Chinese

Guanyin: The Goddess of Mercy

Guanyin: The Goddess of Mercy

A symbol of mercy, kindness, and love, Guanyin is one of Asia’s most recognizable religious figures. Keep reading to learn all about how Guanyin came to China and why she is so well-loved!

While Taoism has its roots in China, the country’s other major religious philosophy was imported. Buddhism originated in India but quickly spread into China and, from there, throughout East Asia.

As it spread, Buddhism’s characters and legends were adapted to local cultures. The connection to India was often preserved, but gods and sages took on the features and reflected the specific values of the cultures they entered.

In China, these figures were often syncretized with existing Taoist beliefs. Many stories arose that linked important people in Buddhist lore with the empire.

One of the most important figures to make this cultural journey was Guanyin, a Buddhist teacher based in Indian archetypes. She personified the values of kindness, mercy, and selflessness that Buddhists sought to emulate.

Guanyin quickly became the most important figure in Buddhism and an iconic part of East Asian religion. She is widely considered to be China’s most beloved deity.

The stories of Guanyin show why her appeal was so great that she is revered throughout Asia.

Guanyin’s Indian Origins

As a Buddhist deity, Guanyin originated with traditions from India.

In Mahayana Buddhism, the school that is most influential in China and East Asia, the term bodhisattva refers to a person who is on the path to being a buddha, or a fully enlightened person. They strive not only for their own enlightenment, but for that of all sentient beings.

Guanyin is the Chinese version of a well-known bodhisattva whose Sanskrit name was Avalokitasvara. This translates literally as “he who looks down upon sound.”

Avalokitasvara listened to the cries of those who needed his aid and endeavored to help every one. The Chinese name Guanshiyin, which was later shortened to Guanyin, retains this meaning by calling him “he who perceives the world’s lamentations.”

While some branches of Buddhism reject the notion of deification, Mahayana and others believed that some bodhisattva were divine and that other gods existed who reached enlightenment through their teachings.

In these traditions, Avalokitasvara is sometimes believed to have been the supreme creator god. Even when that was not the case, he was held in such high esteem that he was ranked higher than most, if not all, other deities.

According to the Lotus Sutra, Avalokitasvara could also take the form of any other god. Apparitions of Indra, Shiva, or another bodhisattva could all be an aspect of Avalokitasvara.

Avalokitasvara was known as the most beloved god in Buddhist cosmology. His adoption into Chinese culture, however, led to one major change in the way he was depicted.

Gendering the Deity

While Avalokitasvara was depicted as male, Guanyin is almost exclusively shown as a female.

Some of the earliest images of Guanyin in China were masculine, and that form continues to be seen occasionally today. It is rare, however.

The Lotus Sutra claimed that Avalokitasvara could take any form necessary to provide comfort to those in need. He could even change gender and become a woman if that helped the people who called upon him.

Because Guanyin is the personification of perfect kindness and empathy, female image became increasingly common by the 12th century. The bodhisattva came to be seen as a comforting, maternal figure.

This was especially important in Guanyin’s role as a patron of mothers and source of comfort during the pain of childbirth.

The bodhisattva had played this role in India, which had set the tone for how she would be depicted as a female. Similar imagery was used in China.

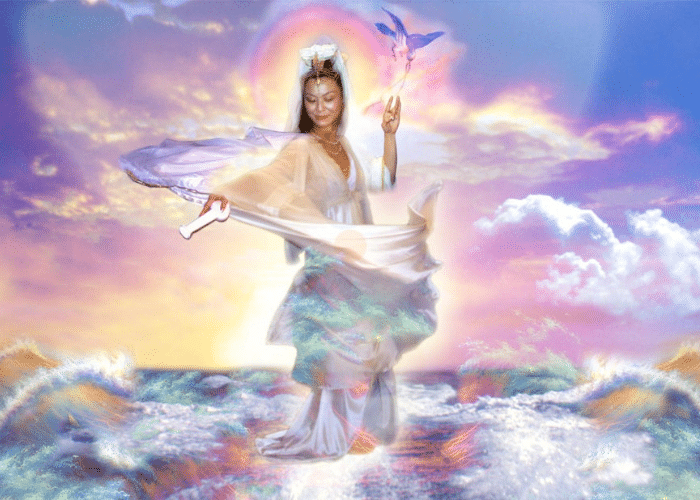

Guanyin is usually shown as a beautiful, graceful young woman dressed in pure white robes. She usually wears a necklace with emblems of royalty that can be either Indian or Chinese in style.

Like many Buddhist figures, she often wears an elaborate crown. Hers often depicts an image of Amitabha, the celestial buddha of light.

In her role as a patroness of mothers, Guanyin is sometimes shown holding an infant. In others, she often carries a jar of pure water and a willow branch, willow being used as a pain reliever in herbal medicine.

In art, Guanyin is also sometimes shown with a white cockatoo and two young children, her apprentices. At times, she is also flanked by two warriors, guardians that are a common motif in Chinese art.

Many parts of China also revere Guanyin as the patroness of fishermen and show her with a fish basket to hold a bountiful catch. She may also stand atop a dragon, showing her ability to keep people safe in the water.

Guanyin as the Princess

While much of Guanyin’s iconography and characterization originated in India, unique legends arose when she became popular in China. One of the most popular of these is the story of Miaoshan.

According to the story, Guanyin lived as a princess named Miaoshan. While her sisters and courtiers loved the lavish lifestyle of the court, from a young age Miaoshan was devoted to more spiritual pursuits.

Let me abandon the imperial palace, leave the family and venerate the Buddha, visit an enlightened teacher and follow the instructions of a good friend. I will walk in the right Way without any wavering. Leaving the earth-prison, escaping from this pit of fire, I want to become a buddha and ferry across the multitudes.”

The Precious Scroll of Fragrant [Incense] Mountain (trans. Idema)

Despite the princess’s wishes, and her mother’s prophetic dream that one of the royal children would become a buddha, Miaoshan’s father arranged for her to marry a man who was wealthy and uncaring, the opposite of the Buddhist ideals Guanyin studied.

She had little choice but to obey the commands of her father and king, however. Miaoshan agreed to marry the man as long as the marriage would ease three misfortunes. Otherwise, she would retire to a religious life.

Miaoshan asked that the marriage ease the suffering of people as they age, ease suffering caused by illness, and ease the suffering of death. When her father asked how these things could ever be accomplished, she replied that a doctor could help people with all three.

Furious that his daughter had named a doctor instead of the wealthy man he wished her to marry, the king punished her by restricting her food and water. Eventually, he allowed her to enter a temple to perform hard labor instead of taking vows as she wanted.

Even though the king ordered the monks to give her the hardest jobs, Miaoshin thrived in the temple. She befriended the animals that lived there and they helped her finish the arduous chores assigned to her.

Her father was so enraged when he learned of this that ordered the temple be burned to the ground. Maioshin put out the flames with her bare hands, however, and did not suffer a single burn.

Now afraid of his daughter as well as enraged, the king ordered Maioshan’s execution.

In one version of the story, she was immediately carried away to one of the torturous realms of the afterlife. She began to play music, however, and flowers bloomed around her to turn the worst hell into a new paradise.

In another version, the executioner tried to kill her with several different weapons, but each shattered before it touched her skin. Realizing that the king would have the executioner killed if he did not complete his task, she finally allowed him to strangle her.

Maioshin forgave the man and took on his karmic guilt so he would bear no blame for her death. In doing so, she was sent to one of the hellish realms.

When she saw the suffering there, she was so moved that she released all her good karma to free them and transform the land. Yama sent her back to the earth as the ruler of Fragrant Mountain to prevent his entire Underworld from being destroyed.

There, Maioshin cured many people, including her father, from terrible diseases. Seeing all the suffering that morals endured, she vowed to never leave the earth until all suffering had been eliminated.

While some people believed that the story of Maioshin was Guanyin’s origin, most today think that the princess was a reincarnation of Guanyin. Maioshin was one of many forms the goddess took to help the people of earth.

Names Throughout East Asia

From China, Buddhism spread throughout East Asia. With it spread the veneration of Guanyin.

Each culture that adopted the religion and its most beloved figure had their own interpretation of Guanyin. Her names throughout Asia include:

- Her name is Gwun Yam in Cantonese, Kwun Yam in Hong Kong, and Kun Iam in Macau.

- In Japan she is called Kannon. The Canon camera company was originally named after her as a goddess of light.

- The people of Thailand call her Phra Mae Kuan Im, or Goddess Kuan Im.

- A similar title is used in the Khmer language. Her full title, Preah Mae Kun Si Im is always used. Preah Mae means “Goddess Mother.”

- She is known as Gwan-eum or Gwanse-eum in Korean.

- The name Quan Am is used in Vietnam.

- Kwan Yim Medaw is her name in Burma. Meadow means “Mother.”

- Indonesians call her Kwan Im. The title Mak, “Mother,” is sometimes added.

- In Tibet, where a distinct form of Buddhism is practiced, she is known as Chenrezik.

The fact that these people, and more, recognize Guanyin shows her popularity in Buddhist culture. Despite local differences in religious practice, the same figure holds a foremost place in all their belief systems.

Many of these languages also highlight one of Guanyin’s most important features. They call her “Mother,” noting that she is a caring, merciful, and nurturing goddess.

The Disciples of Guanyin

In China, Guanyin is believed to have done more than directly care for those in need. She also trained disciples who would both spread Buddhist doctrine and continue her good works.

Her most famous student was Shancai, who is sometimes shown as one of the two children at her side. His story was first told in India, and Chinese tradition continued to say that he had been born there.

Born with a severe disability, Shancai nevertheless traveled to meet Guanyin as she was teaching. After having a discussion with him, the bodhisattva decided to test his resolve to see if he was serious about learning from her.

She conjured an illusion of three pirates chasing after her. Shancai crawled after them in an effort to save the teacher, even throwing himself off a cliff after them.

Guanyin caught him as he fell. She healed his disability and he became her most devoted student.

Many years later, the son of a Dragon King was caught in a net while swimming in the form of a fish in the South China Sea. Unable to transform or get help from his father when the fishermen took him onto dry land, he called out to the heavens for help.

Guanyin sent Shancai to purchase the Dragon King’s son at the fish market, but Shancai discovered that an intense bidding war had started. Seeing that the fish was still alive several hours after being caught, people speculated that eating it would grant immortality.

Shancai pleaded with the fishmonger to spare the fish, angering the crowd. Then Guanyin projected her voice and decreed to the mob that a life should belong to the person who would save it, not to those who would destroy it.

Shamed by their behavior, the crowd dispersed and the Dragon King’s son was returned to the sea. Guanyin came to be revered on the coast both for protecting the fish and for sparing future fishermen the dragon’s wrath.

In thanks, the Dragon King sent his granddaughter, Longnu, to give Guanyin the Pearl of Light, his most precious jewel. Longnu was so overwhelmed by Guanyin that she immediately asked to be taken on as a disciple.

Guanyin was even said to have attracted an animal as a fervent student of Buddhism.

During the Tang dynasty, a small parrot left its nest to find food for its sick mother. While it searched the forest for her favorite food, it was captured by poachers.

The parrot managed to escape, but by the time it found its way home its mother had already died. The parrot grieved and held a funeral for its mother, then left the forest to seek out Guanyin and learn from her.

The parrot became a symbol of filial piety. Even when studying the teachings of Buddhism, it set the example that proper respect must be paid to parents and elders first.

Beyond Buddhist Doctrine

Guanyin was one of the most well-known and important figures in Chinese Buddhism, but her influence was not limited to people of that faith.

One of the hallmarks of religion in Chinese culture is the way in which many different traditions become syncretized. The religious and philosophical traditions of China often adopt from one another, trading gods and legends to create a folklore that does not belong to any one group.

It is not unusual, therefore, that Guanyin became a prominent figure in Taoism as well as Buddhism. Taoist tradition claims that she was a Chinese woman who became an immortal through her good works.

Similarities between Guanyin and some other Taoist figures led to her being viewed in a unique way. Shared iconography with Hariti increased her association with childbirth and made her a fertility figure, while her role as a patron of fishermen led some to say that the goddess Mazu was an incarnation of Guanyin.

Taoists also see her as an agricultural goddess. According to legend, after the Great Floor she was so concerned about the survivors that she sent a dog to them with grains of rice in its tail so they could reestablish their farms.

Her cult has continued to evolve in Chinese folk religion. In the 20th century, some people began to claim that Guanyin was a protector of air travelers, likely inspired by her patronage of travel by sea.

Several new religious movements in Asia have incorporated Guanyin into their modern beliefs. In the Zaili sect in Northern China she is the main deity worshipped, while one group in Japan views her as an ideal bridge between different Buddhist traditions.

Images of Guanyin also had an influence on a major religion that entered China later in its history.

When the first Jesuit missionaries began to work in China, they took note of Guanyin. They coined the term “Goddess of Mercy” when describing China’s existing religious beliefs to others.

They also saw close parallels to their own faith in the images of this goddess. Artwork featuring a lovely, kind woman holding a child was quite familiar to them.

As it had done earlier in Europe, the Christian faith used this commonality as a tool in making their religion appealing to East Asia. Throughout the region, missionaries preached that the Virgin Mary was their version of the beloved goddess Guanyin.

This even allowed Christians to thrive under dangerous conditions.

Looking to limit outside cultural influence, Japanese rulers in the Edo period made Christianity illegal on punishment of death. Christians used images of Kannon, the local version of Guanyin, with an infant as a stand-in for the Virgin and Child to hide their true faith.

Guanyin’s Universal Appeal

Guanyin is the name given in China to one of Buddhism’s most important figures. A bodhisattva, or person on the path to enlightenment, in many regions she takes on the qualities of a goddess.

Guanyin originated as a character in Indian Buddhism called Avalokitasvara. A champion of mercy, he was well-loved for ending suffering wherever he found it.

While Avalokitasvara was typically shown as male, he had the ability to take on any form needed to ease a person’s suffering. Images of Avalokitasvara an a female form because popular to show him personifying the caring nature of a mother.

In China, this female figure was called Guanyin, a direct translation of Avalokitasvara’s Sanskrit name. Most often shown as female, She soon became one of the area’s most well-loved figures.

Many local traditions grew up that expanded Guanyin’s role in Chinese culture. She became the patroness of childbirth, fishermen, and was thought to have a special concern for the sick and disabled.

Stories of Guanyin’s incarnations in China and her students there became popular and influenced her local iconography. Devotion to her as either a religious leader or a goddess spread throughout Asia.

Guanyin also became syncretized into many other regional faiths. Chinese Taoists see her as an immortal of mercy and patron of mothers while Asian Christians have long used her imagery in representations of the Virgin and Child.

Guanyin became one of Buddhism’s most iconic and well-loved figures because of her universal appeal. A loving, kind figure who represented mercy and charity, she embodied Buddhist doctrine as a familiar maternal figure.