Irish

Who Was The Dagda in Irish Mythology?

Who Was The Dagda in Irish Mythology?

The Dagda appears often in Irish legends, but just who was this king and father of the gods? Keep reading to learn more!

The Dagda is one of the most prominent figures in the early myths of Ireland. The brother of the first king of the Tuatha de Dannan, he was one of the first of those people to come to Ireland.

He plays a prominent role in the story of how the Tuatha de Dannan gained control of Ireland and became its gods. His importance goes far beyond those early battles, however.

The Dagda is often thought of as an earth god who had dominion over agriculture and fertility. While he was often associated with food, however, this was not his only function.

The Dagda was a master of magic and of warfare. Known for his wisdom and strength, he was a formidable opponent both on and off the battlefield.

He became one of Ireland’s legendary kings and was the father of many of the gods. He was the husband and compliment to one of the pantheon’s most famous goddesses as well.

The Dagda was a powerful figure whose magic bridged the divide between life and death. A god of the earth, he was also a god of death, order, and natural law.

The Dagda as an Earth God

The Dagda, An Dagda in Irish, is usually interpreted as a god of the earth.

He is often compared to the Norse god Odin because of his association with magic. The two gods were likely derived from the same source.

Both were also father figures in their respective pantheons. The Dagda’s position as a father to many other gods and heroes emphasized his role as a god of fertility and bounty.

Many myths emphasize food and plenty when they discuss the Dagda. He was said to not only have an immense appetite, but also to be able to provide amply for others.

The Dagda owned a cauldron that never went dry, so no matter how many people he hosted no one would ever be left unsatisfied. His ladle was big enough for two men to fit into.

He also owned an orchard where the trees were always heavy with ripe fruit. He had two pigs so that one could always be roasting while the other grew to replace it.

The first mention of the Dagda in the telling of the Second Battle of Mag Tuired also concerns food.

While Bres and the Fomorians ruled over the Tuatha De Dannan, the Dagda worked hard every day. Each night he came home and ate a rich meal.

A blind man named Cridenbel was jealous of the Dagda’s feasts. His mouth grew in his torso and his appetite was almost as large as the Dagda’s own.

Cridenbel told the Dagda that honor demanded the bounty be shared, so Cridenbel should be given the three best morsels of the Dagda’s meal. Each bite he took, however, was the size of an entire pig.

These three bites amounted to a third of the Dagda’s meal each day. The god soon grew to resent his neighbor for taking advantage of his hospitality and became noticeably thinner from having so much food taken from his plate.

Mag Oc saw the Dagda’s troubles and helped him devise a way to end Cridenbel’s theft. He gave the Dagda three gold coins to put in his food.

When Cridenbel asked for the three best morsels from the Dagda’s meal, the three coins were more valuable than any of the food. Cridenbel ate the coins and died when the gold stuck in his stomach.

The Dagda was accused of poisoning his neighbor and violating laws of hospitality, offenses that were punishable by death. He escaped this fate, however, by cutting open Cridenbel’s stomach and proving that it was gold, not poison, that had killed him.

This story shows that, as a god of abundance, the Dagda was likely involved in matters of hospitality and generosity. While he encouraged sharing food with his bottomless cauldron, he could also punish those who abused the traditions of hospitality to the detriment of others.

Descriptions of the God

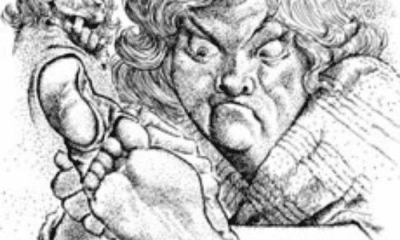

While the Dagda’s name meant “The Good God,” many descriptions of him do not seem to portray him in that way.

He is often shown as a somewhat buffoonish and comical character. He is large and gruff with a thick beard and unruly hair.

Descriptions often note that his clothes are far too small to fit his enormous frame. His stomach and buttocks stick out, emphasizing his oafish portrayal.

Despite this, however, the other characters in these legends do not seem to treat the Dagda with the disdain that would usually be seen for someone who appeared so foolish.

The Tuatha de Dannan deferred to the Dagda as a wise leader, a fearsome fighter, and a skilled mage. He was a chief among the druids and held in high regard.

Some stories even contradict the god’s brutish appearance in the way the other characters talk about the Dagda. He is described as beautiful and powerful even in some texts where his clothes are too small and his hair is unkempt.

Many historians believe that the Dagda’s oafish appearance was not an original feature of Irish mythology.

When later Christian writers recorded the legends of pagan Ireland, they had a vested interest in making the gods seem less noble and divine. In comparison to their own god, they wanted to make the pagan gods seem less legitimate and attractive.

In some cases, gods were demonized or made into less powerful faeries or other folklore characters. In the case of the Dagda, he was made to seem foolish and brutish.

Some contemporary sources challenged this portrayal. One text claimed that the Dagda was seen as a beautiful god whose magic made him a father of the earth.

The Dagda in Battle

Despite being associated with bounty and fertility, the Dagda was also seen as a powerful warrior.

Most Irish gods and many of the goddesses took part in the battles that formed part of their legends. This was especially true of the Tuatha de Dannan who first came to Ireland and had to fight two battles for supremacy over the island.

While the Tuatha de Dannan easily defeated the Fir Bolg, they were soon overpowered by the Fomorians. Their king, Bres, had a Fomorian father whose people he favored more than his mother’s Tuatha de Dannan kin.

In the years that the Fomorians controlled Ireland, the Dagda was one of the key figures in planning how to fight back. His brother, Nuada, had once been king so they spent years in council preparing their rebellion.

According to the Cath Maige Tuired, which tells the story of the Tuatha de Dannan’s war against the Fomorians, the Dagda earned his title as the Good God by vowing to wield the greatest powers his people could muster against their enemies.

Figol mac Mamois, their druid, said, “Three showers of fire will be rained upon the faces of the Fomorian host, and I will take out of them two-thirds of their courage and their skill at arms and their strength, and I will bind their urine in their own bodies and in the bodies of their horses. Every breath that the men of Ireland will exhale will increase their courage and skill at arms and strength. Even if they remain in battle for seven years, they will not be weary at all.

The Dagda said, “The power which you boast, I will wield it all myself.”

“You are the Dagda [‘the Good God’]!” said everyone, and “Dagda” stuck to him from that time on.

-Cath Maige Tuired, The Second Battle of Mag Tuired (trans Gray)

In addition to raining down fire and turning the Fomorian’s own bodies against them, the Tuatha de Dannan used their magic to make the land work in their favor as well. Their magicians said that the mountains would shake and the lakes and rivers would refuse to give water to the Fomorian soldiers.

By taking on all these powers, the Dagda became a god of the earth rather than just of agriculture. In addition to the fertility and bounty of nature, he also represented its power.

Before the battle, the Dagda also made an alliance with the goddess of war.

The Morrigan is sometimes named as the Dagda’s wife, but many scholars interpret their union in the Cath Maige Tuired as a more symbolic one. It mirror ceremonies in which a goddess would ritually wed a new king to legitimize his claim to power.

After this meeting, the Morrigan gave the Tuatha de Dannan a powerful boon. She killed Indech mac De Domnann, the king of the Fomorians, and took his blood for the mages to use against his people.

The battle went as the Morrigan had prophecized: The Tuatha de Dannan won, but they paid a heavy price.

Both of the Dagda’s brothers were killed and he was mortally wounded. It took many years for his wound to prove fatal, however, so directly after the battle he went on another adventure with Lugh and Ogma.

After the battle, many of the Fomorians ran to escape the fury of the Tuatha de Dannan. Some of these stole the Dagda’s harp, one of his prized magical possessions.

He and Lugh gave chase to these thieves and eventually found them, led by Bres and his father, feasting in their hall. He summoned his harp, which killed nine Fomorians as it flew across the room.

The Fomorians would have killed them, but the Dagda quickly put the harp’s magic to work. He played sorrowful music so they were paralyzed by emotion and joyful music so they laughed too hard to attack.

Finally, he played a song that lulled all the Fomorians in the hall to sleep. Thus, the three Tuatha de Dannan were able to escape without harm.

As they returned, the Dagda also rounded up all the cattle the Fomorians had taken from them as tribute during the years of oppression. He returned them to his people, and is thus credited with bringing prosperity back to Ireland.

The Good God’s Attributes

The Dagda’s harp was only one of many magical items he used. His relics were considered to be some of the most powerful and important in Irish mythology and are sometimes mentioned in later stories, after his death.

The Dagda’s possessions showed the full range of his powers. Feuled by strong magic, they represetned both his might and that of the Tuatha de Dannan. They were:

- The coire ansic: His bottomless cauldrom was one of the four greatest treasures of the Tuatha de Dannan. It represented his power as a fertility and earth-based god because it ensured that his people would never go hungry.

- Uaithne: The Dagda’s harp did more than play music that manipulated men’s emotions. Its song also ensured that the seasons aligned in their correct order, meaning that the Dagda could commandnoth men and nature to follow the correct course.

- The lorg mor or lorg anfaid: Interpreted as either a staff or a club, this magical weapon showed that, life many fertillity deities, the Dagda bridged the divide between life and death. A touch from one side brought death, but the other side had the power to bring people back to life.

The Dagda’s attributes helped to emphasize the fact that he was a god of both life and death.

These concepts were often linked to one another in ancient religions. Not only were they complimentary opposites, but new life also grew from the decay that followed after death.

The Dagda ensred life by feeding his people and could restore it with his staff. That same staff could bring death, however.

With his harp, Dagda ensured that these ideas followed in their natural order. The cycle of life and death was one of the many aspects of nature that was kept in order by the Dagda’s magical music.

The Family of the Dagda

The Dagda’s family also emphasized the duality of life and death.

Although he had many mistresses, including the river goddess Boann and the Fomorian king’s daughter, he was usually said to be married to the Morrigan.

The Morrigan was a goddess, or trio of goddesses depending on the source and its interpretation, of war, death, and fate. She was sometimes seen as an alluring figure, but just as often appeared in the guise of an old crone.

The pairing of the Morrigan and the Dagda represented a common marriage in mythology. Like Hades and Persephone, their marriage united the ideas of fertility and death.

One of his sons was Bodb Derg, whose mother may have been the Morrigan. Like one of her alternative names, Badb, his name includes the word for “crow.”

In The Children of Lir, Bobd Derg is elected king of the Tuatha de Dannan after his father’s death. He was the last of these kings to rule Ireland, as the Tuatha de Dannan were pushed in to the underground sidhe shortly after his rule began.

Bodb Derg may not have been the child of the Morrigan, however. One account claimed that she and the Dagda had only one child, who was killed by Dian Crecht in infancy for his monstrous appearance.

Not all of the Dagda’s children were monstrous, however. His most well-known daughters are remembered, in part, for their beauty.

Brigid and Aine were the goddesses of spring and summer. While Aine’s parentage sometimes varies in different sources, Brigid is almost universally described as the Dagda’s child.

Many gods were also named as the Dagda’s sons. These included Midir, Aegnus, Cermait, and Aed.

Although Celtic legends often given varying stories for the parentage of the gods, the Dagda seems to have often been linked to Danu. She was a creator goddess who does not feature in any indivdual myths, making it likely that she was a primordial force rather than a human-like woman.

In some traditions, many of the Dagda’s children are born to Danu. In others, he and his brother are themselves children of this original mother goddess.

If the Dagda was a husband of Danu, their union would be one of two fertility deities. As she is often considered to be the mother of all the Tuatha de Dannan, who bear her name, he would be the father of all.

This tradition may explain why so many prominent figures in Irish mythology have familial links to the Dagda. Although his story may have changed over time, his origins might have been as the pantheon’s creator god.

This belief is preserved in one of the names gven to him, Eaochaid Ollathair. Ollathair, life the title given to Odin and other chief gods, means All-Father.

Eventually, however, the Dagda was seen as part of a broader family and lineage. He was the brother of King Nuada, the father of Brigid and Aengus, and the lover of the Morrigan.

After Nuada fell in the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, Lugh succeeded him as king. He ruled for forty years before eventually passing the throne on to the Dagda, who was High King of Ireland for eighty years before finally succumbing to the wounds he sustained at the Second Battle of Moyturra.

Bru na Boinne

The Dagda ruled from his home, Bru na Boinne. His home would play a prominent role in a well-known Irish myth.

The Dagda’s role in the story, however, differs widely depending on the source. In many he is one of the heroes of the tale, while in others he loses his home to his son.

Aengus was the Dagda’s son by Boann, a river goddess. Bru na Boinne was the estate that controlled her river valley.

According to one version of the story, Aengus was given to Midir, his older half-brother, to raise. Boann’s husband, Elcmar, was a judge of the Tuatha de Dannan and they worried he would harm the child out of anger at his wife’s affair.

When Aengus had grown, he returned to Bru na Boinne to claim his share of Elcmar’s inheritance. Although he was not the judge’s son, as his stepson he was still entitled to inherit part of his estate.

When he arrived, however, he learned that Alcmar had divided Bru na Boinne between his other children and left nothing for Aengus. The young god went to his true father to ask for assistance.

Using his wisdom, the Dagda devised a plan to trick Elcmar and his heirs out of the estate entirely.

Aengus returned and asked if he could stay at Bru na Boinne for a day and a night. Because of the way the Irish language was spoken, however, the phrase he used could either mean “a day and a night” or “day and night.”

Elcmar agreed to the request, inadvertantly giving Aengus control over Bru na Boinne “day and night,” or, in other words, for all time.

Aengus and his father lived together at Bru na Boinne for most of their lives. While Aengus had tricked Elcmar out of ownership, it also served as the Dagda’s home while he was High King of Ireland.

Another version of the story, however, claims that it was the Dagda himself who was tricked out of his home. He had given land to his other children and neglected Aengus, while Elcmar is not mentioned at all.

Most stories, however, seemto contradict this version of events.

The Dagda was associated with music and wisdom, so while Aengus was renowned in these areas it seems unlikely that he would have been tricked so easily. He is also usually described as being king in Bru na Brionne, and if the king had promised land to other powerful gods it would be unusual for all of them to give up their claim without a fight.

It is probably most accurate to interpret the Dagda and Aengus as allies in the scheme.

The Dagda as the Father

In Irish mythology, the Dagda was one of the prominent gods of the Tuatha de Dannan. The brother of their first king, Nuada, he was instrumental in helping his people win control of the island.

In the fight against the Fomorians, the Dagda used both physical strength and magic to help the Tuatha de Dannan win. He also partnered with the Morrigan, the goddess of war and death who is often said to have been his wife.

The union between these two deities represents a common theme of life and death forces being paired together. The Dagda is usually interpreted as a god of fertility, abundance, and the earth.

Many of his legends and attributes allude to this role. He has a bottomless cauldron so his people never go hungry, returned cattle to the Tuatha de Dannan after their war, and took power over the mountains and rivers before his famous battle.

His connection to fertility is also shown through his many children. Among them were well-known gods like Brigid, Midir, and Aengus, with whom he shared his home at Bru na Brionne.

He was also often connected to Danu, the primordial mother goddess for whom the Tuatha de Dannan were named. This connection may indicate that he was once seen as a similarly elusive father figure before his mythology was developed.

The Dagda was a god of life, death, fertility, and power. Most importantly, however, he was a god of order would could bring structure to men’s emotions, the seasons, and the cycle of life and death.