimed at her was tipped with lead. Rather than love, it inspired revulsion.

Already opposed to the idea of marriage, Daphne became more devoted to avoiding intimacy with the opposite sex. Apollo particularly, thanks to the magic of Eros, was hateful to her.

Daphne’s Metamorphosis

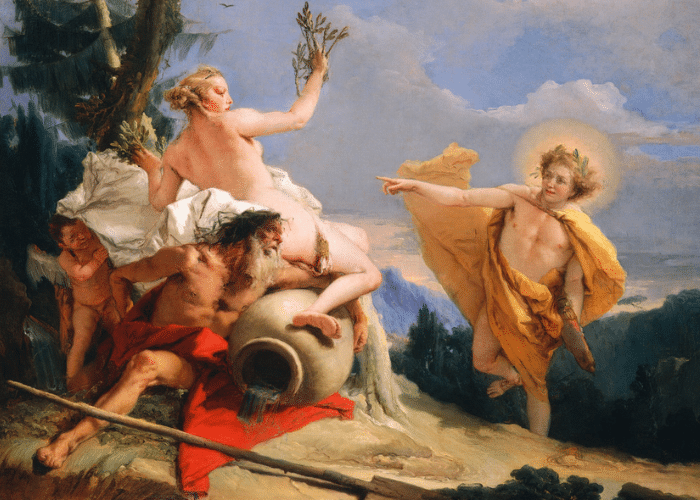

Overcome with love, Apollo chased after Daphne. She, however, was repulsed by him and ran away.

Apollo chased after her, completely blinded by the love that Eros had inspired. While the nymph was wild and dishevelled, he saw her as a perfect image of beauty.

As the two ran through the woods, Apollo tried to convince her to stop.

He called out to her that he worried she would hurt herself while racing through the forest. She could be scratched by briars or suffer a fall and he would not be able to forgive himself if he was the cause of her pain.

He thought she had mistaken him for a rough peasant and did not know who he was, so he shouted out that he was the lord of Delphi, the god of music, and the son of Zeus.

He even lamented that, even though he was the god of healing medicine, he could not cure himself of his love for her.

He tried to assure her that he meant her no harm and would not hurt her, but Daphne paid no attention to his protests. Already hateful of the idea of marriage, the lead arrow made her even more disgusted by the god that pursued her.

Daphne ran, according to Ovid, like a hare being pursued by a hunting dog. She grew more panicked and desperate the farther she went.

Daphne began to grow tired. Although she was used to running through the forest and was driven by fear, Apollo continued to grow closer and closer to catching up to her.

Apollo, however, was driven by love. The insatiable desire caused by Eros’s shot pushed him to run faster than Daphne could hope.

As he gained on her, Daphne knew she would soon be overtaken and she cried out for help. Some versions of the story said that she called out to Gaia, but most, like Ovid, said that she ran for the banks of the river and called to its god, her father.

Daphne begged whatever power would listen to take away her beauty and keep her safe from Apollo.

Scarce had she made her prayer when through her limbs a dragging languor spread, her tender bosom was wrapped in thin smooth bark, her slender arms were changed to branches and her hair to leaves; her feet but now so swift were anchored fast in numb stiff roots, her face and had became the crown of a green tree; all that remained of Daphne was her shining loveliness. And still Phoebus loved her; on the trunk he placed his hand and felt beneath the bark her heart still beating, held in his embrace her branches, pressed his kisses on the wood; yet from his kisses the wood recoiled. ‘My bride,’ he said, ‘since you can never be, at least, sweet laurel, you shall be my tree. My lure, my locks, my quiver you shall wreathe.’ . . . Thus spoke the god; the laurel in assent inclined her new-made branches and bent down, or seemed to bend, her head, her leafy crown.

-Ovid, Metamorphoses 1. 452 ff (trans. Melville)

Daphne had escaped from Apollo, but was lost to the world forever. She had been transformed into a laurel tree.

Her metamorphosis was complete just as the god caught up to her. He reached to embrace her, but it was already too late.

In the last moments as Apollo embraced her, he could feel her beating heart and the way the tree recoiled from him.

She had been Apollo’s first love and he vowed she would never be forgotten. The god was heartbroken, and now that his head had begun to clear from Eros’s spell he felt guilty for his relentless pursuit.

He plucked a sprig of the tree’s shiny, firm leaves and swore that the laurel would forever be his symbol and a plant that was more important to him than all others.

The Sacred Laurel

From the moment he saw her undergoing her transformation, Apollo vowed that the laurel would forever be sacred to him. He had never won Daphne’s love, but he would wear her token for eternity.

The laurel became a sacred symbol of Apollo. It was used often in the ancient world to denote the god’s power or favor.

It became a symbol of status that lasted beyond the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Even today, the image of the wreath of leaves is used in athletics and academia to signify success and achievement.

- A crown of laurels was given to the victors at the Pythian Games, the Penhellenic Games held in Apollo’s honor.

- The priestesses of Apollo’s temple at Delphi were said to chew laurel leaves to induce prophetic visions.

- When giving prophesy, the oracles sometimes shook laurel branches to symbolize Apollo’s role in inspiring them.

- A grove of laurels was kept inside the sanctuary of Delphi, Apollo’s holiest site.

- The temple of Apollo at Delphi contained a grove of sacred laurels.

- Those who had received oracles were crowned with laurel leaves as a sign of Apollo’s favor.

- In Rome, laurels became a symbol of victory.

- Emperors were often shown with laurel crowns and they were worn in triumphal marches.

- Apollo was almost always shown in art wearing a crown of laurel leaves. Along with his lyre, they became his most recognizable symbol.

While the Greeks called the plant daphne, the Latins gave us the world we use today. From “laurel” we get words of achievement and praise such as “baccalaureate” and phrases like “rest on your laurels.”

One of the most familiar uses of the word today is in the position of poet laureate. This honor began in Renaissance Italy, where writers who emulated the grand traditions of the Roman world were crowned in a fitting manner.

The Roman Emperors held the plant in such high regard as a symbol of favor and victory that they kept their own grove. It had supposedly been planted by Livia, the first empress, when a bird brought her a single sprig of leaves.

It was taken as an omen that the entire grove died just before Nero was assassinated.

The Greeks may have also been aware of the plant’s medicinal and astringent properties. Apollo was the god of medicine, so it was appropriate that his sacred plant had significant medical value.

In fact, Roman sources give even more medical use to the laurel. Pliny the Elder claimed the plant could cure spasms, paralysis, bruises, ear infections, headaches, and many more ailments.

In addition to how it could be used, the ancients also specified how it should not be used.

Because of its association with Apollo, the god of truthful prophecy, a form of divination developed in which people burned laurel leaves and interpreted the ways in which they cracked and burned. At least one Roman writer denounces this folk practice as a profane mimicry of Apollo’s sacred oracles.

Of course, in the modern world we have a much more practical use for laurel leaves. Most English speakers today know the plant by one of its common varieties, bay, and use the leaves in cooking rather than in ceremony.

Daphne as a Lesson in Pride

Ovid’s tale, while based on older Greek accounts, reflects a more Roman tendency to focus on emotion and characterization than the often more factual Greek writers.

This more descriptive style allows for deeper analysis of the legend. While many Greek writers wrote simple accounts of events, Ovid’s style was much more modern.

One of the overarching themes taken from the story of Daphne, like many such legends in Greek mythology, was the hazards of pride and boasting.

The story began because Apollo had insulted Eros. He bragged about his skill in killing the Python while demeaning Eros’s work as that of a “wanton boy.”

Apollo was not the only figure in Greek mythology to be undone by his own ego. Odysseus, for example, would have faced no further issues on his trip home if he hadn’t felt the need to mock the blinded cyclops as he sailed away.

Apollo’s pride directly resulted in the overwhelming lust and desire he experienced later in the story. The Greeks explained his single-mindedness through the magic of Eros, but his refusal to listen to Daphne’s dislike of him was another form of pride.

Apollo called after the nymph with a message that was as arrogant as his original statement to Eros. He could not believe that Daphne did not desire him; instead he assumed that the only possible reason for her to refuse him was because she didn’t know who he was.

In the end, Apollo was not the one directly punished for his pride. Daphne suffered the most.

Even though she was terrified and turned into a tree, Daphne kept her dignity and her virtue, however. As a follower in the ways of Artemis, this was something worth giving up her life for.

But Apollo was still hurt by his own behavior. He was heartbroken by the loss of Daphne.

The hurt and guilt he felt after Daphne was turned into a laurel tree was Apollo’s punishment for his earlier boastfulness and hubris.

While Apollo would have other lovers, he would never marry.

In fact, he had significantly few love affairs than the majority of his fellow Olympians. Some ancient writers took this as a sign that he had never loved any woman as much as he had loved Daphne, and he never really recovered from her death.

Apollo wore the laurel not only to remember Daphne’s beauty. He wore it as a symbol of penance for being the cause of her destruction.

Eros proved that his arrows were more than deadly. They could bring about suffering that would last for even the eternal lifetime of a god.

Metamorphosis in the Greek Myths

Daphne’s transformation into a tree was hardly unique in Greek mythology. The motif was used many times, particularly among nymphs seeking to escape the pursuits of lustful gods.

Syceus, for example, was transformed into a fig tree to escape Zeus. Pithys became a pine when she fled from Pan.

Ambrosia was transformed into a vine while running from a mortal man. Lotis was similarly changed when Priapus attempted to assault her.

These plants often became sacred symbols of the god that had, albeit indirectly, caused the nymph’s death.

Many other women, and some men, were changed into plants to save them from other types of suffering. They became vines, flowers and reeds.

Like many cultures, the Greeks used mythology to explain the world around them. The trees and flowers that were important to them had their own creation stories, often in the form of a nymph or human woman undergoing a transformation.

This explained the forms and beauty of the plants seen throughout Greece and the Mediterranean.

Clytie, for example, was turned into a sunflower to spare her the heartache of her unrequited love for Helios. That was why sunflowers followed the path of the sun as it moved through the sky.

The bending branches of the laurel tree were seen to be the arms of Daphne finally reaching to return Apollo’s embrace, whether because she finally accepted him or without free will was never clarified. The trees’ leaves never decay because Apollo vowed that they, like the nymph that they honored, would be eternally young and pure.

In all the different versions of Daphne’s story, there is only one in which she survives her encounter with Apollo. When she prays directly to Gaia for help, the mother goddess magically transports her to Crete and leaves a laurel bush in her place instead.

The Tragic Story of Daphne

The story of Daphne is one of the saddest in Greek mythology, but it is far from alone in that distinction.

Very often, the nymphs were portrayed as little more than playthings of the gods. They were beautiful and alluring, but many attempted to flee from the affections of males.

Many suffered tragic ends because of the gods. Several of Greek mythology’s saddest tales of lost life involve the nymphs.

These stories are often portrayed in both art and literature as romantic tales. Later Christians especially would find virtue in the nymphs that, like Daphne, sacrificed their lives to retain their virtuous chastity.

But the story of Daphne, particularly as it is told by Ovid, makes the terror and panic of the nymphs in these tales clear. Her wild flight from Apollo is told not in flowery verse, but in terms of hunting and death.

Daphne is portrayed like many other nymphs in art – as a beautiful and lithe maiden who gracefully transforms just as the god she’s fleeing from attempts to embrace her. But a closer look at the story shows the true tragedy of Daphne’s tale and so many others.