Aztec

Who Was Coatlicue in Aztec Mythology?

Who Was Coatlicue in Aztec Mythology?

Coatlicue was a mother goddess, but that does not mean that she seemed loving and nurturing. Keep reading to find out how the mother of many Aztec gods came to have a truly terrifying image!

Mother goddesses are often depicted as warm, protective, and nurturing. They have links to the earth, vegetation, or animals.

One of the mother goddesses of the Aztec pantheon, however, could not be farther from this image!

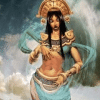

Coatlicue was a goddess that was very closely associated with snakes. She wore a skirt made of writhing rattlesnakes, had snakes instead of hands, and even had two serpentine heads instead of a human one.

She was also a prolific mother goddess, however. She had four hundred sons and one daughter before becoming pregnant a final time.

This last child, however, would prove to be the end of Coatlicue’s story. Murdered by her own daughter, Coatlicue would never get to see Huitzilopochtli.

So how did a mother goddess take on such horrifying imagery? Much of Coatlicue’s character, scholars say, might be based on symbolism.

Coatlicue: A Mother of the Gods

Coatlicue was a mother goddess in Aztec culture, but her appearance was hardly warm and nurturing.

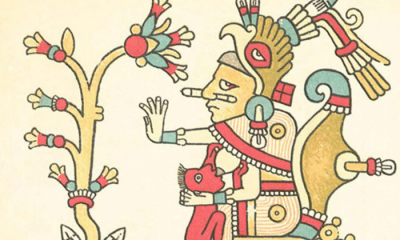

She was closely linked to snakes. She wears a skirt of writhing serpents, which in some images are depicted as rattlesnakes.

She is serpentine as well. She is often depicted with two serpent heads instead of a single human one, and in some images her hands are replaced with snakes as well.

Her other major attribute is no less gruesome. She wears a large necklace of alternating hands and human hearts.

Sometimes her hands are claws instead and her necklace includes skulls. In any combination, these images are unsettling.

The only indication of Coatlicue’s role as a mother is in the remaining human elements of her body. Her breasts and flattened and elongated as a result of having so many children.

While she did not look maternal, Coatlicue was a mother of multitudes. She had four hundred children who were collectively known as the Centzonhuitznahua, the gods of the southern stars.

She also had another son and a single daughter. These two would play an important role in her most well-known story.

According to legend, Coatlicue was the mother of the four hundred star gods and a single daughter, Coyolxauhqui. At that time she looked fully human.

One day, while she was sweeping a temple, a ball of feathers fell on her. She became pregnant, despite having no husband at the time.

When Coyolxauhui found out about her mother’s pregnancy, she was furious. She rallied her many brothers to attack their mother.

Coatlicue was decapitated. The instant she died, however, her son was born.

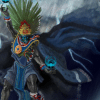

Huitzilopochtli came out of his mother’s body fully grown and dressed for battle. He was armed with a heavy serpentine club and, seeing his mother’s body, attacked his siblings.

Huitzilopochtli killed many of his brothers and drove the rest back to the places in the night sky. His sister Coyolxauhqui was beheaded in return for their mother’s death.

Her head was thrown into the sky, where it became the moon. Having avenged his mother, Huitzilopochtli became a god of war and the sun and the patron of the Mexicas, or Aztecs, of Tenochtitlan.

Some versions of the story claimed that Huitzilopochtli was able to save his mother by being born just before her death. These, however, seem to have been less popular than the story of her brutal muder at the hands of her angry daughter.

In most stories, Coatlicue was seen as a somewhat tragic figure. Killed by her treacherous children, she would never get to meet the son that avenged her.

A later myth, however, claimed that Coatlicue would eventually get to see her son.

Around the time of the Spanish arrival in Mexico, a legend was supposedly told in which Coatlicue seemed to predict the danger the civilization faced.

A group of magicians from the city of Tenochtitlan gathered together many gifts that they wanted to deliver to Coatlicue in Aztlan. Her tutor offered to guide them.

The magicians, however, struggled to carry their gifts up the mountain. Coatlicue’s tutor took the many packages from them and sprinted up the slope as though the weight meant nothing to him.

When the magicians arrived behind him, they found Coatlicue weeping because she never got to see her son. When she saw the magicians struggling to climb to Aztlan, however, she grew calmer.

She proclaimed that they had been unable to carry their gifts because their rich food and comfortable lives had made them too soft. Her son’s city would eventually fall, however, and when that happened she would be able to see him again.

My Modern Interpretation

The story of Coatlicue’s hope that she would see Huitzilopochtli again after Tenochtitlan fell seems to have been written when the danger was already known. Under the threat of Spanish invasion, the supposed prophesy more likely reflected events that were already unfolding.

Such prophecies were often added by Spanish conquistadores as well. The infamous legend that Cortes was the reincarnation of Quetzalcoatl, for example, seems to have been based more on misunderstanding of Aztec culture than actual belief of the time.

The story does, however, show a more sympathetic side to Coatlicue. Her sorrow over missing her son seems at odds with the monstrous form she presents.

Other aspects of Coatlicue’s story, however, are more open to interpretation by historians.

The story of Huitzilopochtli’s birth reflects the Aztec view of how each new day began.

While many cultures believed that the moon and sun followed one another across the sky in relative peace, the Aztecs viewed them as enemies. Each morning was a victory by the sun in his constant battle against the moon and stars.

Huitzilopochtli’s birth story represents the first of these fights. Although he was not yet a sun god when he was born, the story shows that he was destined to be the god that would fight the moon and the gods of the stars each day and prevail.

One theory suggests that Huitzilopochtli may not have always been the only deity in that story to be closely linked to the sun.

Coatlicue’s skirt of snakes is an intrinsic part of her character. It is so important that her name translates as “The Skirt of Snakes.”

Some historians believe that this skirt is important to understanding Coatlicue’s original role in the story. The snakes, they claim, may have represented flames.

In one story of the sun’s origins, several gods sacrifice themselves by immolation to give power to the new solar deity.

In a few versions of the story, some goddesses committed the same sacrifice. Coatlicue was named among them.

One theory is that the snake skirt represents one that is on fire. After the sacrifice, the skirts came back to life and were revered as divine in their own right.

While little evidence exists to suggest that the skirt itself was worshipped, images of Coatlicue do focus more on her skirt and snakes than on any human features. Even among the gods of the Aztec religion, she is noticeably inhuman.

Her skirt is not the only part of her body that is probably meant to be taken symbolically.

The two snakes she has in place of a head, some scholars believe, are not meant to be literal serpents.

Snakes are often used in Aztec art to visually represent a liquid. The two snakes coming from Coatlicue’s neck, some archaeologists say, represent the blood that came from her neck when she was beheaded.

A final cue to how Coatlicue may have been seen in the past is in the symbolism not of her art, but of her story.

Coatlicue was said to have had a child after being impregnated by a ball of feathers. Such miraculous circumstances give little justification for her daughter’s fury, though.

A popular theory is that the feathers Coatlicue came across in the temple actually represented something else.

In Aztec culture, some birds were said to be the spirits of dead warriors. A common interpretation of this story, therefore, is that Huitzilopochtli was not miraculously conceived but was the son of a fallen soldier.

In Summary

In Aztec mythology, Coatlicue was the mother of the war god Huitzilopochtli. He was born at the moment she was killed by her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, and four hundred older sons, the gods of the southern stars.

Huitzilopochtli killed his sister in return and threw her head into the sky to become the moon. Coatlicue went to Aztlan where, according to one legend, she mourned never seeing her sun under the cities of the Aztecs fell and he was returned to her.

Coatlicue’s imagery is among the most identifiable in Aztec art. A snake-headed goddess, she wears a skirt of coiling serpents and a necklace of human body parts.

Some scholars believe that much of this iconography includes snakes as symbols for other elements, however.

The two snakes coming from her neck are likely, based on artistic convention, representations of the blood that flowed from her when she was beheaded. Her skirt may represent flames, a reminder of an early version of the solar god legend in which she set herself on fire to give power to the sun.

Even the story of Huitzilopochtli’s miraculous birth may include hidden layers of symbolism. Because birds could represent the spirits of the dead, the tale of her impregnation by a ball of feathers could hint at an affair with a fallen soldier.

Thus, while Coatlicue may seem terrifying to behold, she is not as frightening a figure as she seems. While she looks monstrous, those images likely symbolize traditions in which violence was done to her rather than by her.