Egyptian

Isis: The Queen of the Egyptian Gods

Isis: The Queen of the Egyptian Gods

Isis is arguably the most well-known goddess of ancient Egypt, but how well do you realy know her story? Keep reading to learn more about the wife and mother of Egypt’s godly kings!

Today as well as in the past, Isis is considered the most popular and powerful goddess of the ancient Egyptian pantheon.

The wife of Osiris, her role went far beyond that of royal consorts in many other traditions. She was seen as powerful and strong-willed in her own right even though many of her stories emphasized her role as a wife and mother.

The Egyptians viewed her as one of their greatest protectors and the archetype for all queens. She was a loving, nurturing mother who could also be fiercely, even violently, protective.

In her own culture she was view as a royal mother, patroness of kings, mistress of magic, source of healing, and the inventor of mourning. Her appeal ultimately spread far beyond this culture, however.

Isis and Osiris

The worship of Isis was closely linked to that of her husband and brother, Osiris. Evidence for both of them is rarely seen before the Fifth Dynasty in the middle of the second millennium BC.

While initially centered around the city of Heliopolis, their importance grew significantly over time. Eventually, they and the Ennead, the principal gods of that city, became nationally important.

According to the mythology of Heliopolis, Isis and Osiris were two of the four children of the earth god Geb and his partner, the sky goddess Nut. Their siblings were Set and Nephthys.

Isis and Osiris were married. Although some legends claim that Set and Nephthys were as well, there is much less evidence for that union.

Osiris was given the throne and made the king of all of Egypt. He was a wise and just ruler who brought stability to the land.

The king was in almost constant conflict with his brother, however. Set represented the forces of disorder and chaos, so he and his brother were often at odds.

There were many legends that explained why Set felt such animosity toward Osiris, although their conflict was often intentionally left out of written sources in Egypt to avoid invoking a taboo. While many modern retellings of the story simply say that Set was jealous of his brother’s position, others go into more detail.

In one account, Osiris had an affair with Nephthys. In another, he kicked Set during a minor dispute.

Whatever the offense, it was great enough that Set vowed to get revenge. He decided to kill his brother and take the throne for himself.

The Birth of Horus

The Egyptians did not write about the death of Osiris in detail. A full description would have been seen as an unlucky invocation of tragedy.

What is known is that the story of what happened immediately following the king’s death evolved to become more complex and dramatic.

According to later stories, Set was not content simply to kill his brother. He further desecrated the corpse by cutting it into sixteen pieces and scattering them across Egypt.

Some historians believe that this story developed as a way for more local cult centers to have a connection to the god. Several temples throughout Egypt claimed to have been built on the site where one of Osiris’s body parts was thrown.

In Egyptian belief, however, a soul could not move on to the afterlife, Duat, unless the body was whole. Knowing that Osiris would be trapped as a spirit if his body was not treated with proper respect, Isis set out to find the pieces.

With the help of her sister Nephthys, Isis searched all of Egypt for the pieces of her husband’s body. They wailed in mourning as they searched.

Eventually, the body of Osiris was put back together. According to a later tradition, the only part that was never found was his phallus, which had been thrown into the Nile and eaten by a crab.

Isis took the body to Anubis, who worked with Thoth to carefully piece it together and preserve it. They did such a good job that Osirus looked almost entirely untouched by death and became the first mummy.

Isis had an ulterior motive for preserving her husband’s body, however.

Although she had adopted Anubis, who according to some was the child of Nephthys and either Set or Osiris, Isis and Osiris never had a child of their own. This meant that the deceased king had no heir, so his brother was free to claim the throne.

Isis was able to use her magic to breathe life back into her husband’s body for a brief period of time. She conceived a son in the moments that Osiris was alive again.

Isis the Healing Goddess

Thoth warned Isis, however, that Set would try to destroy her son the moment he learned of the child’s existence. The queen had to go into hiding to ensure that her baby was not killed as his father had been.

Several stories emerged in later years that detailed the time Isis spent in hiding. This period of time was a popular setting in folk stories even though it played little role in more organized belief.

One legend said that Isis went to Atum, the progenitor of the gods, for protection. Atum granted it and sent a serpent, Werethekau, to protect her.

Another version of the story said that Set attempted to hold Isis prisoner, but Nephthys helped her escape. She fled the palace with seven scorpions, guardians sent by the goddess Serqet.

According to the Greek writer Herodotus, a story was told about the birth of Horus that was similar to that of Apollo and Artemis in his own culture. Because this was recounted very late in Egyptian history, in the 5th century BC, it was almost certainly influenced by contact with Greece.

In this story, Isis sought out the goddess Wadjet on the island of Pe. She cut the island free from its moorings so that it floated away, making it harder for Set to reach her.

The birth was long and difficult until Isis received aid from a pair of gods who anointed her with blood. Her son, Horus, was born on the first day of spring.

Most legends claimed that Isis and her son hid in the marshy lands of the Nile Delta. Other gods, including Hathor and Nephthys, brought them food and warned them when Set’s followers approached looking for them.

Another popular tradition claimed that Isis sometimes disguised both herself and her son as humans so she could blend in with the population of the area. They moved mostly undetected.

These stories were often featured in spell books that used such legends to instruct the reader. One such text contained magical charms to use in healing.

In one story, for example, the scorpions who guarded Isis took vengeance when a wealthy woman rudely turned the disguised goddess away. The strongest scorpion went into the woman’s home and stung her young child.

The woman screamed for help, but the people around her ignored her. Only Isis, who realized what her guards had done, rushed to give aid.

The text included the methods Isis used in healing so that human readers could employ the same techniques. Some of these cures were practical, but others were more purely magical.

The cure for a scorpion sting was among the magical remedies. Isis spoke the true name of each scorpion and demanded that the poison leave the child’s body.

She used a similar tactic in another story to heal a god.

Knowing that her son would need greater power as he grew, Isis used a similar incantation to give him power over the sun god Ra.

Ra was elderly, but was still powerful and intelligent. To have power over him, Isis needed his true name which she knew he would not give easily.

She collected a bit of the god’s spittle, supposedly because he was old enough that he had begun to drool, and worked it into some clay. She fashioned a cobra and used her magic to bring it to life.

Knowing where Ra took his daily walks, Isis waited for him and put the cobra down in his path. When it bit him, she offered her healing powers.

To heal him, however, she needed his true name. The magical cobra’s venom had been made from Ra’s own fluids, so she had to use his name to command it out.

Ra resisted giving her his name for as long as he could, but eventually relented. Isis learned the sun god’s name, which she could later give to her son to give him more power.

Break out, scorpions! Leave Re! Eye of Horus, leave the god! Flame of the mouth – I am the one who made you, I am The one who sent you – come to the earth, powerful poison! See, the great god has given his name away. Re shall live, Once the poison has died!

-Papyrus Turin (trans. Shaw)

Eventually, Isis’s quest to give her son power would result in her having to heal herself.

Horus returned when he was grown to challenge Set for the throne. The gods were unable to agree as to which one had the better claim, so a long battle began to establish supremacy.

Set and Horus fought bitterly. In addition to physical combat, they also competed in feats of strength, endurance, and magic to prove which should be the king of the gods.

In one such contest, the two gods transformed into hippopotami to see which could stay submerged in the Nile longest. Isis, however, was not confident that her son would prevail.

She made a harpoon out of bronze and threw it into the water where she believed Set was submerged. It hit her son instead, and Horus emerged from the river in a rage.

Blinded by his fury, Horus cut off his mother’s head with a single blow. Her magic was so powerful, however, that she survived.

Isis replaced her head with that of a cow that was grazing nearby until she could be fully healed. This unusual story explained why she was sometimes shown with the head of a cow in cult images.

The Iconography of the Goddess

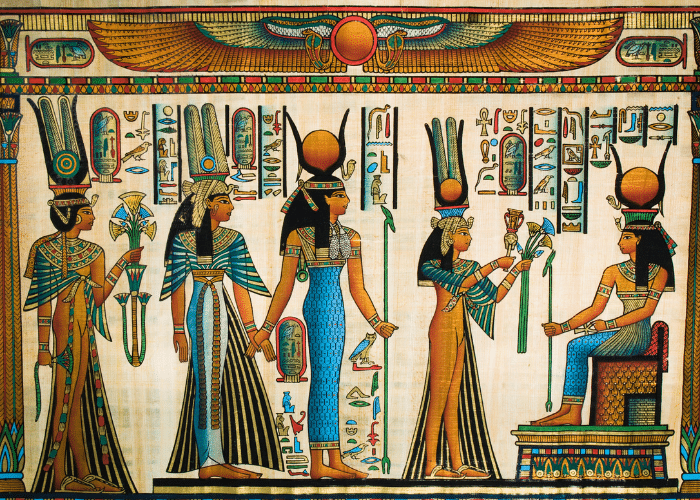

Although Isis was occasionally shown with a bovine head, this was not the most typical way she was depicted in Egyptian art.

While many of the individual myths changed over time, Egyptian artwork remained relatively static for millennia. The way in which the gods were shown had some regional variations, but was remarkably uniform over large periods of time.

This means that Isis and the other Egyptian gods had very immediately recognizable iconography that could be seen in many of their images. For Isis, these included:

- The sistrum: An ancient percussion instrument, this was often played during ceremonies. It referenced her position as a mourner who would have played such an instrument at her husband’s funeral.

- Kite: Both Isis and Nephthys were sometimes shown with kites. The birds’ search for carrion parallel their search for the body of Osiris, and the cries of a kite were said to resemble those of mourning women. In some legends, she even took the form of a kite during the conception of Horus.

- The solar disk: Although the cow horns and solar disk were more commonly associated with Hathor, they were occasionally brought into the iconography of Isis. They reflected her position as the mother of a solar god.

- The ankh: Like many deities, particularly those associated with royalty, Isis often carried a symbol of life.

- A crown: In later eras, Isis often wore a headdress showing a cobra and a vulture. This was a symbol of royalty, reflecting her position as both the wife and the mother of kings.

- The tyet: This symbol was similar to the ankh, but symbolized death instead of life. It was often included in burials as a protective charm for the dead.

- A tree: Isis occasionally took the form of a tree or emerged from one, offering food, in her images. This referenced her role as a nourishing mother figure.

- Snake: In a few later images, Isis is shown with the body of a snake. This unusual form came through her combining with another goddess, Renenutet, as a patroness of agriculture.

Isis was generally shown as a beautiful queen, wearing a sheath dress and emblems of royalty. Although her imagery occasionally included animal elements, she is one of the few Egyptian deities to be shown most often in an entirely human form.

In sculpture, Isis was often shown in position that reflected her stories.

One popular image was of the goddess holding her young son in her lap. This emphasized her role as a protective mother goddess.

Other pieces of art showed Isis and Nephthys in mourning for Osiris. In the elaborate funeral rituals of ancient Egypt, their cries during the search for his body were seen as the prototype for later acts of mourning.

Isis and the Kings

As part of the story of Osiris and Horus, Isis was also closely linked to the power of the Pharoahs in ancient Egypt.

Because of her restoration of Osiris and protection of Horus, Isis was portrayed as a defender of royal power. Living Pharoahs claimed to be incarnations of Horus and Osirus, so Isis served as a mother to them.

Images of Isis with her child often showed the king instead of a young Horus. Even in adulthood, Pharaohs were sometimes depicted sitting on the goddess’s lap or even nursing from her.

These images symbolized the role of Isis in conferring kingship to the Pharoah. Just as she nurtured her own son until he came to power, she did the same for living kings.

This defense of the throne even took on a militant aspect. Although she was a loving, maternal goddess, when fighting on behalf of the Pharoah she was described as a fierce protectress of the nation who was as effective as a million trained soldiers.

As the wife of Osiris, Isis also served as a symbol of the queens of Egypt.

The wives of the Pharaohs were often expected to be companions and advisors to their husbands and sons. Isis provided the template for the ideal Egyptian queen.

When shown in royal regalia, Isis emphasized the importance of such queens in the political structure of Egypt. While they did not hold any direct power, they supported their husbands and raised future kings who they would protect and promote at any cost.

This support of kingship extended beyond death.

Although she had no death narrative of her own, Isis was sometimes shown alongside the gods of the Underworld. In Duat, she assisted kings on their journey and was one of the deities who battled the serpent of chaos, Apep.

Most gods associated with the Underworld had a legend that placed them there. For Isis, however, her role as the wife of the king meant that she continued to support him even after his death in whatever way needed.

Beyond Egypt

Althogh her cult developed later than many others in Egypt, Isis became the country’s foremost goddess. She found such popularity that she became the most enduring goddess of the pantheon.

When the Greeks and Romans visited Egypt, they found the gods there exotic and bizarre. Although many were likened to more familiar Greco-Roman deities, their forms and legends struck many ancient writers and entirely foreign.

Isis, however, appealed much more to people in these European cultures. She became on of the few Egyptian deities to develop a strong cult outside of the Nile Valley.

Although she was mostly portrayed as human, the Greeks played up her exotic origins. While she later took a more Hellenized form, many Greeks were drawn by the ancient, mysterious origins of the Egyptian mother goddess.

Her cult in Europe depicted her as the inventor of marriage and motherhood. She was the archetype of a loyal, protective, and nurturing female figure.

Her role as a protector and mother was emphasized by her Egyptian origins.

Durng the Roman Empire, much of the city’s grain was imported from Egypt. Isis became a representative goddess of the Nile Valley’s fertility and the nourishment it gave to the entire Empire.

People also knew that Rome’s stability hinged on these regular shipments of grain. As the Egyptian mother goddess, Isis protected the entire Empire, particularly the capital city, from chaos.

Isis also tok on roles as a cosmic goddess because of her familiar links to the sun. Some believers credited her with influencing the movement and cycles of not only the sun, but the moon and stars as well.

Because the Greeks and Roman often equated forgeign gods with their own, it was easy to give Isis links to their own mythology. Horus, for example, was often compared to Apollo, so Isis was sometimes called the mother of the Greco-Roman god by her followers.

Her foreign origins were never entirely forgotten, however. Despite the Hellenized form her worship and imagery took, Isis was never fully embraced by everyone in Europe.

In Rome, shrines were established to Isis on the Capitoline Hill alongside those of the Roman gods. These were destroyed in the 1st century BC, however, because they were seen as being at odds with the state religion and cultural identity of Rome.

Although her cult was temporarily banned during the wars between Octavian and Cleopatra, Isis never entirely disappeared from Roman life. A hundred years later, the Flavian emperors even named Isis, along with traditional Roman deities, as one of the patrons of their reigns.

Even as Egypt itself was conquered by Rome and began to decline, the cult of Isis spread throughout the Empire. Roman followers took their belief in Isis as far as Londinium (London), Spain, and Syria.

After the fall of Rome, Isis was more widely-remembered than most other gods of the Egyptian pantheon because she had been so widely-worshipped in Europe. Later European writers, seeing the same exotic wisdom in her Egyptian origins as the Greeks and Romans had, continued to reference her.

European audience in later eras also saw a familiar figure in the iconography of Isis. Images of the goddess holding her young son may have influenced depictions of the Virgin Mary and Christ, keeping her more relevant than many of the more exotic gods of the ancient world.

Therefore, while many other Egyptian deities were largely forgotten until the advent of modern archaeology, Isis remained in the popular imagination.

This continues in the modern era, as Isis is one of the most popular goddesses in some neopagan movements. As a deity that encompasses both the protective and nourishing aspects of a royal mother goddess, Isis is seen by some modern worshippers as a powerful depiction of feminine power.

The Goddess Isis

In Egyptian mythology, Isis was the wife and sister of Osiris. She served as the prototype for the loyal, helpful queen.

After Osiris was murdered by their brother, Set, Isis reassembled his body. She conceived an heir, Horus, who she protected until he was old enough to challenge his uncle.

Folk stories of Isis as a protective mother were popular in later Egyptian culture. These often included references to her healing powers and magical abilities and emphasized her ferocity in keeping her son safe.

Egyptian Pharoahs believed that, as incarnations of Horus, Isis nurtured and protected them in the same way. She also illustrated the proper role of queens, from being promotors of their young sons to the mourners at their husbands’ funerals.

Isis was one of the Egyptian deities who gained a large cult following outside of the Nile Valley, first in Greece and then throughout the Roman Empire. Although her foreign origins were never forgotten, European worshippers saw her as a powerful protectress of their own lands, as well.

The widespread appeal of Isis and spread of her cult through Rome made her more recognizable than most other Egyptian gods and goddesses even after the decline of her cult.