Egyptian

Anubis: The Egyptian God of the Dead

Anubis: The Egyptian God of the Dead

The Egyptians had many gods of death and the Underworld. One of the most iconic, Anubis, was also a god whose role changed constantly over the thousands of years of Egypt’s history.

Anubis, the jackal-headed Egyptian god, is often referred to simply as the god of the dead. While he certainly was associated with death and the Underworld, his role was far more complex than this epithet might suggest.

In fact, Anubis’s specific role was constantly evolving in Egyptian religion. Was his earliest duty was as a ruler and protector of the dead, changing priorities in the culture soon gave him a much more specialized role.

Anubis is most well-known today not as a general death god, but as the god of mummification. In making the first royal mummy, he became the expert on preserving the dead so they could reach the afterlife in nearly pristine condition.

Without Anubis’s services and protection, souls would be forever trapped in the space between life and death. How he got this role and how it fit into the broader beliefs of ancient Egypt is a story that spans over three thousand years of recorded history.

The Early Origins of Anubis

Archaeological evidence shows that Anubis was probably one of the first recognizable gods to emerge in Early Dynastic Egypt.

This period, from roughly 3100 to 2686 BC, marked the beginnings of a culture that would thrive for over three thousand years.

Carvings from the First Dynasty show a jackal-headed god that is almost definitely the precursor to Anubis. In Egypt, it can be said with near certainty that these early images of jackals were linked to death.

Evidence has shown that even before the First Dynasty, jackals were associated with the dead.

Pre-dynastic Egyptians buried their dead in relatively shallow graves on the edge of the desert. There, they were easy targets for scavengers, including wild canines.

Egyptian culture, however, believed that a problem was best fought by the very force that caused it. Thus, the best protector for the dead was one in the image of the animals that scavenged off their remains.

Images of the jackal god as a protector of the dead, therefore, can be found early in Egyptian culture.

By the time of the Greeks, this god was known in the local language as Anpu. It was written in the Greek phonetic alphabet as Anubis.

The jackal-headed god existed throughout the three millennia of Egyptian culture, meaning that he took on different roles and meanings over time.

In the Old Dynasty, he was regarded as the primary god of death and the dead. Evidence from images of the time shows that he was thought of as the ruler of the Underworld and the primary guardian of the dead.

This would not last, however. Like most gods, thousands of years of subtle change left Anubis recognizable but with a significantly different role and mythology than he would have had in Egypt’s earliest history.

The God of Embalmers

As the cult of Osiris grew more central in Egyptian religion, the kingly god came to be revered as the ruler of the Underworld.

Anubis’s role as the god of the dead was changed, therefore. His story was changed to be a part of the new mythology that placed Osiris and Isis in central roles.

Osiris was murdered by his brother, Set, who then usurped his position as king. To keep Osiris from going to the Underworld, Set cut his body into pieces and hid them throughout Egypt.

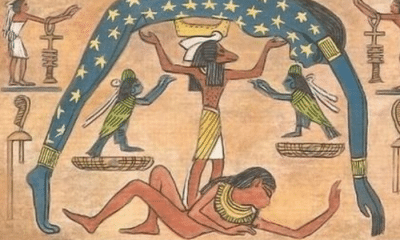

Isis and her sister, Nephthys, spent years searching for her husband’s remains. Until they were brought together, Osiris’s soul would never be able to pass on.

When they had gathered all the pieces, they took the body to Anubis to be prepared for burial. The jackal god had experience in dealing with the dead, but would have to make special preparations for the body of the god-king.

Anubis prepared herbs and magical incantations to prevent the body from decaying. Working with Thoth, the god of scribes and knowledge, they kept Osiris’s body in a state almost indistinguishable from life.

They did such a masterful job that Isis was able to temporarily reanimate her husband’s body and conceive a son, Horus, to someday challenge Set as the rightful heir.

Horus eventually retook the throne, but Osiris’s body still could not be put to rest. His heir had to construct a fitting tomb to allow the could to travel safely to the Underworld.

While the tomb was still under construction, Set continued to threaten his dead brother’s legacy. He tried several times to steal the body and destroy it to prevent Osiris from ever ruling over the Underworld.

Three times, Set attempted to get past the guards that Anubis assigned to protect the corpse. Twice, he tried to sneak into the embalmer’s shop in the guise of Anubis himself.

On the one occasion that Set succeeded in stealing the body, Anubis gave chase. He ran Set down in the desert and took back the corpse, imprisoning Osiris’s wicked brother until Osiris was safe in the Underworld.

When Set escaped, however, Anubis killed him to ensure that the god was never threatened again. Anubis burned his body and killed all of Set’s followers, finally ridding Egypt of the usurper’s forces forever.

The episode not only incorporated Anubis into the new death cult of Osiris, but it also gave him a new role in Egyptian culture.

Anubis became the god of embalmers and, as the practice grew, mummification. He was the patron of those who prepared bodies for the journey into the afterlife, a practice that was both a physical task and a religious ritual.

He also maintained his position as the guardian of the dead, although it took on a new meaning. Rather than watching over those who were already in the Underworld, Anubis protected those who were still being prepared to make the journey.

Many Egyptian tombs, therefore, included prays to Anubis carved around their doorways and in the interior. It was hoped that these prayers on behalf of the dead would not only protect the soul on its journey to the afterlife, but also protect the tomb from being looted and damaged.

The Birth and Abandonment of Anubis

One of the stories about Anubis that changed significantly was how he came to be.

On the whole, Egyptian religion seems to place relatively little emphasis on the origins of their gods. Unless succession was an issue, as with Osirus and Horus, these stores varied widely over time.

They also varied by region. Local cults gave the gods origins linked to their centers of worship, creating many competing traditions throughout the Nile Valley.

Initially, Anubis was the most powerful son of Ra. The sun god, who later became powerful in the Underworld, was the preeminent deity of the early Egyptian dynasties.

Eventually, however, another of Ra’s sons became more widely-revered throughout Egypt. Osiris became not only the archetype for kingship, but also a god of both life and death.

By 2000 BC Anubis’s birth story had been changed to reflect the fact that he was now far less powerful than Osiris. The story that emerged at this time is the most well-known and detailed story of his birth and continued to be told as late as the 1st century AD when Plutarch recorded his thoughts on Egyptian mythology.

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

-Plutarch, Isis and Osiris

In this version of the myth, it is strongly implied that Set and Nephthys were married just as Osiris and Isis were. While this is often suggested, a relationship between them is never made clear.

This myth made Anubis the older half-brother of Horus. Because Osiris and Nephthys were not married to one another, however, Anubis did not threaten Horus’s position as heir.

In an alternative version of this story, Anubis was actually the son of Set instead of Osiris. When Horus, Osiris’s son with Isis, regained the throne from his uncle, Anubis accepted his authority and lived peaceably under his rule.

As time went on, the origin stories of Anubis and the other gods became more varied instead of less. Alternative myths named him as a son of the cat goddess Bastet, a true son of Isis, or, in the Greco-Roman era, an alternative version of Hermes.

Epithets for the Jackel

With the many roles he played over the long history of Egyptian mythology, Anubis also came to be known by many titles and epithets.

Many of these are recorded in other languages, allowing us to clearly decipher the poetic language and noble titles given to the embalmer god.

Others, written only the hieroglyphics, can be discerned through our knowledge of that system. By comparing them to other phrases and titles written pictographically, scholars can decipher their meaning even if the spoken language is unknown.

Names for Anubis often referred to the West, where the setting sun was supposed to mark the path to the land o the dead. Others recalled the practices of embalming and mummification.

Titles and epithets for Anubis included:

- The Lord of Mummy Wrapping

- First of the Westerners

- Child of the Western Highlands

- Chief of the Necropolis

- Counter of Hearts

- Master of Secrets

- Lord of the Sacred Land

- Prince of the Court of Justice

- The One Who Eats His Father

- He Who is in the Place of Embalming

- The Dog Who Swallows Millions

The reference to Anubis as One Who Eats His Father recalls both his role as a scavenger and a grisly aspect of the mummification process. Some records said that embalmers ate small pieces of the body’s internal organs in a remembrance ritual, perhaps inspired by the scavenger origins of their patron god.

Anubis the Psychopomp

Many of the god’s names also reference his role within the Underworld itself.

When Anubis no longer ruled over the dead, he became an important figure in guiding the souls of the dead into the next world. He took on the role of a psychopomp who both travelled with the dead and protected them on their journey.

The Book of the Dead and other records specify the role Anubis played in guiding the dead.

One of his major roles was as the “Guardian of the Scales” that weighed the hearts of the dead against a feather from the wings of Ma’at, the goddess of truth.

Anubis led each soul to a set of scales that would weigh the person’s heart. A light heart meant that the person was untroubled so they would be allowed to continue on the path, but a heart that was heavy with crimes and evil deeds could not move on through the afterlife.

Those souls would be fed to Ammit, a terrifying chimera monster and be destroyed forever.

In this task, like embalming, Anubis was aided by Thoth. The ibis-headed scribe recorded the results of each weighing and constantly checked the scales for accuracy.

In later eras, Anubis’s role as the guide of the dead led Greek visitors to liken him to their own psychopomp, Hermes. Seeing the animal-headed gods of Egypt as bizarre and primitive, the Greeks jokingly referred to Anubis as “Barker” or simply “The Dog.”

Identifying the Canine

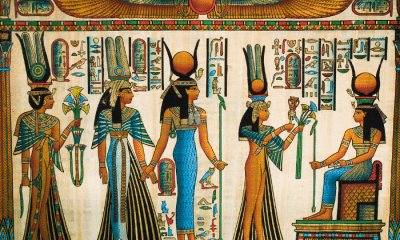

Like most Egyptian gods, the iconography associated with Anubis changed very little over the thousands of years of Egyptian history.

He was depicted with the head of a jackal in all of his images, and generally with its tail as well. His head and often body were black, a color long associated with death.

The most notable change in the long history of his iconography was the way in which his name was written in hieroglyphics.

In early history, the sound signs that composed his name were followed by an icon of the jackal-headed god with a human body sitting with his knees pulled up. By the late Old Kingdom, this had changed to a full jackal sitting on a tall stand.

The image of Anubis was so consistent that it seems as though there is little that can be discovered about it. Recent research in the field of Biology, however, has changed the way we look at this five-thousand-year-old image.

Anubis is associated with the golden jackal, a species native to the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent. Usually seen as scavengers, these canids usually hunt alone or in pairs at dusk and dawn.

In 2015, however, genetic research showed that we have been calling Anubis by the wrong name for hundreds of years.

The golden jackal is, in fact, more closely related to the wolves of Europe and Asia than it is to the other jackals in sub-Saharan Africa. The species has been renamed the African golden wolf in light of this discovery.

Therefore, while Anubis has been referred to as a jackal-headed god in scholarship and popular culture for many years, he actually has the head of a wolf.

This distinction does not change the fundamental mythology or meaning of the god and would have had no impact on the way ancient Egyptians viewed him. For modern readers, however, it helps to illustrate the fact that even the most commonly-accepted truths about ancient Egyptian culture can always be changed in light of new scholarship.

Anubis as the Protector of the Dead

The jackal-headed god Anubis was associated with death from the earliest days of Egyptian culture. Made in the form of the wild wolves who scavenged fresh burials, he was thought to be the best protection from the forces that threatened the dead.

The earliest form of Anubis was as a protector of graves and a major figure in the pantheon of the Underworld. As the cult of Osiris gained power, however, Anubis’s role would change.

Osiris became the king of the Underworld and Anubis was recast as the god, possibly his son, who helped him on the way. He preserved and protected the body so that Osiris could reach the afterlife safely, becoming the patron of embalmers and the creator of mummification.

While Anubis continued in his protective role, his work became more tangible. The embalmers who prepared Egypt’s dead saw him as their forefather and tombs bore inscriptions praying for Anubis to care for the bodies within.

By the Greek era, the god’s role had expanded to that of a psychopomp. He escorted souls through the gate between life and death and weighed their hearts to determine who was worthy to move on.

Anubis’s image remained static and consistent throughout Egyptian history, as was common in that culture’s art and writing, but his story changed significantly. Anubis shows modern readers that the ancient Egyptian religion was far more changeable than the culture’s overall continuity might suggest.