Greek

Argus: Hera’s Hundred-Eyed Guard

Argus: Hera’s Hundred-Eyed Guard

What better watchman than a giant with a hundred eyes? Learn the story of how Hera employed Argus Panoptes, the giant guardian of legend!

Argus was a giant in the service of Hera who was remembered for his watchfulness.

Set to watch one of Zeus’s first mortal mistresses, the giant was killed by Hermes as he served his goddess.

He was so vigilant in his duties that he was said to have one hundred eyes that allowed him to be watchful at all times. Yet, Argus was not a monster or a villain.

There is a lot more to the story of Argus Panoptes than just his role as a watchman.

From how a giant won the favor of Hera to what his myth has to say about the world of the ancient Greeks, the story of Argus is full of surprises!

The Family of Argus

Although Argus was a giant, he came from a family with far more wide-spread connections to important people and events in Greek mythology. While most giants were children of Gaia, Argus was the child of a king.

Most myths say that his father was Arestor, a ruler of the city of Argos.

His mother Mycene was also from Argos. Her father, Inachus, had founded the city after surviving the great flood that destroyed most of humanity.

Inachus had named Hera as the patroness of Argos, choosing her over Poseidon. This began the strong affiliation between his family and the goddess, who had a major temple in the city.

In mythology, Inachus is not remembered primarily for founding a city or fathering Mycene, however. His other daughter, Io, would play a much more prominent role in popular myths and come into contact with her nephew, Argus.

Mycene gave her name to another city, located less than a dozen kilometers from Argos. Mycenae was such a major center of the Greek world that the period of 1600 – 1100 BC in Greece and the surrounding Mediterranean region is referred to as the Mycenean.

A Different Type of Giant

With such parentage, Argus was very different than many of the other giants in Greek mythology.

The Gigantes were generally considered primordial children of Gaia, the mother earth. From the earliest days of Zeus’s rule they had been enemies of the gods.

Gaia had sent her giant children in an attempt to seize power from the gods of Olympus soon after Zeus took power. Most had been killed and buried in the earth where they were said to cause earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

Argus, however, was not one of these giants.

Rather than being destructive and hateful toward the gods, Argus had the makings of a hero.

In one story, he had been sent to kill the monster Echidna. The mother of many of the most terrible monsters in mythology, she was feared for preying on travellers.

Argus killed her by sneaking into her cave while she slept. In doing so, he had eliminated one of the worst threats of his time.

In another story, Argus had killed a terrible bull that had been rampaging throughout Arcadia. He also killed a villainous satyr that had been stealing livestock and threatening farmers in the same region.

These were great deeds that deserved reward. The slaying of Echidna, in particular, earned him the friendship of the gods.

For his heroic actions, and as a native of a city under her patronage, Hera took Argus into her service. He became her faithful and devoted follower.

Unfortunately, service to Hera would also be the giant’s downfall.

Argus the Watchman

The most well-known story of Argus is not the slaying or Echidna or any of his other heroic services to the gods and man. Instead, he is best remembered as a watchman.

Io, who according to some genealogies was his aunt, was a priestess of Hera in her temple at Argos. Like many beautiful maidens, she attracted the attention of Zeus.

Io did not share the attraction and was worried about what would happen if Zeus pursued her. She feared not only the god, but the anger of his wife.

Io was plagued by dreams in which Zeus attempted to seduce her.

When she confessed this to her father, he turned her out of his house. An oracle had advised him that his daughter was fated to be a consort of the god, and thus needed to be out from under her family’s protection.

Zeus quickly realized that the girl was on her own and followed her as she left the safety of Argos.

Hera, meanwhile, had been keeping an eye on her husband. She knew his predilection for beautiful young human women and had no doubts that his eye was wandering.

When she saw a single thunderstorm in the distance, her suspicions seemed confirmed. She hurried to the site in an attempt to catch her cheating husband in the act.

Zeus realized that his wife was coming and acted quickly to cover his tracks. Even the king of the gods feared his wife’s wrath if she caught him attempting to seduce another woman.

He turned Io into a white cow in the hopes of deflecting Hera’s suspicions. He feigned innocence when she found him in the forest with the animal.

The goddess was not convinced, though. She claimed to have taken a liking to the heifer and asked her husband if she could have it as a token of his love.

Zeus had no choice but to hand Io over to his wife. To refuse would be proof that he was hiding something, and both he and Io would suffer the consequences.

Hera took the white cow back to her temple and summoned her faithful servant, Argus.

She commanded Argus to watch over Io day and night, suspecting some trick on Zeus’s part. Although Io appeared to be a simple cow, Hera knew her husband’s talent for shapeshifting.

Argus followed his mistress’s commands and kept a close eye on the heifer. Io could do nothing to protest her innocence.

By day he let her graze, but when the sun sank down beneath the earth he stabled her and tied–for shame!–a halter round her neck. She browsed on leaves of trees and bitter weeds, and for her bed, poor thing, lay on the ground, not always grassy, and drank the muddy streams; and when, to plead with Argus, she would try to stretch her arms, she had no arms to stretch. Would she complain, a moo came from her throat, a startling sound . . . [Io revealed herself to her father and sisters but] as they thus grieved, Argus, star-eyed, drove off daughter from father, hurrying her away to distant pastures. Then himself, afar, high on a mountain top sat sentinel to keep his scrutiny on every side.

-Ovid, Metamorphoses 1. 624 ff (trans. Melville)

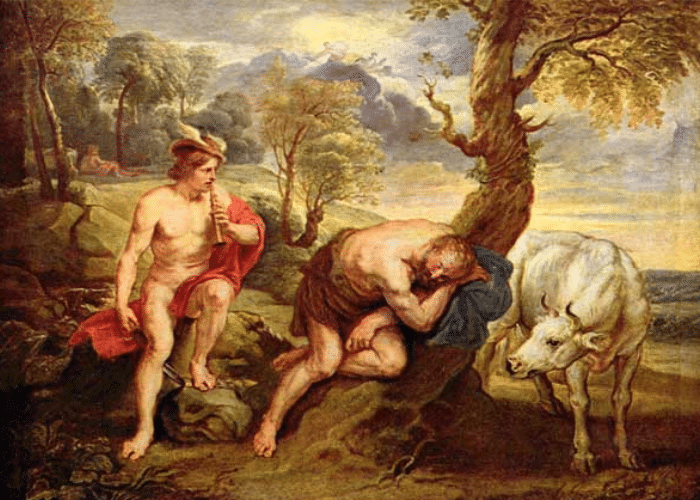

Zeus could hear Io’s plaintive mooing and resolved to rescue her from her captivity.

He summoned Hermes, his son and herald, and asked for assistance in freeing Io.

Hermes disguised himself as a shepherd to avoid attracting the giant’s attention. He went to the temple at night, when he knew Hera would not be there to spot him.

He did not go unarmed, though. While he had left his signature winged helmet and sandals behind, he carried a wand that had the power to induce sleep.

Hermes played his reed pipes as he approached the temple. Believing him to be a simple shepherd, Argus invited him to keep him company.

Hermes lulled Argus with his playing as he told stories about the invention of his instrument and the exploits of the gods. When Argus became drowsy from the music, Hermes pulled out his wand.

With a simple wave of his magic wand, the god put the giant into a deep sleep.

From there, Ovid said he pulled out a sword he had hidden in his robes and struck off the giant’s head. Other accounts said that he hit Argus with a rock to kill him.

The death of Argus was the first blood spilled among the new gods of Olympus.

The guard dispatched, Zeus freed Io and took her away from Hera’s temple.

When the goddess came the next day, she found her prisoner gone and her guard murdered. Her suspicions about the heifer were confirmed.

She sent a gadfly to torment Io, who was still in the form of a cow. Zeus’s would-be mistress wandered the entire world attempting to escape both the fly’s stings and the god’s affections.

In some versions of the story, the gadfly that Hera sent after Io was not a simple insect. It was the ghost of Argus himself, ordered even after death to make sure Io did not escape.

Io crossed the sea, named the Ionian after her, and reached Egypt. Only then did she relent to Zeus in order to be returned to her human form and escape the gadfly’s torment.

Despite Hera’s best efforts, Io became Zeus’s mistress. Their descendants included many famous names in Greek mythology, including Zeus’s other sons Perseus and Heracles.

The Power of a City

The Argus named in the story of Io became known as Argus Panoptes, or All-Eyes.

The epithet was important to distinguish him from the many other characters named Argus in various myths. These included:

- Argus the son of Zeus and Niobe. He was a king of Argos, which was named for him, and possibly the uncle of Argus Panoptes.

- His grandson, the brother of King Triopes.

- Argus who built the Argo, the ship of the hero Jason. In some versions of the myth he is also a son of Arestor.

- A son of Megapenthes, the king who traded lands with Perseus.

- The grandfather of Hymenaeus, a boy who was loved by Apollo.

- One of the sons of Jason and Medea.

- A son of Pan and one of the panes that joined Dionysus in his war in India.

- Two of the warriors in the story of Seven Against Thebes. An Argus on each side of the battle was killed.

- Dogs belonging to both Odysseus and Actaeon.

It is no coincidence that so many characters in Greek mythology share this name.

The name Argus is related to the city of Argos. One of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, Argos was a center of culture and economy in Bronze Age Greece.

Located on a fertile plain, known as Argolis, the site had been inhabited for over 6,000 years before Homer wrote his poems. The Greeks had no way of knowing exactly how old the city was, but their oral history preserved the idea that Argos had been an important place long before their own times.

In Homer’s time, Argos was one of the greatest powers in the region. It was even strong enough to challenge nearby Sparta for dominance over Eastern Greece.

The power of Argos began to wain in the Classical Era. The city was largely shunned by the other Greek powers for remaining neutral in their fight against Persia.

But this time, the 5th century BC, the foundations had already been laid for many of the myths. While Argos was less powerful than it had once been, the stories still reflected an earlier time when it had been one of the most influential city-states in Greece.

The repetition of the name in mythology is a reflection of this power.

Many of the characters named Argus traced their lineage back to the first king of that name. As the legendary founder of a great city, his name lent authority and legitimacy to his descendants for many generations.

The name also tied characters back to that power even if they were unrelated. The name itself carried the prestige and strength of the city, even when a man was not from its ruling family.

The legend of Argus Panoptes, in particular, shows the ways in which the city was reflected in those named for it. The giant’s watchfulness could be an allegorical reference to the involvement of this city he’s from in the affairs of the Greek world.

The legends about Argus before he entered Hera’s service show the role his city played in the ancient world. Both the satyr he was said to have killed and the bull he defeated had threatened Arcadia, the region in which Athens lies.

Often, myths such as these contained clues about the actual history of the distant past. As one of Greece’s strongest Bronze Age regions, it is likely that the city of Argos had defended Athens in the past.

The bull, for example, was usually associated with Crete and the ancient Minoan civilization there. Both other myths, such as that of Theseus and the Minotaur, and archaeology point to the Minoans having conquered Arcadia in the Bronze Age.

The story of Argus slaying the bull in Arcadia could allude to Argive troops defeating Minoans there in the distant past.

The Argus of mythology, along with the many others who shared his name, was a symbol of one of Greece’s greatest city-states. Although its political and military influence waned through the ages, Argos was remembered in the myths as a metaphorical giant who oversaw everything that happened in the world of the ancient Greeks.

Hundred-Eyed Argus

The watchfulness of Argus became his defining trait. He was described by writers as Panoptes, all eyes, for the close guard he kept over the heifer Io.

Argus was not the only figure in Greek mythology to receive this epithet.

Helios was called Panoptes because from his position in the sky he could see everything that happened on the world below him. As the all-knowing king of the gods and as the deity of the sky, Zeus too was sometimes called by this name.

But Argus remained the figure most closely associated with the epithet, and the one whose image would be most affected by it.

While the Archaic Greeks used “all eyes,” to mean all-seeing or omnipotent, later writers had a tendency to be more literal.

Some early versions of the story, such as that found in a fragment of Hesiod, claim that Argus had four eyes so that he could see in all directions at once. Writers in the Classical period and later, however, took the idea of the Panoptes to even further extremes.

Taking the name literally, they interpreted it as meaning that Argus was literally covered in eyes. Soon, it was common to describe the giant as having one hundred eyes covering his body.

Because only a few of these eyes slept at any given time, he was able to keep watch over Io day and night.

When Hermes lulled him to sleep, according to these accounts, it was by getting one eye to close at a time until they were all at rest.

The description of Argus as a hundred-eyed giant lived on in written mythology, although artists widely avoided depicting the grotesque spectacle of a monster with eyes covering his frame.

The Giant Commemorated

The literal interpretation of Argus has having a hundred eyes gave rise to another later addition to the story – his commemoration by Hera.

In the early versions of the myth, Argus is killed outright. Some made his spirit the gadfly that chased Io, but when she resumes her human form the fly simply fades out of the story.

It was common, however, for the gods to eternally commemorate those they loved or who had done them a great service. Often this was as a constellation, but it was also done through plants, animals, or landmarks.

Thus, Hera commemorated Argus. She placed his hundred eyes in the tail of the peacock so they would be remembered forever.

This part of the tale is an obvious later edition. Peacocks, native to Asia, would have been unknown to the tellers of the earliest forms of the story.

By the time the Greeks had regular contact with the people of Persia and India, however, the idea of the hundred-eyed Argus had become a standard part of the story. Because the spots on a peacock’s tail reminded people of several eyes, they embellished an existing myth to explain the appearance of a noteworthy new animal.

This was not unusual for the Greeks. Many stories were added to the existing mythology to tie foreign cultures and features into their world.

Increased contact with Egypt, for example, led a story of the gods seeking refuge there that made the gods of Egypt into aspects of the Greek pantheon. After Alexander the Great reached India, the story of Dionysus waging war on the people there developed.

In the later periods of Greek culture, then, the peacock was brought into Greek mythology as a tribute to Argus. The bird became a symbol of Hera, who had adorned it to honor a faithful servant.

Watched By the Eyes of Argus

The watchfulness of Argus became so central to his myth that it entered into the everyday speech of the Greek people. To be watched or followed by the eyes of Argus was a way of saying that a person was under intense, endless scrutiny.

But there was a lot more to the story of Argus than just his final duty.

He wasn’t always a hundred-eyed watchman. Even in the ancient world, many people seemed to forget that he had also killed one of the world’s most dangerous monsters and saved Arcadia from multiple dangers.

Like the city he was associated with, the strength and heroism of Argus faded over time. He was rarely mentioned as a great fighter or saviour.

Argolis had once been a powerful region but, like the giant, by the Classical Era it had been largely reduced to watching the more powerful cities of Athens, Sparta, and Corinth.

Argus Panoptes is remembered most as a watcher, so associated with a single task that he became grotesque to accomplish it. But the whole story of the giant reveals more about both him and Greek history than just his involvement with one of Zeus’s affairs.